The term "dirty politics" is viewed under a loose definition because of the several ways it can be practiced in government, but Rod Lurie's "The Contender" casts an argument that is not only the most familiar, but perhaps also the most serious and defaming. Reflect back on the scandal that put President Bill Clinton in hot water with Congress: indeed it seems that the ideal approach in discrediting any politician's reputation is to go searching for some dirt of a sexual nature. What most utilizers of dirty politics do not always realize, however, is that leaking such information on someone's past may actually improve an image rather than tarnish it, simply because the general public accepts the fact that politicians are humans themselves, and in some cases should not always be held up to higher moral standards than those of any regular US citizen. Imagine Kenneth Starr's reaction, for instance, when the details of the Clinton sex scandal became public knowledge, and the president's approval rating skyrocketed as a result.

Friday, December 22, 2000

Dancer in the Dark / ***1/2 (2000)

So traumatic is the emotional charge established in "Dance In The Dark" that it will likely leave many of its viewers paralyzed with distress for days afterwards. With that kind of profound aftertaste comes the question of whether we as the viewers will be able to ultimately stomach the significant pain and suffering that the movie throws at us, especially judging from the mixed reception that the picture has received already. While several critics have hailed it as one of the year's crowning achievements, others have denounced it as an exercise in nihilism, without relief or constraint from the presence of a largely depressing atmosphere.

The Sixth Day / *** (2000)

Science has made broad leaps in allowing humans to do what they want to the Earth and its resources, but nothing quite as powerful as the process of cloning living organisms. We've read in newspapers and seen on television of how it is now possible for scientists to actually clone adult sheep, practically duplicating them without any fanfare or elaborate experimentation. But the process, needless to say, has been attacked even before it was technically possible, mostly by people who are concerned that mankind may be digging its own grave by practicing things it has no right to do. Now the concerns grow thicker day by day, as scientists ever-so-steadily creep towards the moment when they are able to successfully duplicate an actual human.

Vertical Limit / *** (2000)

The art of rock climbing is one of the most demanding and treacherous undertakings available to us as adventurers, in which every obstacle, every sound and every movement is an innuendo to a clouded outcome. Even the world's most experienced mountain daredevils are at high risk of losing their lives; every year, countless rock climbers tread the slopes of steep mountains with treacherous inclines, and never live long enough to tell of their nail-biting experiences. And yet why do we, year after year, continue to scale the world's great rock giants like Mt. Everest, taking the risk of putting a halt to our own existence? The challenge of something that is seemingly hopeless to conquer fills us with the adrenaline and audacity of a large fantasy warrior who keeps swinging his sword, but may never have the power to ultimately take down the dragon.

Friday, December 15, 2000

Charlie's Angels / * (2000)

If there were really movie curses, one might say that such a thing has befallen the "TV-to-movie" genre in the past decade. For some vague, unexplained reason or another, motion pictures that attempt to use popular television shows as source material suffer from bad cases of tone-deafness, underwritten plots, scarce character development, and a variety of other things. And yet excuses seem irrelevant; if a film has already established its plot and characters from something that existed farther back, doesn't that at least leave room for filmmakers to build on those grounds with something worthy of cinematic status?

Meet the Parents / ***1/2 (2000)

Imagining "Meet The Parents" without the brilliantly enticing comedy antics of Ben Stiller is like picturing "Aladdin" without the Robin Williams Genie. He's not just the funniest part of the picture; he's the backbone as well. Those who are solely concerned with the presence of actor Robert De Niro might be a little bewildered with that proclamation; after all, the latter has so much more potential on screen, especially in comedies (even though his two most recent, "The Adventures Of Rocky And Bullwinkle" and "Analyze This," are shameful trash). And yet this is not a big surprise by any standard, because in the recent years, we as moviegoers have seen Stiller thrive under the influence of bad taste, embarrassment, satire and physical comedy as if he were made for it. Case in point, the man may actually deserve comparisons to the greater comedians of cinema's past.

Red Planet / ** (2000)

Movie blockbusters appear to be trapped in an endless, disheartening cycle in which almost every concept is often materialized in pairs, with both productions usually being released so close in time that a nagging sense of deja vu is usually present by the second time around. Evidence to support this has been too numerous to maintain, but among the chief examples of this are the concepts of volcanic disaster ("Dante's Peak" and "Volcano"), asteroids or meteors ("Deep Impact" and "Armageddon"), gooey creature features ("Phantoms" and "Deep Rising"), and most recently, perilous ventures against the forces of nature ("The Perfect Storm" and "Vertical Limit"). One notable but wasted concept under this rule is that of Mars exploration, in which ambitious filmmakers have foreseen mankind finally placing feet on the sand of that elusive red planet, then realizing just how complicated the matter can turn in to. The first film under this idea was released in early 2000 under the name of "Mission To Mars," which was directed by Brian DePalma and featured an ensemble cast that had the ferocity and willpower of your average football team. Now comes "Red Planet," which is being unleashed on a cinema where most members of the audience will likely be asking themselves, "is there really room for another film centered on the idea of Mars exploration?"

Remember the Titans / *** (2000)

In Greek mythology, the Titans were a band of gods known loosely as "the strivers," who fought a long and hard war against their father, Uranus, before ultimately ending his life and assuming leadership of the free world. Imagine those gods dwelling in today's society, and the result would likely be something along the lines of the high school football team documented in Boaz Yakin's "Remember The Titans." In the year 1971, two high schools in Alexandria, Virginia, separated by their racial status, were merged into one, much to the protest of countless townsfolk who, at that time, believed racial mixing in the public domain was discouraging and unnecessary.

Unbreakable / * (2000)

There is perhaps nothing more pathetic than a movie that supersedes great expression with great contrivance, and M. Night Shyamalan's new thriller "Unbreakable" operates under such reasoning. When dealing with subject matter that borders between realistic and far-fetched, it's not a matter of how the story is set up or what the subject matter deals with: it's all in how you allow it to unfold which ultimately decides the merit. A movie that I am instantly reminded of, "Being John Malkovich," operates on a plain of existence where the inarguable absurdity is effective because of the influence of brilliant satire, strong details, and smart but wicked characterizations. "Unbreakable," like a cinematic opposite, is a long and odd marriage of fantasy and realism, but one that lacks substantial pace, decent characters, thrills, clarity, shape, and its own inspiration too often to ever be taken seriously.

Friday, December 8, 2000

The Art of Amalia / *** (2000)

Behind every great voice in music is a marvelous force possessing it, and "The Art Of Amália," a documentary from Bruno de Almeida, acquaints us with a pair that will never be forgotten… unless you are from the United States. Readers from other countries will have undoubtedly already heard her name by now; elsewhere, Amália Rodriguez, whose astonishing and successful career lasted for 60 years, is already seen as a legend among peers.

She was a Portuguese singer born into a low-class neighborhood of Lisbon in 1920, and at age four was already being asked to sing for the neighbors. In 1939 she began a career as a nightclub singer, captivating audiences with a seductive voice that melted even the coldest hearts, and into the 1940s a recording and movie career were already beginning to take shape. On home turf, her records and movies broke several records, while abroad, listeners slowly started catching on to the depth of her alluring persona.

She was a Portuguese singer born into a low-class neighborhood of Lisbon in 1920, and at age four was already being asked to sing for the neighbors. In 1939 she began a career as a nightclub singer, captivating audiences with a seductive voice that melted even the coldest hearts, and into the 1940s a recording and movie career were already beginning to take shape. On home turf, her records and movies broke several records, while abroad, listeners slowly started catching on to the depth of her alluring persona.

Bram Stoker's Dracula / **** (1992)

The movie vampire may be one of the oldest living screen creations, but it is also one of the few that has transcended time and formula, evolving with every new generation, always showing up to the cinema well-dressed, established, and heedful of its own deserved existence. It was born on the colorless German cameras of F.W. Murnau's classic silent "Nosferatu," and is once again being revived at the close of this year for Wes Craven's "Dracula 2000." What explains our constant admiration and positive outlook on its illustrious screen career? Perhaps the fact that the sharp-fanged creature is held to higher office than that of his distant cousins—in other words, is more intelligent, more thought-provoking, and most importantly, more realistic than other movie creatures, who have admittedly died out because of their repetitive (but probably ironclad) depiction's. We would normally expect a werewolf or mummy to do in movies the same traditional things, but the vampire has the bearings to take us by surprise, often taking action and choosing victims with unprecedented comfort. Embracing its existence has, needless to say, given it all the more reason to return again and again to the theater screen. We have spurred the bloodsucker's ego, you might say.

Get Carter / **1/2 (2000)

Remember that little running gag in the “Lethal Weapon” pictures where Danny Glover takes a deep breath after a physical stunt and announces that “he’s getting too old for this?” Perhaps Sylvester Stallone could take a study course on it. The now middle-aged but still-beefed up action star makes his anticipated return to the big screen from a three-year absence in “Get Carter,” with what one might assume is a departure role from his “Rambo”/“Rocky” days, but is actually no more than the routine, stamina-driven muscle man he has played throughout his career. The only significant difference this time around (other than the newly sophisticated wardrobe) is that the audience may have finally come to the realization of how tired and generic all of this really is. Stallone is a gifted actor in some aspects, no doubt, but is it possible to continuously take the same playing field without ever collapsing from exhaustion?

How the Grinch Stole Christmas / ** (2000)

The towering green visage in Dr. Seuss’ immortal tale of “How The Grinch Stole Christmas” is as famous a holiday figure as Santa Clause or Jesus Christ, prevailing in our imaginations as a reminder of how even the coldest hearts can renewed by a sense of unconditional faith and joy. An abstract reconstruction of the typical Ebenezer Scrooge persona, so to speak, Seuss’ eccentric antagonist lives on year after year, high in the mountains, watching the “Whos” down in “Whoville” relishing in the spirit of the holidays by lighting up trees, putting decorated wreaths on door handles, and exchanging gifts as if participating in a large birthday party. The story itself isn't a terribly involved one, true, but is played out with such vivid integrity and respect that, even for those who identify with the Grinch's actions of attempting to prevent the holiday's occurrence, reading it leaves behind a heartwarming lesson.

Little Nicky / 1/2* (2000)

“Little Nicky” is pure entertainment for the brain dead, a lifeless, frustrating travesty of comedy that suspends laughs for cringes, wit for idiocy, and pleasure for agony. The movie more than leaves us staring on in disbelief: it practically knocks our attention spans out cold. As a vehicle for comedian Adam Sandler, who was never that funny to begin with, the movie serves merely as the ultimate proof that if he has yet to make anything worthwhile, chances are that day will never come. Hopefully the masses will now finally accept that notion just as easily as I do.

Lucky Numbers / *1/2 (2000)

"Lucky Numbers" is like a TV game show without the consolation prize; a movie with a strong premise nailed down firmly, but no decent characters, inspiration, mild humor or even stable plot structure to top off the package. Is there too much to expect here first off considering the fact that John Travolta, the film's star, is just coming off his brief recession from "Battlefield Earth"? Not really. But low expectations don't mean we should just throw out even the most simple standards here, do they?

Friday, November 3, 2000

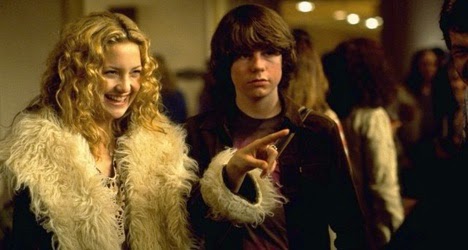

Almost Famous / **** (2000)

Cameron Crowe’s “Almost Famous” is the movie we’ve been waiting for amongst a muck of recent cinematic nightmares: the one so well made, so enticing and intelligent, that there comes a moment when you want to stand up and erupt into thunderous applause. It is one of the year’s crowning achievements, a film that not only builds on its characters but involves them in a compelling story that discovers rich messages through human drama and sophisticated comedy. That it has taken ten long months to arrive here makes the dismal experiences prior seem worth all the pain and suffering.

Bedazzled / *** (2000)

“Bedazzled” is a comedy about an ordinary single working male whose life is turned into a three-ring circus when he is given the opportunity to make seven—not three, but seven!—of his wishes come true. The catch? His soul will belong to the devil for an eternity as a result. In this case, the Prince of Darkness is given a new twist as a tall and luminous brunette, whose all-red wardrobe is seductive and chic, but isn’t nearly enough to convince an entire movie audience (much less the main character) the extent of her potential. Yet in a movie where diverse comedic exploits are executed so well and so vividly, does it matter that the villain lacks personality and comes off as a stale imitation of something much greater? Not really, and we can thank the off-the-wall, energetic protagonist because of this.

Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2 / *** (2000)

The phenomenon that is “The Blair Witch Project” may have scared the pants of countless viewers when it hit theaters last year, but few people realize that it also opened up a floodgate on the grounds of the film’s base setting—a small community in Maryland that the filmmakers had designated “Burkittsville”—where avid fans of the movie flock in droves year-round to, optimistically, catch a glimpse of something that gave the innovative horror flick its profound atmosphere. Now comes “Book Of Shadows: Blair Witch 2,” which makes a descent into the lives of five such individuals who were spurred by the popularity of the first film, and are now on a journey through the fictitious Burkittsville woods to see all the famous locations where the mockumentary was initially shot (all while the masses argue over the authenticity of the legend, too). Their trek is built on the same innocence and naivety that the three student filmmakers took with them when they went in search of the Blair Witch, but now with different results. In the first movie, our protagonists disappeared without a trace; this time around, the fate of curious eyes is more visible, but perhaps more tormenting as well.

Lost Souls / *1/2 (2000)

There is a background history attached to “Lost Souls” that may be long and involved, but is certainly more entertaining to hear about than watching the movie itself. Because religious thrillers have been showing up in theaters over the past year quite frequently, the movie’s makers chose to postpone the intended release date—late 1999—until the calendar was cleared of anything similar. Only one problem, though: trailers had already surfaced on new releases late last summer, and with the eminent delay, moviegoers could have easily grown tired of the wait and forgot about the picture altogether. Now that it has finally arrived in theaters, hopefully audiences will do just that.

Nurse Betty / **** (2000)

Neil LaBute’s “Nurse Betty” is one of the most audacious, bizarre and effectively conducted motion picture’s I’ve seen since “Pulp Fiction,” an over-the-map lampoon so well grounded on so many different levels, you gawk at it with a sense of sublime (but curious) appreciation. It tells the tale of a quirky housewife named Betty, who witnesses the brutal murder of her husband, and then drowns out her sorrows by absorbing the substance of several episodes from her favorite television soap opera. Daytime shows are generally used as innocent tools for escapism from some of our very own warped, complex lives, but Betty’s trauma has been so great, so extreme and hard-edged, she slips into a realm that mingles fantasy with reality, and actually begins to believe that she is linked to one of the show’s own characters. This inspires an intricate, offbeat storyline that operates on a consolidation of black comedy, satire, drama, romance, and at some points, even wild adventure.

Friday, October 27, 2000

Collectors / **** (2000)

The essence of the serial killer has been a perpetual fascination to society as far back as history is written, when warriors were immortalized for slaughtering thousands of people in bloody battles and outlaws like Jesse James were placed on pedestals every time their bullets pierced another innocent bystander. Little has changed with the passing of time; in fact, thanks to the unremitting involvement of our mass media, their accessibility is almost as extensive as that of someone like a super-model or a politician. Think I’m exaggerating? Then consider this for a moment: how come some television viewers of the late 60s/early 70s have admitted that, at the time, they could barely tell the difference between Jim Morisson and Charles Manson?

Friday, September 29, 2000

Fall 2000: A Preview of Things to Come

As the fall season begins to swing into gear at the cinema, moviegoers who reflect on the seasons that have already passed will undoubtedly be left in complete dismay. In the early months of the year, the theater screen was bombarded with a seemingly endless supply of half-baked material (unfunny comedies, pretentious thrillers, etc.), unleashed at a steady pace and laying the foundation for what could be the single worst year for movies in well over a decade. As those pictures subsided, we began seeing a touch of inspiration sprout out from the motion picture crop by early April (with pictures like “American Psycho”), and for a brief period of time, felt that the industry was heading in the right direction. But hopes were painfully dashed, alas, with the arrival of summer: a disappointing three-month journey through loud, obnoxious and even ridiculous blockbusters that trashed much hope for a worthwhile experience at the local multiplex. The period had its share of great successes, yes, but in all fairness, could not live up to most of its hype both critically and commercially. In fact, the highest grossing picture of the season—“Mission: Impossible 2”—made just a little over $200 million at the domestic box office, down from the $400+ million earned by last year's biggest summer flick, “Star Wars Episode 1—The Phantom Menace.”

"A" is for absurd

Why a proposed new MPAA film rating would be a waste of time

As the movie rating system is quarreled over by the masses for its productiveness as a model to arbitrate material viewed by young eyes, voices in the movie industry have proposed the implication of a new assessment into the Motion Picture Association of America’s rating system. This “A” rating, which would stand for “Adults Only,” is proposed to sit in between the “R” (Restricted) and the “NC-17” (No children 17 and under), essentially to relieve the pressure put on the R without drifting into the whereabouts of an NC-17, which suffers limited distribution because the public associates it with hard-core pornography. Such a suggestion, though, seems rather pointless in today’s rating system when the NC-17 shared similar proposal in the early 90s for exactly the same reason. The NC-17 and the A essentially mean the same thing: no children allowed. And if an A rating were ever passed, who’s to say it would not simply share the same fate as the infamous NC-17 did?

As the movie rating system is quarreled over by the masses for its productiveness as a model to arbitrate material viewed by young eyes, voices in the movie industry have proposed the implication of a new assessment into the Motion Picture Association of America’s rating system. This “A” rating, which would stand for “Adults Only,” is proposed to sit in between the “R” (Restricted) and the “NC-17” (No children 17 and under), essentially to relieve the pressure put on the R without drifting into the whereabouts of an NC-17, which suffers limited distribution because the public associates it with hard-core pornography. Such a suggestion, though, seems rather pointless in today’s rating system when the NC-17 shared similar proposal in the early 90s for exactly the same reason. The NC-17 and the A essentially mean the same thing: no children allowed. And if an A rating were ever passed, who’s to say it would not simply share the same fate as the infamous NC-17 did?

Friday, September 22, 2000

The Watcher / 1/2* (2000)

The recent influence of music videos in movies is slowly proving to be a nuisance to filmmakers looking to establish a distinctive style, but with “The Watcher,” its impact is so heavy that the film practically shoots off the scales and heads straight for overkill. What’s most sad is that the movie starts to tell an interesting story, but is then caught behind a shade of blotchy imagery and indistinctive camerawork too often to ever develop any sense of realism or excitement. By the time the fractious style actually lets up, it’s too late to save anything, for the plot has lost its desire and decides that a retread through serial killer formulas and off-the-wall logic is better than nothing.

Whipped / * (2000)

Filmmakers have had no problem in the recent past pushing the envelope for tastelessness, and perhaps no other genre defines that attribute better than the infamous sex comedy. Traditionally directed at personas who relish in exertions that a more mature society might consider perverse or unspeakable, these often outrageous romps, being the pinnacle of all cinematic bad tastes, are also some of the most amusing and hilarious pictures in production today. The recent success of “American Pie” and “There’s Something About Mary,” for instance, may offer insight into why the moviegoers are now so attracted to pictures pushing buttons: each challenges the restrictions, yes, but are performed at a level of initiative where surprise, embarrassment, satire and cheerfulness (traditional qualities of any solid comedy) erupt from the mix. But “Whipped,” a new endeavor of similar approach, is none of those things; its childish, detached take on the consequences of womanizing is an unpleasant experience to sit through, not just because it fails to match the sexual extremities with a sense of humor, but because it’s just plain dumb.

The Art of War / ** (2000)

“The Art Of War” is a heavily detailed descent into the world of international espionage, lit up by a barbecue of savory visual imagery, built on a solid premise, then linked by a reliable ensemble cast where each player is used significantly in the story. It’s a shame that the plot unravels long before the actual conspiracy does. The moviegoer who still has a thirst for some summer movie thrills might not mind in this situation, as the picture is simply loaded with well choreographed stunts and concise editing, but for those who are withdrawing from the season of thrills and avidly looking towards the fall release schedule, like me, visual excitement becomes secondary to a deep and compelling story. Such a quality is what this movie, like its nearest cousins—the Bond pictures and “Mission: Impossible 2”—fails to generate successfully.

The Crew / zero stars (2000)

“The Crew” is a childish, muggy and revolting mobster caper that is splintered by endless idiotic complexity, then sent off the deep end by the jaw-dropping participation from some of cinema’s most revered screen actors. Most moviegoers will likely compare it to the recent “Space Cowboys,” which made a similar outing by taking aging stars and splicing them into a story that required the kind of skill usually seen in the younger crowd of thespians. The basic difference? The premise of the first picture—old astronauts being launched into orbit—is at least constructed with genuine interest. How is it possible to show enthusiasm at a movie that matches its old codgers with a screenplay pasted together from various soap opera clichés?

Duets / *1/2 (2000)

When six spiritually unhappy individuals pair up in rather unrelated situations, they all find themselves on route to the same destination: a $5000 prize at an Omaha, Nebraska karaoke contest. One pair are newly-acquainted father and daughter, who bond throughout the movie on various ventures into karaoke competitions in local bars. The second pair consists of a business man who is overwrought with anxiety because his family ignores him, and an escaped convict with a voice that would captivate saints. The third is, rather pointlessly, a cab driver with the breakup blues, who agrees to take an ambitious waitress across the country to this contest just as long as she continues to perform sexual favors. For any person even slightly interested in seeing “Duets,” which is a road movie without any sense of direction or stability, perhaps these descriptions alone will help shape your final decision.

peter. / *** (2000)

If the term “less is more” still carries any significance with the average moviegoing crowd, than a simple little picture like “peter,” which is stripped down to the very rawest of human drama, could easily melt the hearts of viewers in ways that few films this year have. Maybe those audiences will have better luck in than me in getting past the drawbacks. The third feature film from ambitious director John Swon is easily one of the most smooth, appeasing independent pictures I have seen in recent memory, and yet one that doesn’t do its material complete justice. There’s nothing wrong with keeping things at a bare minimum, but shouldn’t it at least be a given to include a few side details so that we actually know what we are dealing with?

Friday, August 25, 2000

What Lies Beneath / *1/2 (2000)

There is an agonizing sense of déja vu that kicks in shortly after “What Lies Beneath” opens on the screen, as if all of the images, the twists, the outcomes, have been seen not so long ago. Anyone, of course, who has been tuned in to the film’s recent overexposure on television and in theaters knows why this feeling is induced: because every important moment in the movie itself has been in one way or another been used as promotion for the theatrical run, draining the product of its element of surprise. You know how it is when some big loud mouth tells you the entire plot to a film you have yet to see? “What Lies Beneath”s advertising campaign operates on those impulses.

Nutty Professor II: The Klumps / *1/2 (2000)

The utilization of bathroom humor is so relentlessly exercised in “Nutty Professor II: The Klumps” that it’s a wonder the movie doesn’t just flush itself down the toilet. Not that it would be missed or anything; with bad taste at a crest in the mainstream market (refer to “Scary Movie” for the latest), one can easily look somewhere else for a more satisfying use of gross-out comedy and usually come out ahead. Something like “Road Trip,” for instance, matches its repugnance with a sense of humor, while films like this assume that the inclusion of bad taste alone immediately equates with genuine laughs. Audiences will undoubtedly stare at this Eddie Murphy misfire with dismay and anger in their eyes; it is one of the most tone-deaf, sloppy excuses for comedy seen so far this year.

Hollow Man / ** (2000)

Paul Verhoeven’s “Hollow Man” is a technical achievement that is hard to resist, greatly heaped with wondrous images of striking detail and accuracy that—pardon the repetition of phrase—only special effects can master. But it is a movie, alas, littered by all the negative attire of a traditional summer blockbuster; unstable characters, weak reasoning, an incoherent plot, and sometimes, even general stupidity. It’s in the same vein as last summer’s “The Sixth Sense,” I guess; while the efforts showcased by these filmmakers are admirable, the hordes of conflicting energy drain the thrill of simply watching the visual style unfold on itself.

Coyote Ugly / ** (2000)

Watching “Coyote Ugly” is like navigating a rain forest without a survival guide; we gape at the dazzling spectacles, but there’s no telling where any of it will lead us or how much time it will waste. The movie is one of the most bizarre of its kind, executed without focus or integrity, yet provoked enough to keep dragging us through plot situation after plot situation as if there was some hope for a positive outcome. About halfway through the first act, I began to wonder with a sense of frustration, “what is the purpose of going any further?” You can’t expect too much from any movie, after all, that tries to be a buddy picture, a loose coming-of-age tale, and a PG-13 version of “Showgirls” all at the same time.

The Cell / ***1/2 (2000)

The persistent debates between film critics have perhaps never spawned a divide as broad as the one we see with Tarsem Singn’s “The Cell.” On one hand, we have writers like Jeanne Aufmuth heralding this new theatrical arrival as “a mind-bending, acid-trip of a movie—fresh, disturbing, and inimitable”; on the other, we have critics like T.W. Siebert denouncing the picture as a “reprehensible and gratuitous piece of garbage.” Heck, there are those who fall somewhere in between the branched consensus (such as Dan Jardine, who admits that the film has “stunning production design, costumes and special effects,” but suffers from a “meagre plot”). In situations like these, the average moviegoer who reads reviews in search of a recommendation will be admittedly left in limbo, making it almost necessary for them to go and see the picture for themselves to see which side of the quarrel they fall on. The question of “who is right and who is wrong” is subjective in the end, however, as there is no definite answer, for any of us, when it comes to a movie like “The Cell.” All we can do is accept the film for what we see it as: a perfect blend of style and substance, a special effects feast that redeems a dismal story, a mediocre production with some strokes of merit, or a total misfire.

Bless the Child / ** (2000)

When the night sky is shimmered by the sudden appearance of a bright and distinctive star, nurse Maggie O’Connor, whose religious beliefs are questionable after three miscarriages and a lengthy divorce, is told by a nearby bus passenger that it denotes the arrival of a gift from the heavens. This particular star, you see, has not been seen since the days of the birth of Jesus Christ, and as it looms bright and large high in the sky as if some heavenly presence is watching for the birth of a new savior, Maggie is greeted at her front door by her drug addict sister and, of course, a newly born child. This is hardly coincidental, as audiences will be able to tell, but it is exactly the kind of observation that makes “Bless The Child” the newest in a long line of narratively dreary satanic-like thrillers, as characters spend countless time discussing and studying different theories behind the this “special” little girl, all while we have had the mystery figured out since the very beginning.

Saturday, July 29, 2000

Boys and Girls / **1/2 (2000)

“Boys And Girls” has characters bursting with energy so intense and vibrant that you wish there was a more interesting plot to keep them occupied. At a point when movie personas are gauzy rip-offs of smarter characters from older pictures, their arrival onto the screen is met with warm embracement, especially from those who (like myself) are tired of the incessant idiotic depiction of America’s youth through the eyes of actors who aren’t even teenagers to begin with. Like “American Pie,” here is a radiant display of the sauciness, sophistication and intelligence of students, and how their skills can literally wreak havoc in the lives of those around them.

Chicken Run / ***1/2 (2000)

The claymation technique that is utilized in Dreamworks’ charming “Chicken Run” is one of the many masterful movie art forms that has become lost amongst the upheaval of more mainstream (and usually less fulfilling) approaches, and the one format of movie animation in which the primitive realm it is cemented to still has a tendency of enticing audiences more than evolved ones. After computers took over the field in the mid 1980s, movie animation is consistently trying to push the envelope, introducing spectacular techniques so frequently that there is little opportunity to give them a sense of diversity.

Disney's The Kid / *** (2000)

“Disney’s The Kid” is the type of movie that walks thin lines dividing ripe emotion with cheap sentiment, but is so confident in its own execution that none of us really mind. Self-assurance is usually the first positive notch towards bandaging the infectious emotional wounds that plague productions like this, but in the recent years, consistent contrivance has turned most melodramas into a display of groans and complaints from the moviegoers who endure them. You can usually tell the difference between the two; a film aiming for some sort of plausibility in its sentiment will anchor the grievances and/or happy occasions on a significant plot structure without over-the-top complexion. A latter example would be a film that devotes its entire time to unleashing endless tear-jerker situations back-to-back without any dramatic or narrative purpose (other than to coerce audiences into pulling out tissues).

Me, Myself & Irene / * (2000)

“Me, Myself & Irene” is exactly what happens when filmmakers stake into new territory, lose sensible navigation, fail to realize their mistake and repeat the process for lack of better enterprises. After their lame and pretentious effort that is “Outside Providence,” one might have hoped that the brothers Farrelly, famous for their hits like “Dumb And Dumber” and “There’s Something About Mary,” would retrace the steps that gave them success in the first place for their next creative endeavor. That, needless to say, might have been the last thing on their minds, especially since the film features the comedic return of Jim Carrey, whom one reader of mine says “can make any screenplay worth the ticket price.” Little did he fail to realize that there is material sometimes so bad that no one can redeem its frequent inadequacies.

The Patriot / *1/2 (2000)

“The Patriot” is a blood-soaked, incessantly gory clutter of a movie that tries hard to pass itself off as a noble war epic seethed in family values and national honor, and then expects us not to distinguish its endless contradictions or vast narrative shortcomings. Too bad those aren’t even the extents of the problems. Directed and produced by the same pair who masterminded the summer garbage “Independence Day” and “Godzilla” a few years back, this loathsome, sour and often confusing endeavor sponges off the formulas of half-a-dozen other war films but exchanges the realistic intensity with gratuitous and over-exercised bloodshed. The fact that it uses an event like the Revolutionary war to serve its own warped propaganda gives an extra twist to the knife in our backsides.

The Perfect Storm / ** (2000)

Wolfgang Petersen’s “The Perfect Storm” is the kind of disaster picture in which ships tossing around through mile-high water waves is inclined to so much observation that the narrative drowns out long before any climax is attained. And this is sad, to a certain extent, because the infamous genre revolved around natural disasters can at times dish out rather successful endeavors that combine both mind-numbing sequences of utter catastrophe with heartfelt human emotion. “Disaster dramas” are what they should be called: the few that lay waste to creation, but are courageous enough to peer into the eyes of a victim and ask, “how does this affect us as human beings?” Most of them, like “Volcano,” are too concerned with loud sound and visual effects to stand back and admire the human spirit of the stories.

Scary Movie / ** (2000)

In the opening moments of “Scary Movie,” Carmen Electra is taunted by a man dressed in a cloak and ghost mask, whose voice is disguised so well that she doesn’t know who it is when he asks what her name is. Why does he wish to know her name? “Scream” taught us in 1996 that killers like to know exactly who they are looking at, but this particular man is not checking her out from a distance; rather, he is gloating over her latest spread in Playboy. Suddenly a chase breaks out, and the murderer plunges a knife into her chest, pulling out a breast implant upon release of the weapon. These early scenes have such positive energy between victim and murderer that we suddenly see glimmers of hope, as if, at long last, the dead and buried spoof genre has found its shovel. But alas, like all of its ancestors, “Scary Movie” is a comedy stumbling around on stilts, a film so dreary, shapeless and juvenile that the laughs are low and attention spans become disconnected before the first half hour is through.

Shaft / ** (2000)

Of the endless chain of flicks that came out of cinema’s “blaxploitation” era in the early 1970s, none have quite gone down as revered and well-respected as “Shaft” from 1971. Slick, hip and stylistic, with broad strokes of energy around the edges (particularly in the unforgettable title them from Isaac Hayes), Gordon Parks’s film about a cop who played by no rules but his own was an early example of how action movies could be given an array of freedom without technology or loads of dough clogging production values. It was hardly a classic, especially given its rather inane narrative, but acceptable all the same; not many movies, after all, came out of the blaxploitation craze that were not mulled down by some kind of displeasing point of view (not that I’m one to speak wholeheartedly about the genre’s scope given my limited wisdom on it).

X-Men / ***1/2 (2000)

The genetic evolution of the human being, as we are told at the beginning of Bryan Singer’s “X-Men,” takes a gigantic leap every hundred centuries or so, creating a rift between those affected with the transformation and those who remain undisturbed by it. At the end of the 20th century, such developments have unleashed a society of superhumans: people who exhibit altered physical or mental attributes which allow them to attain capacities that no standard being could hope to achieve. Any person who has fallen victim to this transformation should be grateful to have been given this chance, but since the broad scope of humanity refuses to accept them because of their differences, these traits are actually regarded as punishments. In such a society, the word “mutant,” which they are referred to as, becomes synonymous with “freak.”

Friday, June 23, 2000

Big Momma's House / * (2000)

“Big Momma’s House” makes a severe error in judgment by assuming that, when slim men dress in drag in comedies, playing overweight women in their twilight years is the compulsory approach. This plunge has already seen more than its fair share of interpretations in the cinema, and as such, has become a tired and clichéd instrument of movie making. The idea was most recently milked to death by comedies such as “Mrs. Doubtfire” and “The Nutty Professor,” but those films, at least, are ambitious in certain ways. The filmmakers behind “Big Momma’s House” seem to only have one desire in mind: to trap an actor in an oversized body suit, have him wander around and, ever so often, shout out insipid dialogue to see if moviegoers’ interest will last long in the less-than-amusing transformation.

Fantasia 2000 / **** (2000)

Like most prominent filmmakers, Walt Disney was a pioneer of cinematic innovation, and when the success of animation marked a new turning point in filmmaking in 1937 with “Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs,” the idea of blending classical music and detailed hand drawings in the movies was an experiment too promising to ignore. Over half a century after that test, his endeavors are proudly recognized across the globe; the now-legendary production of “Fantasia,” originally dubbed by Disney “The Concert Feature,” remains the benchmark for the continuing growth of animation and the imaginative minds that help bring it to life. Few people are able to see the picture (or rather, the event) and not remember the beautiful, colorful images that visually represent the brilliant musical compositions of composers such as Beethoven and Bach. In most respects, the perception of Mickey Mouse wearing the magician’s hat has become the perennial Disney trademark.

Gone In Sixty Seconds / *1/2 (2000)

Movies like “Gone In Sixty Seconds” are the least-difficult to sit through during the summer because they follow such simple-minded and routine formulas that theaters might as well provide checklists. It opens with the assumption that experienced car thieves have the audacity to cease all their illegal activities if it means that younger siblings would not follow in their footsteps. How noble of them. Then the movie prepares an obligatory backfire by having the younger sibling get mistakenly involved with a powerful local criminal, who will instigate the revival of these illegalities so that he will wind up with 50 rare stolen cars, and the thieves will save the life of the innocent bystander. Once all of these conditions are absorbed, only one question remains: how many times have we seen all of this before, only in different moods and premises? Those who flock to theaters at the mere mention of a film associated with Jerry Bruckheimer could give you a direct answer.

The Last Broadcast / *** (1997)

In order to get novel but low-key movies noticed, it’s essential for someone to bring the idea into the mainstream. Such is the scenario which brought us the sleeper hit “The Blair Witch Project” last year, the low budget, unconventional thriller that documented the descent of three filmmakers into Maryland woods who were in search of a legend, but found something more terrifying than anyone could have imagined. Like so many new ideas, the “mockumentary” approach of the film has generated massive interest in moviegoers, who have sifted through countless formulaic horror movies in the recent past while in search of successful thrills. Inevitable, it seems, that two sequels to the Blair Witch saga are in the works, along with various clones.

Mission: Impossible 2 / *1/2 (2000)

When it comes to in-your-face action flicks, director John Woo is a force to be reckoned with. Peering into his past, we see a body of work overflowing with wondrous drive—works like “Face/Off” and “Broken Arrow,” which are plagued by shortcomings as narratives, but are guaranteed show-stoppers in regards to the involved action sequences. He approaches them in a way few blockbuster directors do, using unique camera angles and swift but precise editing to ensure the stunts look both inventive and plausible. If only he were given a decent script to go along with these ambitious convictions, though.

Road Trip / **1/2 (2000)

Teen comedy has a history of skirting the line between plausible and pretentious, and with the ambitious “Road Trip,” laughs fly off the screen so fast and consistently that, eventually, the movie shifts into overdrive and practically commits suicide. One can easily smile at the endless supply of quirks offered here: crude sexual undertones, jolting irony and biting one-liners, just to name a few. And yet the picture loses its push just when things are heating up; it assumes that audiences have been manipulated enough to be amused by an oncoming chain of breast shots and banalities of the elderly and the obese. Most will sense something terribly wrong once the film gets so desperate for plausible laughs that a characters winds up holding a mouse in his hands to imitate a snake on the verge of devouring its next meal.

Titan A.E. / **** (2000)

With theater ticket prices on the hike again, many a moviegoer are beginning to utilize foresight in the choices they make regarding what movies to see. Since no one wants to regret losing all that money on something dismal and unrewarding, their approach to most films is weary, and understandably so, given the fact that 2000 is already one of the worst years for movies in ages. Few pictures have offered a significant and rewarding experience (the best exceptions being “American Psycho” and “Gladiator”), while most have given us reason to question the existence of God (the evident choices being “Battlefield Earth” and “Next Friday.”). Now that the summer season is underway at the cinema, hope for is rising for something more stable than the typical junk of previous months.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)

.jpg)