"Beyond the Sea" maintains the same indirect tradition seen earlier this year in "De Lovely," in which a famous talent seems to stand off in the shadows while his memories manifest in the form of a stage musical. In what can essentially be described as a "This is Your Life" technique, audiences are forced to accept the impression that there are no cameras or scripts around dictating the movement of the narrative in front of them - instead, life itself wants to play out unhindered right in front of our eyes, as if the characters are playing puppeteer with their own recollections so that ordinary instances are made into glossy moments without seeming obviously recreated. Make sense? Of course it doesn't, and such an approach was certainly part of the problem with the recent Cole Porter film biography (among other things). The questions are often too great to be skipped over. What reality are these people in? Are they stuck somewhere between consciousness and dream? And how can anyone remember so vividly the fine details of their own past? The immediate dilemma facing Kevin Spacey, who both directs and stars in this biopic about singer Bobby Darin, is that his source material is required to reference the famed celebrity's untimely death. Therefore, if there is demise here, how can a persona plausibly look back at his life after the fact? What is the ground rule, exactly?

Friday, December 31, 2004

Wednesday, December 29, 2004

The Aviator / ***1/2 (2004)

Martin Scorsese's passionate love of filmmaking has no doubt made him an ideal candidate for all sorts of new cinematic challenges, and in "The Aviator" he finds himself at the helm of something particularly interesting: a story that blends familiar narrative territory with a seemingly-foreign historical context (at least to him). It is easy to understand, at least, his primary desire; after all, a good portion of his career has centered on the notion that his film's heroes are usually encumbered by enough quirks and personal dilemmas to undermine their sense of importance. As luck would have it, famed billionaire Howard Hughes was exactly that kind of individual in real life - so much so, in fact, that one almost wonders whether the director's past endeavors were just stepping stones on the way to channeling this specific persona. Drive made Hughes a figure of notoriety, no doubt, but fate brings his visage to the fingers of a craftsman whose own fame is a result of dissecting the most flawed and troublesome movie protagonists of our time. He hardly seems out of place with the familiar approach, but the facet of reality gives him a whole new playing field to explore.

Monday, December 20, 2004

National Treasure / *** (2004)

If you can call it entertaining, you're more than justified in calling it good. This, at least, is how someone like yours truly feels when it comes to "National Treasure," a sleeper hit that has endured so much critical backlash since its release in November that one almost feels guilty in disagreeing with the consensus. The audience, on the other hand, seems to have seen a different film than what the paid professionals have: an action vehicle that on one hand is very silly, and on the other is extremely effective in conveying the sheer thrill of its wacky situations (and judging by the box office success, one would also argue that it's probably worth repeat viewings). For fairness sakes (and for the basic fact that I simply enjoyed what I was seeing), I am obliged to leave all points of cynicism out of this review. Few can argue that John Turteltaub's ambitious vehicle is about as unbelievable as a film can get, but if one is able to leave all sense of logic at the door, it's also very hard not to have a darn good time in the process.

Friday, December 17, 2004

Blade Trinity / ** (2004)

"Blade: Trinity" begins with an effective sequence in which a group vampires revive the spirit of Dracula, and then slowly but surely abandons the franchise hip factor and descends into pure banal territory. One would have hoped that this trilogy would go out with a bang, but the gun winds up shooting blanks instead. And that's more of a shock than you might realize, too, because like its predecessors, the picture is engulfed by a premise so seemingly expert that it would be hard to impair its quality otherwise. The first two movies, on the other hand, knew that it took more than just a heap of action shots to shape an intriguing premise into an equally-satisfying payoff; here, director/writer David S. Goyer seems to be more amused by visual energy and less concerned with how he is going to answer crucial questions or when the plot will be allowed to think instead of react. That Goyer is the same writer of the previous "Blade" flicks as well as the brilliant "Dark City" is an issue that few will be able to get past.

Friday, December 10, 2004

Alexander / *1/2 (2004)

"Fortune favors the bold."

Judging by Oliver Stone's "Alexander," it also favors the pretentious. By far the most impressively inane blockbuster to hit the big screen all year, here is a film that reaches so high and far that it's almost a little perplexing as to why it makes such a miserable thud in the end. For a new filmmaker with dreams of cinematic grandeur, such an undertaking would have died even before the footage was done being shot - but for a filmmaker like Stone, who has both made a career out of strokes of brilliance as well as periods of temporary insanity, the product creates the distinct feeling that it is being delivered just for the sake of silencing impatient investors. The director and his cast and crew of talented individuals did not so much make a movie as they made a mess; it lacks both the shape and the skill of a plausible historical epic, and the fact that its scope is so extensive leaves you feeling like a kid who is being pulled away from all the fun rides at the local carnival.

Judging by Oliver Stone's "Alexander," it also favors the pretentious. By far the most impressively inane blockbuster to hit the big screen all year, here is a film that reaches so high and far that it's almost a little perplexing as to why it makes such a miserable thud in the end. For a new filmmaker with dreams of cinematic grandeur, such an undertaking would have died even before the footage was done being shot - but for a filmmaker like Stone, who has both made a career out of strokes of brilliance as well as periods of temporary insanity, the product creates the distinct feeling that it is being delivered just for the sake of silencing impatient investors. The director and his cast and crew of talented individuals did not so much make a movie as they made a mess; it lacks both the shape and the skill of a plausible historical epic, and the fact that its scope is so extensive leaves you feeling like a kid who is being pulled away from all the fun rides at the local carnival.

Wednesday, November 17, 2004

Task of movie reviewing made much easier by absence of Jack Valenti

Just this past week, DVD screening copies of the Focus Features releases "The Door in the Floor" and "Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind" wound up on my doorstep. Their arrivals certainly weren't something to jot down on the out-of-the-ordinary note pad or anything (if you were a member of the Online Film Critics Society, you'd know full well that this happens frequently during the latter months of a year), but considering how much hysteria had been caused in the industry over the previous months regarding piracy, they were nonetheless a sight I hadn't expected to see for some time. The first emotion was that of skepticism, but then an epiphany: "Of course! That old poop Jack Valenti is no longer at the head of the table at the Motion Picture Association of America!" Remember what they used to say in those high school comedies about parents always spoiling the fun of an ambitious teenager? Imagine, then, how a party animal would feel knowing that his mom or dad has gone on an extended vacation, leaving him alone in the house.

Thursday, November 11, 2004

The Polar Express / ** (2004)

"The Polar Express" is the most expensive vanity project ever made. Fashioned out of a computerized concept, with a budget that reportedly extends into the area of $170 million, Robert Zemeckis's flashy and ambitious motion-capture holiday cartoon is so intoxicated by its own wild production values that it has little time to do anything else - not the least of which is tell a halfway-compelling story, even by the average child's standards. And that's a little disheartening, because the picture and all its positive energy arrives at a very convenient time, when the world around us in utter turmoil and there is such a strong desire for something genuinely uplifting. For those a little more intuitive than most young kids, however, it's hard to find much to celebrate in a film that seems less like a good-hearted fable and more like a successful business man waving around his bulky check book.

Friday, November 5, 2004

I, Robot / ** (2004)

Seeing the name Alex Proyas attached to any science fiction film should be an immediate assurance of greatness. What we are dealing with here is not just a specialist of his craft, but an artist and a visionary, celebrated by his peers for taking minimal concepts and developing them into something beyond expectation. Any moviegoer who was fortunate enough to get to see his "Dark City" during its brief 1998 theatrical run can vouch for this claim, as it remains perhaps the most imperative film of its genre in the last ten years (and more importantly, was seemingly responsible for providing a lot of the early ideas explored by the Wachowski brothers in "The Matrix"). Now, the very suggestion of seeing him at the helm of "I, Robot," a film inspired by the famous Isaac Asimov story of the same name, suggests that we may be in for a repeat scenario. Once a guy finds his true forte, after all, what's to stop him from going even further?

Shark Tale / ** (2004)

Ocean divers see only what their eyes permit when they descend into the deep corners of the sea, but animators come equipped with the privilege of imagination which allows them to perceive such things in both a brighter and more amusing framework. Innocent schools of fish can become civilized societies, while vibrant coral reefs can become big urban habitats. The fact that the floodgates have opened thanks to computer animation now allows these images to be pure realities - but just as innovation can breed creativity, so can it too breed repetition. Disney/Pixar's "Finding Nemo," released last year to immense commercial success, was the first computer-generated endeavor that gave personality and narrative flair to deep-sea creatures, and now we have "Shark Tale," in which the filmmakers fill the screen with the same familiar backdrops and characterizations that seem to have grown all too common by animation standards. If not for the fact that the visuals remain so colorful and distinctive, in fact, one would almost accuse the studio, Dreamworks, of being too predictable a competitor.

Saw / **1/2 (2004)

Unconventional brilliance or over-the-top fodder? These are the two answers that come to mind when one questions the achievement that is "Saw," especially as it leaps ever-so-zealously towards an ambitious climax. Up to that point, the movie's near-numbing attack on the senses has a certain zeal that is almost commendable - its approach a drastic departure from the most recent Hollywood horror films - and viewers react, just as the filmmakers hope, with a certain distress that is almost emotionally scar-inducing. But as is required of any movie with the chutzpah to challenge the conventions of value in the cinema, there must also be a certain amount of relevance in the scenario so that it emerges as something more than just a flashy geek show. Director James Wan's serial killer thriller, about a murderer whose streak of homicides makes his victims the target of their own fate, seems to provide little ground for that to happen; while its details are hardcore and gratuitous, the payoff is lackluster, and nearly all the moments in which you expect the film to pull away the mask and reveal a deeper identity end up feeling like long exercises in overkill. The fact that it is all well made on a technical level makes that assertion all the more difficult to face.

The Incredibles / **** (2004)

Pixar's "The Incredibles" is by far the best of the CGI-animated films in the Disney canon, a wondrous and exciting spectacle that is just as enticing narratively as it is visually, and a film that reaffirms the strength of the animator's imagination. It's also a considerably extreme departure from the Pixar standard, side-stepping the widely-accepted "buddy movie" approach of films like "Finding Nemo" and "Toy Story" so that it can charter new and more satirical territory - namely, a story involving a family of misfit superheroes. The leader of the pack, Mr. Incredible, is kind of like a Superman with more compatible social skills, and his partner in crime, the virtuous and fetching Elastigirl, is a headstrong woman who is perfectly capable of holding her own against a job dominated by the male ego. Together, they live by the tasks of any standard superhero formula - save the world, try to live a "normal" life, then save the world all over again - but as the movie opens, their vocation of choice is suddenly undermined by the onslaught of countless frivolous lawsuits (in one instance, Mr. Incredible saves a suicidal man but winds up injuring him in the process, thus resulting in a legal battle). With the profession now threatened, heroes worldwide turn in their masks and enroll in the Superhero Relocation Program. Their days of saving lives and correcting misdeeds, it seems, are over.

Thursday, September 30, 2004

Alien vs. Predator / * (2004)

The creature in John McTiernan's "Predator" was a hunter for sport, preying on anything and anyone with the chutzpah to put up a commendable fight, but to see "Alien vs. Predator" tell it, they were also revered as Gods by ancient Earth civilizations, and were directly responsible for teaching our ancestors how to build great structures like the pyramids. Quite remarkable, if you think about it - in one fell swoop, a screenplay not only manages to build back-story on a famous movie villain, but also solve one of the biggest mysteries of our planet's historical past. If you think that's amazing, then just imagine the surprise of several of the movie's characters, who are recruited at the beginning of the film to be the first men and women to explore the ruins of a newly-discovered multi-cultural pyramid buried beneath hundreds of feet of ice in Antarctica. Some are ecstatic, others are bewildered; but none of them, needless to say, are aware that this hidden fortress is actually an active hunting ground for the Predators themselves, who revive it every hundred years and engage in a dangerous cat-and-mouse game with humans as the puppets. How fortunate for the film to make this great discovery just as the fortress is being revived for another round of bloodshed.

Friday, September 10, 2004

Cellular / ***1/2 (2004)

Colin Farrell discovered last year in "Phone Booth" that Alexander Graham Bell's nifty little invention could be just as much a weapon in daily life as it can be a communication asset. Now comes "Cellular," in which Chris Evans plays a beach-going guy named Ryan, who answers his cell-phone and meets a woman on the other end who is in quite a predicament: she is a victim of abduction. As the recipient to this bizarre incoming call, he is naturally skeptical and contends that a practical joke is being played on him. But poor distressed Jessica (Kim Basinger) insists otherwise, going so far as to explain that her contacting a total stranger instead of law officials comes down to the fact that her only line of communication is a busted telephone with no dialing pad. The explanations are a nice touch, but not until Ryan actually hears a direct threat against her life does he finally accept the situation as legitimate. And by that point, of course, he is already so involved in the conflict that he can't simply hand it off to some random law official. Here, the cellular phone is not simply a device that assists this unlikely hero in undertaking whatever tasks are required of him; it is the one thread of hope of keeping this woman (and maybe even her whole family) alive.

Tuesday, August 31, 2004

Exorcist: The Beginning / *** (2004)

It's difficult to approach certain movies without the smallest morsel of cynicism, especially when they are undertakings with as convoluted a past as "Exorcist: The Beginning." Practically any movie news site would be happy to report that this theatrical release is actually the second complete version of a prequel to William Friedkin's immortal 1973 scare-fest, assembled from scratch by director Renny Harlin after the studio's first cut (directed by art-house filmmaker Paul Schrader) apparently wasn't even scary enough to be re-edited from scrap footage, let alone deserve a release. What Morgan Creek might not have consciously realized at the time, however, is that their decision to completely redo an existing and unreleased film was something for the cinematic history books, a resolution so excessive and tricky that it represents a case of decision-making that is simply unprecedented in its extremity. Furthermore, to simply erase one man's entire effort and replace it with another's also meant that a second film based on one premise would be a big gamble financially; unless it set box office charts on fire, the studio would actually be coping with the loss of money from not one but two films. That's good decision-making for you, I guess.

Saturday, July 31, 2004

The Village / *1/2 (2004)

For what seems like generations in M. Night Shyamalan's "The Village," a peaceful establishment of villagers has lived in complete seclusion, fearful of the idea of venturing out of their own borders and into the forests where unknown beings lurk. Their worry of the outside is underscored early on as farmers and young children feast at tables on an open meadow, and a beastly cry in the wooded hills echoes across the landscape, sending chills up and down their spines like mice waiting for a ravenous cat to pounce. No one knows exactly who they are or what they look like, but the town's elders refers to them as "those whom we do not speak of," suggesting that the outside forces may range from barbaric humans to bloodthirsty monsters. We as audience members know even less than what the characters seem to, but we share in their sense of dread; a world in which the boundaries are determined by lit torches and guard towers, after all, doesn't suggest that the outside beings are that peaceful or civilized.

Harold and Kumar Go to White Castle / ** (2004)

"Harold and Kumar Go to White Castle" is about two guys who get high on dope and decide to go to an out-of-town burger joint, only to have a series of misadventures with colorful characters along the way. There, that takes care of the plot synopsis part of this review.

I deliberately abandon the urge here to stretch narrative discussion regarding the latest Danny Leiner vehicle, because to do otherwise would be to apply more effort than what either the writers or the director employ in devising this simplistic off-the-wall vehicle. Much like "Dude, Where's My Car?", Leiner's first major outing as a filmmaker, this is the kind of endeavor that doesn't need anyone or anything to explain the fine print; all you are required to do is walk into the theater, watch 84 minutes of footage, and then exit without the slightest urge to recall anything that you just saw.

I deliberately abandon the urge here to stretch narrative discussion regarding the latest Danny Leiner vehicle, because to do otherwise would be to apply more effort than what either the writers or the director employ in devising this simplistic off-the-wall vehicle. Much like "Dude, Where's My Car?", Leiner's first major outing as a filmmaker, this is the kind of endeavor that doesn't need anyone or anything to explain the fine print; all you are required to do is walk into the theater, watch 84 minutes of footage, and then exit without the slightest urge to recall anything that you just saw.

Monday, July 26, 2004

The Chronicles of Riddick / *** (2004)

"The Chronicles of Riddick" is the best-looking science fiction movie since "Minority Report," so ambitious and outgoing on the technical scale that there are moments when the viewers are staring up at the imagery as if it were getting ready to yank them out of their seats and onto the celluloid. It is this precise merit, strangely enough, that gives the picture its only firm ground for a recommendation; strip away the distinctive and limitless production values, and what you have here is your standard superhero-in-space vehicle that surrenders great ideas to an auto-pilot narrative treatment. And that's a surprise, especially when you consider the level of enthusiasm that both on- and off-screen contributors seem to share in this material. The film's technicians see the exteriors through an eye that is reminiscent of the greats in the golden age of science fiction cinema, and the actors emerge as if they are caught up in an elaborate role-playing game that they don't want to end. A shame that the movie's script does such a notable job of undermining their work for a story that moves from one detail to the next like the most conventional Hollywood blockbuster you could imagine.

Sunday, July 25, 2004

King Arthur / ***1/2 (2004)

The opening credits of "King Arthur" suggest that the filmmakers are utilizing "recently discovered archaeological evidence" as grounds for a contemporary interpretation of the story, a claim that leaves almost as much doubt in mind as the relevance of yet another retelling of the famous legend. Let's be honest here: do we really need to see another version of this material? Consider the fact that John Boorman perfected the narrative when he did "Excalibur" all those years ago, or the notion that "The Mists of Avalon" has already successfully tweaked that perspective via a famous novel and miniseries. Director Antoine Fuqua should have known better than to insist on pursuing a project in which the appeal of the concept lacks the very basic of purposes, especially considering his mediocre past endeavors ("Tears of the Sun" and "Training Day"). But then again, to second-guess anyone who succeeds Michael Bay as the primary choice for directing a movie is likely as pointless as the premise itself.

Wednesday, July 21, 2004

Alien / **** (1979)

The ill-fated journey of the Nostromo in Ridley Scott's "Alien" is the kind of epic space excursion that avid 1970s science fiction pioneers like Steven Spielberg and George Lucas would probably discard in early script stages. On a written page, described in broad strokes, the concept lacks the potential visual dynamics of a "Star Wars" and the innovative scope of a "2001: A Space Odyssey." As a finished screenplay, it would be hard to assume the result being anything other than a carbon copy of those low-budget 1950s space exploitation sci-fi horror films that only film-crazed teens would have paid money to see. The revolution of visual effects in the late 60s and early 70s, furthermore, meant that the concept of silly B-movie space travel was no longer something that audiences would fall for. Just as Stanley Kubrick hotwired a new reality for filmmakers with "2001," the genre dominated by fearsome aliens picking off Earth's inhabitants had lost its footing.

Friday, July 2, 2004

The Day After Tomorrow / *1/2 (2004)

"The Day After Tomorrow" follows a small group of characters around as they prepare—and ultimately witness—global warming give way to a new ice age in the northern hemisphere. That the movie manages to accomplish all of this in a span of days in the story is your first clue to how unscientific the material is, but the fact that it manages to do so while allowing Los Angeles to be torn up by Tornadoes and New York be buried under a rising waterline makes it perhaps the most comedic disaster picture of all time. Is this an effective prospect? Alas, not when director Roland Emmerich and his writing partner Jeffrey Nachmanoff want the material to rise above silly escapist entertainment and be regarded as a legitimate source of information. The idea that we have politicians in this country who are using the film as a platform to discredit the Bush administration's global warming plan would probably make a better movie than what is served up here.

Dodgeball: A True Underdog Story / *** (2004)

"If you can dodge a wrench, you can dodge a ball," says an eccentric coach played by Rip Torn as he tosses tools at his team hoping that someone learns to do something other than just stand there and be hit by flying objects. A point like this is much more amusing in context with having seen it in "Dodgeball: A True Underdog Story," but in ways it serves at the ideal platform to begin this review. Why? Because Torn's dialogue plays less like instructions to inexperienced athletes and more like warnings to the audience about the convoluted logic required of such an undertaking. This is not the kind of movie you are going to see because you want comedy that is politically correct or even halfway rational, after all.

Friday, June 11, 2004

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban / ** (2004)

Despite consistent personal skepticism of the "Harry Potter" franchise over the past two years, "Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban," the third installment into the series, opened on the screen with nothing less than pure enthusiasm on part of yours truly. At a time when the movie theater has seemingly been bombarded with endless mediocrity, it is pointless to be finicky; and besides, the concept of revisiting Hogwarts and all its magical corridors promised a lot more upfront than most recent blockbusters have been willing to provide for an entire two hours. It didn't hurt matters, furthermore, that Chris Columbus, the director of the deeply-flawed first two films in the series, was only acting as a producer this time around; directing credits instead went to the very talented Alfonso Cuaron, whose highly-regarded Mexican drama "Y Tu Mama Tambien" from a couple years back has given him more than enough good reputation to ensure the "Harry Potter" legacy some kind of fresh perspective here.

Friday, June 4, 2004

Shrek 2 / ***1/2 (2004)

The big green ogre that is the heart of the "Shrek" franchise may very well be the Mickey Mouse of his generation. Whenever he steps on to the screen, before he even has the chance to utter a snide syllable, the audience is instantly drawn to him and his offbeat demeanor. Such distinctions don't happen very often in the art of movie artifice, but when they do, they are usually quite accidental. Consider Walt Disney's own timeless creation, for instance; Mickey Mouse didn't just become the studio trademark because that's the way it was supposed to happen, after all—rather, the talkative little cartoon rodent came into that honor because the viewers had never seen anything like him, and his artificial charisma left a lasting impression that was unmatched. Dreamworks, a known adversary to the Disney legacy, may have inadvertently challenged that distinction in the form of an overgrown (but lovable) swamp creature, who on occasion spouts one-liners, smiles halfheartedly and barks angry demands at those who get on his nerves. But what elevates him above the cliché of cartoon ogres and brutes is a persona that is as infectious and likable as cartoon personalities get, and the fact that the studio introduced this concept to viewers via a film that allowed him to be the primary hero only anchors that observation.

Friday, May 14, 2004

Troy / ** (2004)

Poor Orlando Bloom has never been much of an actor behind the pretty brown eyes and the chiseled physique, but if there is one thing that has always been certain in most of his movies, it's that he gets back-burnered long before the audience has a chance to catch on to his shortcomings as a dialogue reader. So is not the case with the new vehicle "Troy," however; in an ambitious motion picture that contains timeless thespians like Peter O'Toole, Brendan Gleeson and Brian Cox, the plot makes his character, a Trojan prince named Paris, one of the primary narrative centers, an action that leads to moments in which he blankly stares into the eyes of others while struggling with long-winded movie rhetoric, seemingly preoccupied with the fear that he might not be reciting lines exactly as they were written in the screenplay. The result is almost too insufferable for words, a performance so stiff and monotone that it almost makes costar Brad Pitt's own career of one-note renditions seem respectable in comparison.

I'm Not Scared / **** (2004)

Our movies have become starved for protagonists that exist outside of the shell of the conventional, and in Gabriele Salvatores' "I'm Not Scared" we see one director's attempt to nourish that prospect. Young and adventurous, Michele (Giuseppe Cristiano) is an Italian boy who dreams almost as often as he speaks, acting on impulse no matter who his critics are, often reciting lines from comic books while he ponders consequences of decisions before ultimately making them. In the Italian countryside, of course, there's only so much trouble you can get into, but when Michele wanders out of the lush wheat fields he considers a personal playground and onto a seemingly-abandoned lot, he finds himself at a position that no kid of his age should have ever had to face. The consequences of his curiosity might have been any normal child's undoing, but here they become the platform for which Michele can rise above his standard and live the stories of heroics he reads daily in his comics.

Friday, April 16, 2004

The Punisher / ***1/2 (2004)

The renewed popularity of comic book screen adaptations illustrates a promising new turnaround for the standards of cinematic blockbusters, in which conflicted heroes and multifaceted villains become primary driving forces behind substance instead of ambitious visuals that exists purely for the sake of assaulting the senses. The concept alone is an accessible one for filmmakers because comics already come prepackaged with the essentials: extensive back story, thorough character exposition, personal and moral conflicts, and landscapes that bring even the most zealous action into a relevant context. If there sometimes lies a problem in this approach, however, it's that an already-established backbone can sometimes encourage directors and writers to forget about the padding and go straight to the big explosions or the dramatic confrontations, which creates a severe sense of detachment as a result. Granted, even though some of the more cartoonish translations have still resulted in still-respectable results (consider Ang Lee's "Hulk," for instance), it takes real gusto and nerve for someone to abandon nearly all sense of adrenaline and simply concentrate on the material they are given. There lies the real virtue in watching such famous stories pop out at you on the big screen.

Kill Bill, Vol. 2 / **** (2004)

The first sight we see in "Kill Bill, Vol. 2" is Uma Thurman's the Bride gazing at the camera as she speeds down a highway, her eyes fierce with anger and her decisiveness firm. Reflecting back on the occurrences that have brought her to this point, she recalls the old "roaring and rampaging" movies about revenge from the 1970s, relating them specifically to her recent activities. "I roared," she insists. "I rampaged," she insists even more. "And when I arrive at my destination," she admits with a slight twinge in her voice, "I am going to kill Bill!" So goes the opening moments of a grand finale to the saga that began just six months before, in a movie with such a stellar quirkiness and skill in its energetic conviction that it was unlike anything we had ever seen up to that point (and indeed, it deserved its rank on my top ten list of 2003 as the #1 film of the year).

Friday, April 9, 2004

The Alamo / * (2004)

John Lee Hancock's "The Alamo" is less like a movie and more like a detached concept, 135-minutes of speed and adrenaline in which loud explosions, gunfire, personal sacrifice and the occasional long-winded speech are all stacked up to create the impression that a lot of crucial things are happening on screen when they actually aren't. What this ultimately results in is an experience that is barely worth the ink that is printed on the ticket stub. Aside from the fact that the film has no tact, shows no enthusiasm for its subject and forgets about every element of narrative at every possible interval, it lulls the viewer into this paralyzing state of madness where theater seats almost become cages. It doesn't help matters, either, that the endeavor itself is stretched much farther than the source material requires it to be. As friend and colleague Bonnie Crawford perfectly noted on the way out of a recent evening screening, "did it really take that long for the Alamo to fall?"

Games People Play: New York / ** (2004)

It's easy to write off the whole reality television fad because of its grotesque overexposure, but peeling away the immense hype reveals a concept that, for better or worse, is strong enough to serve as the center of inspiration for countless generations of imitators. The idea only seems exhausting because our networks have commercialized and exploited it beyond comprehension. Consider, for instance, the callousness of a show like "Fear Factor" or the dehumanizing tone found in a "Joe Millionaire"; why these shows have both failed and succeeded has nothing to do with the reality shell and everything to do with their content, because their material, no matter how broad, is still subject to the same criticism and/or praise that the substance of a traditional sitcom or television drama might endure. Besides, if the perception itself really did lack the required relevance that most of its critics suggest, would it have lasted this long?

Wednesday, March 31, 2004

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind / ***1/2 (2004)

When it comes to movie manipulation, Charlie Kaufman has turned what should be a shameless gimmick into something of an art form. Being referred to as the most absurd writer of your generation would be enough of an declaration to undermine the merit of even the most ambitious overachievers, but this is a guy who seems to operate on levels that are immune to criticism. That's because he is first and foremost a visionary, an eccentric but focused man who, unlike countless screenwriters who have tried (and failed) to spur thought on the grounds of extreme silliness, uses the idea of absurdity as a device rather than as a skeleton to drive a premise. Subtract the obvious offbeat details, then, and what you have underneath are generally thought-provoking but straightforward stories. Don't agree? Then take a much closer look at either "Being John Malkovich" or "Adaptation" before you settle on that conclusion.

Monday, March 15, 2004

Starsky & Hutch / **1/2 (2004)

A quick ransacking of the filmographies shared between Ben Stiller and Owen Wilson suggests that their casting in the leads of "Starsky & Hutch" is more than just an act of coincidence. Hard-hitting movie comedians who tend to flout the most absurd expectations of audiences, the two have actually appeared in five pictures together prior to this outing, a couple being fairly detached collaborations ("The Cable Guy" and "Permanent Midnight"), but others (like their most recent, "Zoolander") evoking the sentiment that they have somehow been appointed the next big comedy duo for the big screen. In any case, we seem to be heading towards the notion that their careers in this profession require a certain amount of shared dependency. There will, of course, always be projects for them that require solitude, but a thread of connection has been established that will no doubt require new stitches being added ever so often.

Secret Window / *** (2004)

Mort Rainey is not the man he used to be. Emotionally skewed by the discovery of his wife's adultery and the sequential tension that resulted in their separation, he spends most of his time locked behind the doors of a cabin in the woods, eating and sleeping and then occasionally waking up to write (or delete) a few new lines from a new short story on his laptop computer. His dog, a quiet little mutt who crashes out on a chair in the upstairs foyer, serves as the writer's only source of companionship, especially during moments when he is conscious but only semi-coherent (we gather during an early scene that this is probably the only major contact he's had with anyone in a while). It would, naturally, come as no surprise that the arrival of an outside influence would disrupt any such pattern no matter how mundane it is, but when Mort opens the door one morning and is confronted by a suspicious-looking man, he is literally yanked out of one reality and displaced into another. This, of course, is a setup he could only dream of capturing in one of his various short stories.

Monday, March 8, 2004

Hidalgo / ** (2004)

Joe Johnston's "Hidalgo" is an ambitious horse-racing vehicle in which the horse emerges as the most interesting character in the story. This announcement should not create the impression, though, that we're dealing with a creature that is either very likable or charismatic; rather, it's just that he's surrounded by human characters that in most other movies would likely be disposed of in the first 15 minutes. Starring Viggo Mortensen (of "Lord of the Rings" fame) as real-life cowboy Frank Hopkins, the movie is about the relationship between a man and steed as they travel halfway across the world to compete in a death-defying race on the barren soils of the Arabian desert. Hopkins, of course, is there only partially for the reward money—in essence, the journey is a chance for him to discover himself and realize his personal destiny. In other words, standard stuff.

Thursday, March 4, 2004

Eurotrip / zero stars (2004)

Understanding the motivation behind someone making a film like "Eurotrip" is like trying to understand one's motivation for laughing at it: in both cases, there are no reasons, but just empty excuses. The realm of comedy tends to leave more doors open than most other genres with a knack of stretching standards of taste, but if one thing remains certain in any and all types of movies, it's that no kind of positive response can be warranted to products in which audience response is but a side detail in a filmmaker's grand scheme. Jeff Schaffer, the man who directed the film we have before us, seems to be so amused by the fact that he's enforcing negative stereotypes and offending vast segments of population that he doesn't care about any legitimate element of humor. If you chuckle, it probably means that you are simply having a knee-jerk reaction to the deplorably bad taste the picture utilizes; in any other case, laughing would be a sign that you either have lost touch with reality or are just easily amused by films that lack any sense of judgment. You, my friend, are not the kind of person who should be reading this review.

Monday, March 1, 2004

Full Metal Jacket / **** (1987)

"The Marine Corps does not want robots. The Marine Corps wants killers. The Marine Corps wants to build indestructible men—men without fear."

The Toronto Globe and Mail's Jay Scott once bestowed Stanley Kubrick's "Full Metal Jacket" with the title of "greatest war film ever made," a proclamation that, even during a time when "Schindler's List" had not yet come to fruition, suggested either an act of bravery or one of lunacy on the part of the writer. Indeed, who would be brave enough to make such an announcement without knowing full well the striking power of an "Apocalypse Now" or a "Platoon" beforehand? Absolutely no one. But as odd or misinformed as the announcement might have seemed at the time (partially because Stanley Kubrick's endeavor wasn't initially seen as pure "war" film, per se), it nonetheless holds enough relevance today to be regarded as one of the most honest and forthright ways of describing the film's true power (notice the back of the DVD release quotes that exact line from Scott's critique). This is a movie about mentality and dehumanization rather than any varying degree of bloodshed, and that alone makes it more interesting (and important) than a standard war film that requires characters to shoot at enemies and duck behind obstacles in hopes of escaping injury or death.

The Toronto Globe and Mail's Jay Scott once bestowed Stanley Kubrick's "Full Metal Jacket" with the title of "greatest war film ever made," a proclamation that, even during a time when "Schindler's List" had not yet come to fruition, suggested either an act of bravery or one of lunacy on the part of the writer. Indeed, who would be brave enough to make such an announcement without knowing full well the striking power of an "Apocalypse Now" or a "Platoon" beforehand? Absolutely no one. But as odd or misinformed as the announcement might have seemed at the time (partially because Stanley Kubrick's endeavor wasn't initially seen as pure "war" film, per se), it nonetheless holds enough relevance today to be regarded as one of the most honest and forthright ways of describing the film's true power (notice the back of the DVD release quotes that exact line from Scott's critique). This is a movie about mentality and dehumanization rather than any varying degree of bloodshed, and that alone makes it more interesting (and important) than a standard war film that requires characters to shoot at enemies and duck behind obstacles in hopes of escaping injury or death.

Friday, February 27, 2004

The Big Bounce / 1/2* (2004)

Poor Elmore Leonard can't get much of a break these days. An acclaimed author and aficionado of the elaborate heist plot, he has lived to see several of his most famed novels turned into equally-lauded movies for over 30 years, of which only a small handful of them have been made recently. Though this might suggest that the lack of plausible consistency may have something to do with projects simply falling into ill-equipped hands, there is a bigger picture to consider: the fact that there are probably very few of us who can identify the elements that drive these stories beyond being just mildly amusing crime capers. Even I myself have a certain difficulty in grasping what Leonard's driving forces are; on the written page his stories move very traditionally and lack solid ideas, and yet still remain endlessly enjoyable down to the most brief dialogue exchanges. Luckily, the passage of time in the arts has at least taught us that we are free to enjoy certain things without having to analyze the specific reasons. But if we collectively as moviegoers can't even begin to identify the argument, how can we hold our modern filmmakers in a much higher regard when it comes to the same dilemma?

Broken Lizard's Club Dread / ** (2004)

It must be more than just a sign of coincidence that the brains behind "Club Dread" collectively refer to themselves as "Broken Lizard." Could that be because their movies tend to slither around like ambitious reptiles trying too hard to ignore crippling injuries? Quite possibly. Sitting through their latest endeavor, I was instantly reminded of their previous trek into movie territory, the ambitious but labored "Super Troopers"; like that film, this product has the kind of spark and energy so zealous that one can't help but notice the filmmakers simply using it as a mask to cover up obvious shortcomings. There is no problem, of course, in abandoning cynicism with any film that tries so hard to get past its problem areas, but not when the problems themselves are too consistent to be ignored. And as hard as Broken Lizard tries to pull the wool over the eyes of their audience this time, it doesn't change the fact that their picture is deprived of essential functions that would have otherwise allowed it to be a passable feature.

Monday, February 16, 2004

Artistic Possession -- The War of the "Exorcist" Prequel

Months after completing a prequel to "The Exorcist," art-house director Paul Schrader find himself stuck in a predicament -- his film, a psychological thriller that takes a big departure from the series, will probably never be seen by the general public

Every once in a while, a movie studio comes along and makes a decision regarding an upcoming project that is beyond dimwitted. Just ask director Paul Schrader, the latest witness to this trend, whose new opus will probably never be seen in major release thanks to the brains behind Morgan Creek Productions. Why, you ask? Because as we speak, all existing cuts of his endeavor are sitting on a shelf somewhere collecting dust while a completely new version of his movie is being shot. And get this: this new version uses different actors, an entirely different script and is being overseen by a completely new director, too. If this all sounds like the plot of some kind of anti-Hollywood satire, then no wonder—it is perhaps the first time in major cinema history a studio has gone to such extreme lengths to undo someone's effort because the end result didn't match what they had hoped for.

Every once in a while, a movie studio comes along and makes a decision regarding an upcoming project that is beyond dimwitted. Just ask director Paul Schrader, the latest witness to this trend, whose new opus will probably never be seen in major release thanks to the brains behind Morgan Creek Productions. Why, you ask? Because as we speak, all existing cuts of his endeavor are sitting on a shelf somewhere collecting dust while a completely new version of his movie is being shot. And get this: this new version uses different actors, an entirely different script and is being overseen by a completely new director, too. If this all sounds like the plot of some kind of anti-Hollywood satire, then no wonder—it is perhaps the first time in major cinema history a studio has gone to such extreme lengths to undo someone's effort because the end result didn't match what they had hoped for.

Sunday, February 1, 2004

The Best and Worst Films of 2003

If there's one thing more rigorous for a movie critic than sifting through piles of films trying to figure out which ones to review, it's composing lists of those select few achievements of a given year that either move us with their brilliance or scar us with their awfulness. The concept itself is restricting because there are usually far too many candidates for both sides of the quality divide for either list to be truly comprehensive. Several journalists (including myself) purposely restrict these lists to ten specific selections (with an occasional mention of those films that barely fell out of the bracket) because it allows some flexibility without stretching the selection too thin; however, particularly in the recent years, it is not uncommon for colleagues to do top 20 or even 30 best and worst lists. Whether there are even 20 or 30 movies worthy of either group in any given year is always up to speculation.

Tuesday, January 27, 2004

The Butterfly Effect / *** (2004)

The popularity of chaos theory goes way beyond being a topic of discussion between science geeks on a lazy afternoon; the very idea itself has writhed its way into the subtext of movie screenplays longer than you might realize. Though an adamant subject to penetrate no matter how thorough the knowledge, the most fundamental principle of the theory—known in several circles as the "Butterfly Effect"—is as simple enough to the average moviegoer as the concept of a moving camera. Essentially, this "effect" is a semi-scientific belief that the smallest actions can have devastating consequences (in more metaphorical terms, a Butterfly that flaps its wings in Africa can jump-start a typhoon on the other side of the planet). Now think about that idea closely for a moment and try to think of a film that operates on those levels of reasoning. Time's up—how long did it take for "Jurassic Park" to enter your head?

Swimming Pool / ***1/2 (2003)

Writers deal with major social problems on a personal level every single day, contemplating moves and reaching conclusions that carry nearly all the emotional weight of major life-altering decisions. Their dedication to the work is no easy task because it normally requires them to confront themselves on a routine basis, to see their own values as an artist before they can begin to share their work with the world around them. The more they discover, the more motivated they become, but once they have exhausted every opportunity to reveal something new about themselves, the well of knowledge runs dry. That's why the best writers of our time are those who demonstrate evolution as a person—if the goals have changed and the perspective has grown from when it originated, then the groundwork is in place. Inspiration, on the other hand, sometimes requires a certain amount of external searching, something that may or may not be an easy task for any kind of writer.

Monday, January 26, 2004

Cold Mountain / *** (2003)

If Margaret Mitchell were alive to see the continuing fascination with the Civil War in motion pictures, she might have regretted the penning of "Gone With The Wind." Her most famous and honored literary work didn't just inspire an equally-famous 5-hour film epic, after all, it also created the shell for which nearly every similarly-themed movie in the 60-odd years to follow would use as a housing unit, some so directly that they could pass off as cheap imitations. Whatever the reason behind so many filmmakers being so directly motivated by the work of one 1930s movie, however, the audience's continued fascination with the era no doubt fuels their efforts. Why? Not because moviegoers are interested in the war or its long and exhausting conflicts; likely, they are still amused by the period's amusing sense of social skill, as it typically involved, especially in the south, people communicating through clever analogies or lengthy discussions entirely spoken through the excessive use of metaphors. This is ultimately one of the major attractions to the idea of doing a Civil War film; everything else, including battle sequences, character strategy, moral conflicts and visual presentation, have all become side dishes.

Monday, January 12, 2004

The Last Samurai / **** (2003)

The word "Samurai," as emphasized a short distance into the new Edward Zwick film "The Last Samurai," means "to serve," specifically in this case to the Japanese empire in which it originated from. History tells us that this class of warriors, most of them peasants or citizens in the lower class, originated in the early 12th century and were subsequently called upon to act as a defense against powerful cartels of rebels, their style of combat appreciated so earnestly that its essence as an art form remained an active military force for more than 700 years. Alas, with the western influence reaching overseas by the late 1800s, these great protectors quickly became a dying breed, their skills replaced by industry and men in suits who thought catch phrases and barked warnings were much mightier than a sword's agility. This is most evident during a crucial scene during the middle act of Zwick's film, when Samurai ride into residential streets only to be stared at by hordes of disapproving eyes. Here, no one remembers what these men have done for their nation in the past; they are now just outsiders in the very society they tried to preserve for the last seven centuries.

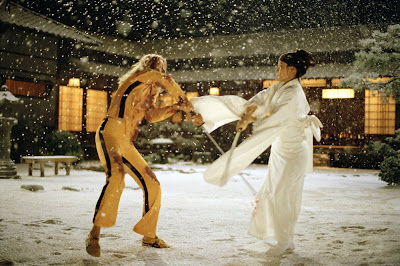

Kill Bill, Vol. 1 / **** (2003)

"Revenge is a dish better served cold."

The flutter of Quentin Tarantino's creative wings is a sight that every movie lover should see at least once in his or her lifetime, even though the opportunity only presents itself at the multiplex once or twice every decade. A master of his craft and probably the most inspired amongst his peers, he is someone who loves movies almost as much as he enjoys making them, a detail that provides him with an excellent source of groundwork in his apparent goal to satisfy as many moviegoers as possible. Consider "Pulp Fiction," his most lauded effort to date; here he harvests as many narrative and technical gimmicks as he possibly can in just two short hours, combining a modern mindset with elements of various genres of the 1970s in order to establish something more distinctive than anything done by anyone else in the industry. The movie is quirky, ironic, clever and nostalgic all in the same gulp, and the fact that it always manages to entertain without fail amongst all its style-bending and cliché-melding is further proof of how dedicated the man is to his cause.

The flutter of Quentin Tarantino's creative wings is a sight that every movie lover should see at least once in his or her lifetime, even though the opportunity only presents itself at the multiplex once or twice every decade. A master of his craft and probably the most inspired amongst his peers, he is someone who loves movies almost as much as he enjoys making them, a detail that provides him with an excellent source of groundwork in his apparent goal to satisfy as many moviegoers as possible. Consider "Pulp Fiction," his most lauded effort to date; here he harvests as many narrative and technical gimmicks as he possibly can in just two short hours, combining a modern mindset with elements of various genres of the 1970s in order to establish something more distinctive than anything done by anyone else in the industry. The movie is quirky, ironic, clever and nostalgic all in the same gulp, and the fact that it always manages to entertain without fail amongst all its style-bending and cliché-melding is further proof of how dedicated the man is to his cause.

Identity / **** (2003)

Your identity is the blueprint of your being, the foundation on which morals, ideals and opinions evolve on an internal level. Every behavioral detail is derived from its essence, and when it undergoes any kind of damage or harm, one's perception of the world around them is greatly altered. That, of course, leaves a door wide open to argument because mindsets are never similar to begin with; they are fundamental but simply not universal. And yet if that's what adds to the wondrous dimension of humanity, then no wonder it is such a studied concept in so many factions of society. Understanding our own minds is one thing, but trying to comprehend that of another, particularly someone who is much more apparently flawed, is a strangely alluring effort.

21 Grams / **** (2003)

For its perplexing first half hour, "21 Grams" exists as a series of plot splinters, fragmented and inconclusive, almost as if just a collection of outtakes from a more established product that remains unseen. But then the movie reveals itself almost as easily as it gets underway; a light switch goes on and the darkness fades away, revealing a story so stirring, so inquisitive and so uninhibited by the restraints of cinema that it absorbed me in ways that few movies ever have. You know you are dealing with something great when a plot can so easily absorb you without actually being very obvious, but it takes a stroke of pure brilliance to twist it into so many knots while keeping its viewers thoroughly engaged in the process. This isn't just one of the best movies of the year; it is one of the most thoughtful, challenging and engrossing endeavors we will ever see. Don't be fooled by anything the first 20 minutes might suggest.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)