As an act of defiance against the pattern he has been anchored to, this impulse also plays like an obligatory death sentence. Yet the movie isn’t concerned with any of the details of such a bleak nightmare, even as the periphery of his observations is molded by them. For nearly two hours, the lens stares firmly in the direction of Saul Ausländer without blinking, as it obscures what goes on around him in order to focus entirely on how a face watches, deals and briefly shows emotion in the face of relentless violence. That disruption is caused early on, following a prologue in which loud voices thunder through an urgent gathering of prisoners and officers. Saul’s figure is shown marching silently through crowds as if sleepwalking through a fog. The nearby dialogue is insistent, and not without some level of cruel irony: “Undress now. Remember your hook number. Shower now before the soup gets cold.” On the other side of the door is a chamber that will ultimately become their tomb, and after the doors slam shut, Saul’s emaciated face stiffens into stony ambivalence, even as those on the other side bang against the metal frame in cries of horror. Then, when the Germans demand that he and his fellow workers clear the chamber of bodies, he discovers a young boy who survived the ordeal, possessing him to nurture the child in his last minutes before burying him with some level of dignity.

The underlying narrative structure – recalling Tim Blake Nelson’s “The Grey Zone” – is familiar lore to all those versed in the histories of the holocaust: within the walls of Auschwitz, a group of Jews (known as the “Sonderkomando”) are offered a short reprieve from death in exchange for their assistance in directing waves of prisoners towards the gas chambers, all before disposing of their bodies in ovens and mass burial sites. Then, as the pattern reaches the peak of its grotesque monotony, two key events transpire: 1) a child survives the gassing, inspiring false hopes of miracles, and 2) an uprising within the crematoriums builds to a climactic showdown between prisoners and soldiers. Understanding the framework of this reality is not necessary in dealing with the reality of “Son of Saul,” but having it as an added facet of awareness certainly anchors the perspective of our observations. As these realities ebb and flow through the hushed determination of the Sonderkomando, Saul’s obsession with the boy takes him beyond the reality of merciless Nazi occupation and right into the dying heart of a group of Jewish survivors; when he begins asking around for a Rabbi to assist in a burial, a peer coldly retorts: “why, isn’t the one at the stove good enough?”

There is a challenge in dealing with such a premise on some level as a moviegoer. Though it is consistent with our perceptions to see how people can be made to suffer in the hands of oppressors, it is far more ambiguous to accept the manipulation of a scenario where the persecuted can be forced to participate in the slaughter of their own culture. But those are realities we must face for the sake of the historical context, otherwise we simply spin in the loop of our reservations. “The Grey Zone” dealt with these in the milieu of a story swirling in intrigue and strategy, and did not flinch in the face of its paralyzing hopelessness. While “Son of Saul” knows the inevitability of how this all must play out, it places the burden of a response entirely in the hands of one person, a face we come to depend on as a single point of possibility in a world that wants to turn him into a statistic. That gives his dogged pursuit an air of admiration more than it does one of sickness. Others resolved to their fates feel the burden of Saul’s choices, but when there are so few ones to make to begin with, who can indeed begrudge him the chance to act on a feeling of responsibility, however delusional?

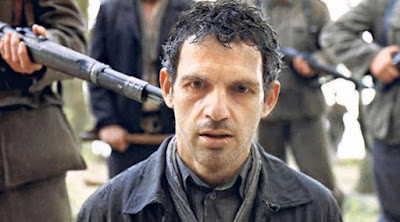

The dramatic edge of the film is almost suffocating in its sincere delivery. For Géza Röhrig, the man who plays Saul, this isn’t a mere performance by an actor – it is the personification of one’s profound humility, recalling the simplistic endurance of Maria Falconetti in “The Passion of Joan of Arc.” How did Nemes draw such subliminal vigor out of such a relatively new face? A sense that the material could rouse most gifted actors into the upper tiers of overzealousness is not too inaccurate a description; in most hands, all of this could have come across as implausible, lacking the intensity of restraint. If Röhrig possesses a quality above most possible candidates, it’s that his solemn demeanor helps to emphasize the weathered features of his face. This isn’t just a collection of blank stares or pursed lips dominating the view of the camera; there are abundant nuances across a plethora of tense plot points, and the face transitions between all of the obligatory reactions so seamlessly that we are glued to the gaze with the utmost curiosity, never sure about what will come next as the events grow darker with each passing minute.

The audacity of the director’s technical choices is rare, but sound. Like Bergman, he sees the face of his subject as the only means in connecting with the feeling of such an indescribable event. Like Carl Dreyer, he is content to build an elaborate production without catching much of it in camera view; there are few establishing shots and even fewer pull-backs to perspective, because they are irrelevant to him and his protagonist. What’s most remarkable about that approach, perhaps, comes down to the assuredness of his intention. Wouldn’t most movies dealing with this subject matter be tempted to pan back for more insight? Wouldn’t they be all too eager to emphasize the details, or create actual victims and villains out of the shouting figures in the backdrop? To him, anyone seeing the film already knows what atrocities are occurring behind Saul’s shoulders. If there is something about the holocaust that is destined to be lost as time marches on, it has little to do with facts and more to do with instinct. There is a scene towards the end so heartbreaking in this realization that it left me swelled in tears: as the Sonderkomando rush to escape the camp, the camera follows Saul as he attempts to bury the boy on a hill, using his only available tool – his hands – to pull soil away from the Earth. How sobering to consider what people will do to retain what little shred of humanity they clutch beneath the deadened exteriors.

Dozens of films have been made about the tragedies of war. Passable ones can shed light on events that seem foreign or inconclusive. Good ones bring us closer to understanding the undercurrents that went into them. But great ones, I think, are those that don’t bother with the formality of cinematic pacing or formula; they are created out of a need in others to build our emotional awareness, hopefully for the sake of expanding our compassion beyond the limits of motion picture escapism. Of those that deal directly with the casualties of Nazi Germany, few – other than “Shoah” (a documentary) or “The Pianist” or “Schindler's List” (dramatizations) – have left us in such silent contemplation of human cruelty. “Son of Saul” easily joins their company. It is a modern masterpiece, full of awe and pathos, and justly sworn to a cause that reveals more about ourselves than we might be willing to deal with in isolation.

Written by DAVID KEYES

Drama/War (Hungary); 2015; Rated R; Running Time: 107 Minutes

Cast:

Géza Röhrig: Saul Ausländer

Levente Molnár: Abraham Warszawski

Urs Rechn: Oberkapo Biederman

Todd Charmont: The Rabbi

Produced by Krisztina Pintér, Gábor Rajna, Gábor Sipos, Judit Stalter and Robert Vamos; Directed by László Nemes; Written by László Nemes and Clara Royer

No comments:

Post a Comment