In a genre standard where the movie camera amplifies the often disparaging final moments of human life, recent films like “The Poughkeepsie Tapes” and “Captivity” seem like nothing more than faint echoes when held against the defining catalyst that is Michael Powell’s “Peeping Tom.” Initially regarded as one of the most dangerous films ever made – and shocking enough to effectively put its famous director on the unemployment line – it came and went in the early months of 1960 with startling fallout, and the controversy it inspired continues to haunt many of those associated with it. There is a knee-jerk curiosity surrounding its existence that perplexes movie historians to this day: how did a director of fairly straightforward films find the nerve to immerse himself into the dark nature of a story like this, and without any sense of restriction? Even now, his radical shift in reasoning plays like a dual curse; young eyes eroded by the visual excess of modern times may absorb its images without grasping their initial potency, but the story’s psychological implications continue to declare themselves profoundly on our rattled cores. So many movies about the most depraved of life-takers also function as therapies for their audiences; this one makes us accessories to deplorable deeds, and rejects all opportunities to find relief from them.

Friday, October 31, 2014

Thursday, October 30, 2014

House of 1000 Corpses / *1/2 (2003)

Rob Zombie’s “House of 1000 Corpses” is a movie by a man without any sense of modulation. The camera arrives in his possession like a discovery of unprecedented importance; standing behind it, the air of his enthusiasm seems to overflow with every sharp camera angle and quick edit that emerges from his zealous fingertips. For most first-time film directors, the opportunity to take one’s bizarre visual flair and incorporate it into the frames of a motion picture would be an opportunity worthy of some level of focus, however eccentric. Alas, here is a man so enamored by the notion that creative control has been passed to him that the end result lacks a central distinction, and meanders through five or six moods with extremely disconnected results. Somewhere underneath heaps of overwrought images and flashy cuts meant to, I guess, emphasize the schizophrenic nature of his screenplay (which he also wrote), traces of a viable filmmaker are aching to connect with encouraging audiences. Those who will herald his debut effort as some sort of profound revelation will not be picking my selections during late night horror movie marathons.

Sunday, October 26, 2014

Mama / *** (2013)

Two little girls are whisked away nervously by an anxious father in the early scenes of “Mama,” and after his car crashes into an embankment during a snowstorm, they become stranded in the woods where they wander into the murky halls of an abandoned shack nestled between withering trees. No one lives there upon close inspection, but the shadows seem to vibrate with a certain existential tension – as if some kind of ominous energy remains behind, implying silent threats. Unfortunately, the ensuing actions of the rattled father cause whatever is there to manifest in the form of a chilling ghost-like figure, and when his form is consumed and the girls are left behind to fend for themselves, they make a connection with the presence that will inform their growth over the next five years. Because each is no more than a couple years old at the time of their abandonment, age passes and isolation shapes them into feral, speechless creatures that walk around on four limbs – traits that are not easily breakable once the times comes for them to be integrated back into civilization. When their whereabouts are discovered and their uncle comes rushing to their rescue, in fact, there is almost no immediate connection between them: only vague remembrances buried behind primitive survival instincts.

Saturday, October 25, 2014

Captivity / zero stars (2007)

When it comes to the daunting task of dissecting the divisive nature of film genres, no kind is more volatile than the ever-so-audacious horror movie. What is it about the dark nature of the human psyche that fills filmmakers with such polarizing ideas? What is the tipping point at which any idea can lose sight of purpose and exist purely for the sake of senseless violence and mayhem? And moreover, how can the person standing behind a movie camera effectively balance the most lurid of notions with a context that validates their ideas, no matter how graphic? The more abrasive the material, the more difficult it is for someone at the helm to discover meaning. More often than not, it all simply falls into the hands of those who lack the foresight to stay within credible boundaries, or are just too lazy to try. For every effective endeavor that does in fact emerge from this genre, there are usually ten or twenty more of a similar vein that reject the concept of moral purpose. Roland Joffé’s “Captivity,” a despicable film, is the poster child for that latter sensibility.

Wednesday, October 22, 2014

30 Days of Night / ***1/2 (2007)

A small town in Northern Alaska surrounded by 80 miles of icy wilderness is about to see the last sunrise for an entire month. Residents of Barrow board up their houses and retreat south in order to escape the paralysis of a frigid landscape, but a few dozen remain behind – as caretakers of a dormant community, or as nomads enveloped in the solitude of off-the-grid survival. On the final day of sun, a fearsome-looking wanderer (Ben Foster) descends onto them with seemingly menacing intent; his rough exterior and threatening eyes shoot fearsome glances towards innocent bystanders, and his words are indicative of that ever-so-dependable sense of foreshadowing that often accompanies eccentric strangers in the movies: “That cold ain’t the weather – that’s death approaching.” Somehow it never dawns on any of those remaining that maybe, just maybe, a month of total isolation – and complete darkness – can be an instant invitation to destructive forces, especially those fearsome nocturnal monsters better known as vampires. You can’t really fault them, I suppose; out in the middle of nowhere and so removed from social norms, are people like this really apt to be well versed in the nihilistic philosophies of horror movies?

Thursday, October 16, 2014

Alien: Resurrection / *** (1997)

Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s “Alien: Resurrection” is not traditionally viewed as being anything beyond lighthearted science fiction entertainment, but its distinctive and quirky ensemble, clearly inspired by that of Cameron’s in “Aliens,” has had its own reverb effect on more recent team-oriented action films. Contrasting the formula established by three preceding outings in this series, here is a gathering of individuals whose underlying comical sensibilities are not, in fact, defense mechanisms against impending doom; instead, they exist for the sake of adding light to a mood, a sense of cheeky awareness to a tale so clearly saturated in unending bloodshed. When some of them turn up alive (and still gleefully untarnished) by the end of the picture, a critical perception has been shattered: death no longer has to be an inevitable conclusion for all associated with this premise, even though Ripley herself fell to it at the end of the third film (and still many more are killed throughout the running time here). But is that departure in sensibility at all surprising now, so many years later, when the nature of this genre has created the elbow room of added survivors beyond the one token smart guy who lives to become a launching device for sequels?

Monday, October 13, 2014

The Poughkeepsie Tapes / ** (2007)

Moviegoers who spend any length of time with “The Poughkeepsie Tapes” are not acting as mere viewers – they are eyewitness to the inner workings of a very loathsome madman. His identity remains a mystery to all those who have followed his trail for the better part of a decade, but their endless search for answers have yielded one of the most haunting discoveries in the history of criminal forensics: hundreds of video tapes in which the actual killer, acting as director, documents his spree of horrific mayhem. When the movie opens, this critical finding also comes equipped with an extensive arsenal of unanswered questions: how did a single human being brutally massacre so many people in upstate New York for such a lengthy period of time without getting caught? Who was he, and what drove his incessant pursuit for blood? And most importantly, what does his depravity reveal now in hindsight after hundreds of hours of footage reveal the nature of his insanity – a horrific portrait of a single person, or our collective ignorance in being able to stop his reign of terror? Just as the camera once served as a window into his menacing tendencies, now it is a confessional for legal authorities and relatives who must bargain with it in some unwavering hope to fathom – and even find peace with – the fallout.

Sunday, October 12, 2014

Burnt Offerings / ** (1976)

“Burnt Offerings” is one of those all-too-familiar movie detours through the doldrums of horror mediocrity, a film about a family of would-be caretakers who decide to leave behind the bright lights of the big city and spend the remains of their summer in the comforts of a charming countryside mansion that is being rented to them by, we gather, rather suspicious owners. Because they proceed to live in said property without the slightest awareness in the conventions of basic movie composition, that presents immediate disconnect in creating a relatable experience. What people in their right minds would so eagerly agree to submit themselves to such a shady arrangement given the nature of the scenario, which involves two elderly – and rather creepy – homeowners who insist on leaving their mother behind in an upstairs bedroom for the caretakers to look after? Did it not strike a mental chord in any of them that a cheap price tag for such a stunning mansion might involve rather ominous drawbacks? Even little kids would howl with pessimism at this kind of nearsighted narrative entrapment.

Wednesday, October 8, 2014

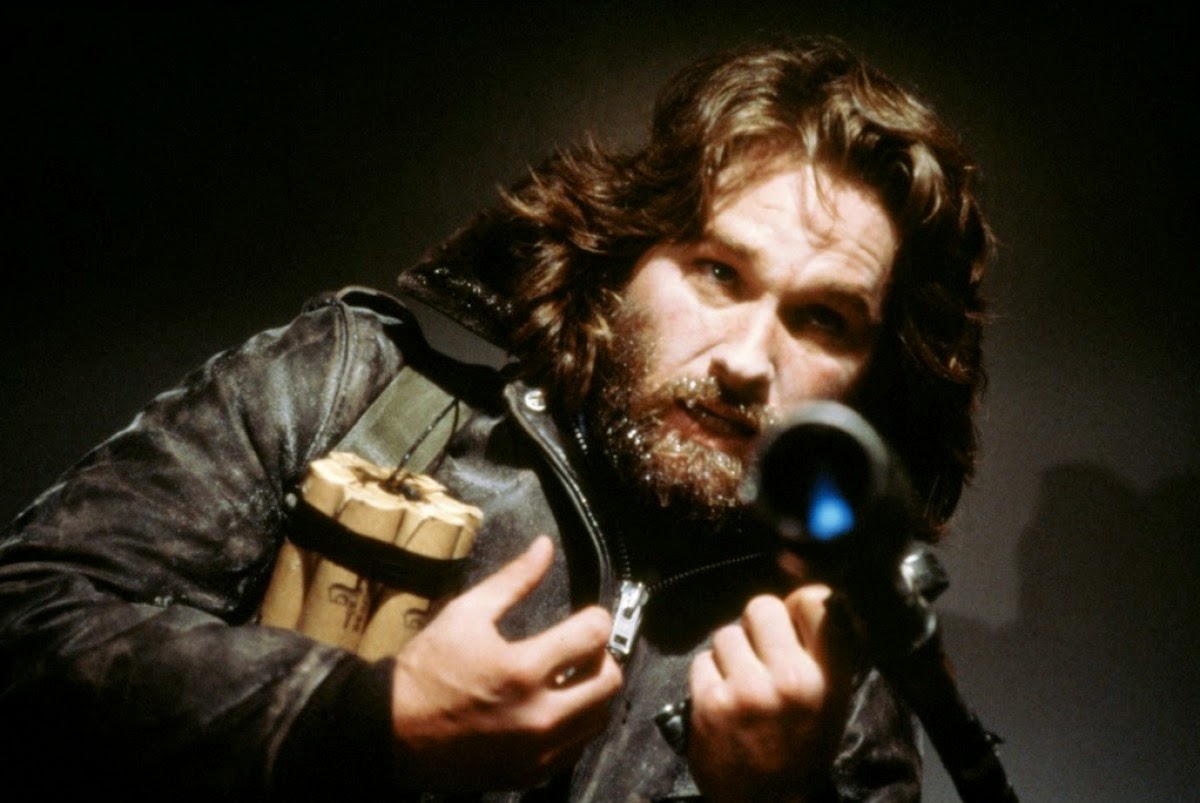

The Thing / *** (1982)

The story goes on and on through the reverb of the times: a trend dominates the output of the movies, and then along comes someone to louse the whole thing up. John Carpenter’s “The Thing,” about an alien life form wreaking havoc on a group of men trapped in a frigid landscape, is one of those beloved relics of the ‘80s that was considered the divisive game-changer for a genre in which premises like “Alien” had saturated the market with a relentless supply of bloodthirsty monsters jumping out from the shadows. Like a narrative sledgehammer, some would say it forever shattered the straightforward course of its cinematic family, and opened the sphere of possibilities up to much more horrific contemplations. Viewing the movie thirty years removed from that era, the ideas it presents are at least instantly distinctive; this is not a thriller in which ordinary beasts seek to destroy a gathering of unsuspecting victims, but one in which they take on the traits of Earthly organisms, absorb their DNA and walk among them as part of a convincing ruse to adapt to – and overtake – a new foreign environment. How unfortunate that the plot doesn’t know how to ride the wave as effectively as it should.

Tuesday, October 7, 2014

Devil / ***1/2 (2010)

The psychology of “Devil” offers such insightful and probing observations into the nature of evil that there is, at first, a desire to pause in cynical observation: what business does it all have being in a genre with such sensationalized standards? When it comes to the ever-so-exaggerated thrust of the satanic thriller formula, possibilities are usually reduced to over-the-top twaddle or flat-out silliness; there is seldom an inkling in anyone behind a movie camera to approach the subject with sensible faith, much less probing insights. Early narration in this movie is pitched like an audacious antithesis: because a critical observer in the ensuing events believes, wholeheartedly, in the old stories from childhood about the Devil’s looming influence in the world, it informs not only his perspective, but also ours. A good many questionable and horrific things occur to a selection of characters in isolation in just a short span of 80 minutes here – some of it mystifying, some of it disquieting – but none of it treads the line of implausible overkill, and the narrative deals with its horrors as conceivable facets that emerge from the grind of everyday life. And it’s also clever enough to stage the material so that all those involved share a deep-rooted commonality that unites them in their anguish. In one of many important scenes, as a police detective attempts to reason with the events while viewing them through security footage, he is offered prophetic words that seem to contrast his need for logical explanations: “there is a reason we are the audience.”

Monday, October 6, 2014

The Hills Have Eyes / ** (2006)

The geographical features referenced in the title of “The Hills Have Eyes” are a barren and desolate entity, scarred by fierce desert winds and intense sunlight that stretches miles upon miles in all directions. A truck carrying a trailer clobbers across the rugged terrain, carrying with it a family of California-bound passengers, who have little to no curiosity in the stories that these hills may or may not have to tell. Never does it dawn on them that the New Mexico landscape has been wounded by nuclear experiments and top-secret government tests; nor, for that matter, does anyone in the foreground get the sense that such tests have left behind rather menacing remains. Those hills tower over them like giant blankets of serenity, but the eyes of those ducking behind them are of a different kind, a different breed, a different intention. Had the protagonists known about these prospects before venturing into the area, no doubt they would have been eager to find themselves in an entirely different movie.

Sunday, October 5, 2014

A Nightmare on Elm Street / * (2010)

Maybe it is because I am so familiar with Wes Craven’s original “A Nightmare on Elm Street” – and all the ins and outs of its enduring legacy – that the modern remake of said film is at such an immediate disadvantage. Maybe the psychology of this idea was so potent that it carried on with vivid implications in the mind even now, negating the need to do a modern retelling. Or maybe, just maybe, opportunities to have an open mind are thwarted by the vulgar excess that permeates from the end result. Whatever rationale you take in with you, the new “Nightmare” film is definitely one of the more curious excursions through the excessive sensibilities of 21st-century horror movies. Produced by Michael Bay and directed by Samuel Bayer (the first feature film on his resume, no less), it replaces the fascinating context of Freddie Krueger’s existence with a seemingly endless exercise in violence and unrelenting pain. The fact that it does something so discouraging while still delivering effective production values goes to emphasize how misguided the genre’s architects have become in understanding what truly resonates in the eyes of their audiences.

Saturday, October 4, 2014

"A Nightmare on Elm Street" Revisited

“Here is a film that compares to some of the greats of the genre: a film that can be no closer to reality; a film that matches us against our true fears. No, there has never been a movie like it, and there never will be.” – taken from the original Cinemaphile review of “A Nightmare on Elm Street”

The transcending nature of “A Nightmare on Elm Street” is not in how it establishes a unique premise or even an important villain, but in how its actors buy into the material with such vivid implications. When Wes Craven first made his daring and graphic foray into the nightmarish visions of weary teenagers, how was he to know that it would provide more than just a momentary thrill for audiences of that generation? What were the odds that it would be cited so many decades later as a critical benchmark in the evolution of mainstream horror films? Could he have predicted that Freddie Krueger, such a vicious and unrelenting S.O.B., would also persist in the memory bank of notable movie villains? It is because his cast of relative unknowns believed in what they were submitting to with such unwavering conviction that the tragedy of their existence throbs on so effectively in our modern awareness, often informing the movies that continue to emerge from its shadows. Absorbing it now, thirty years from the first moment it shattered the dead teenager genre’s proverbial glass ceiling, is like reliving a primitive (but powerful) attempt at understanding a dangerous world of evil. It forces us to inherit these nightmares as if extensions of our own.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)