I began the 2010s uncertain of my place in the slipstream of film criticism, and closed it out firmly lodged somewhere between enthusiastic and mystified. Whatever emotion I experienced sitting in a theater, be it involved in something celebratory or a feeling of total despair, the movies never abandoned me; they persisted like stubborn reminders of what is important about the art form, whether it was in a literal sense or in some twisted ironic way, even as some might have represented everything wrong about this strange little industry.

The decade supplied ammunition for both arguments. It was the time of new and exciting voices like Yorgos Lanthimos and Christian Petzold, and of lazy underachievers like Uwe Boll. It was the age of billion-dollar blockbusters, and tiresome trends yielding colossal flops. Established filmmakers plodded along in a career trajectory that allowed for new and exciting ventures. Some promising newcomers like David Robert Mitchell, meanwhile, diversified their portfolio between solid entertainments (“It Follows”) and disastrous aberrations (“Under the Silver Lake”). But all the same we showed up, watched, and responded with our constant passion as moviegoers. A great film was never far from grasp at local art-house movie houses; so, too, was a bad one inevitably playing in the mainstream chains, where it stood a better chance of rising to notoriety, unintentional or otherwise. The common bond among all of them, you could say, was their ability to remind us that there is a bigger world outside of the Walt Disney brand, whose choke-hold on the financial market of moviegoing has cast an impenetrable shadow going into the next decade.

Tuesday, December 31, 2019

Tuesday, December 24, 2019

Hell House, LLC 3: Lake of Fire / **1/2 (2019)

Two-thirds of the newest “Hell House” picture is the work of a man who is intrigued by the undiscovered. After finding comfort in the throes of low-tech visual manipulation and nuanced camerawork to achieve great thrills in the middle of a haunted hotel, he comes to “Lake of Fire” energized by what felt missing: the very need to expand on the possibilities of his great source. A brief confessional on camera emphasizes this urge: a cable show host, Vanessa Shepherd, contemplates the strange nature of Abaddon, New York, and how unsolved supernatural events have apparently extended beyond the hotel itself. Why are they are never covered in the local press? Because, of course, they aren’t as glamorous or sensational. Unfortunately, her reveal is interrupted by a bystander while on location and she is never able to finish the thought. But the seed is firmly planted in the audience, who watches on patiently while a business tycoon invests money and resources into turning the former hotel into a seasonal theater. The goal: to create an interactive Halloween performance of “Faust” inside a building rich in supernatural history. Perhaps “Faust,” about a struggle of a man’s temptations between God and Satan, ought to have been the key warning. Wouldn’t the many deaths and disappearances have been enough to sway away most sensible people from participating here?

Tuesday, December 10, 2019

Parasite / **** (2019)

The vicious cycle coalescing beneath class systems is a detail that draws much ire out of Bong Joon-ho, whose films all suggest a world where life and routine is usually mandated by where you fall in the system privilege. Not content to simply show sides of the structure clashing, he abandons them into a philosophical clarity that sees rot and cynicism as shared values; just as the wealthy are set in the method of clinging to their narrow vision, so do the impoverished embrace the seedy underbelly to propel their obligatory agendas. Both, perhaps, are what contribute to the ambiguous implication supplied by the title of “Parasite,” where a filmmaker never quite indicts a single target. Yet the argument inspires all the expected questions without direct answers. Are the characters in a wealthy family the victims of what will eventually transpire, or are they inconsolable leeches of an imbalanced society? Are we expected to see the poverty-stricken Kim family as sponges for all the trouble they are dealt, or as survivors adapting rapidly to the unpredictable whims of the hierarchy? The challenge offered in this audacious and engrossing little film barely reflects its deeper nature, which plays less like a standard narrative and more like a living organism adapting scene after scene to a volatile habitat of strange and mystifying nightmares.

Saturday, November 16, 2019

"Psycho" Revisited

Abnormal even among the more challenging horror films of today, Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho” abandons its central character arc for a much more unexpected second just as the plot begins to wade deeper waters. There is an observation made in the preceding scenes that suggest that possibility – namely, a moment when Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) realizes almost prematurely that she must return home and give up the money she stole from her employer – but our wildest notions of the conflict could scarcely predict the outcome of her abrupt escape down a rainy highway. Most of the familiar rules in horror were far from being accepted as part of the formula handbook, but a constant among the early prototypes was the use of one primary character as a source of study. Yet here she was, a mere 48 minutes into a film, showering at a rundown motel owned by an eccentric loner, and being snuck up on by a shadowy figure destined to stab her to death. If the shock of the incident remains startling for its perfect technical modulation – meticulous edits, a piercing soundtrack, out-of-focus details that obscured the numerous wounds – then its broader effect came entirely down to audacity. No other mainstream film up to that point committed itself to such nerve to shatter the comfortable borders of a story, and to this day it remains peerless among a growing arsenal of broadening genre standards.

Saturday, November 2, 2019

The Lighthouse / ***1/2 (2019)

On the edge of a rock hugging the violent sea, a weathered lighthouse affirms the mission of two men stalled on a mental tightrope. They plod day and night through a routine that always leads to one outcome: ensuring the illuminating glow of the tower never dims, even as the most turbulent storms loom relentlessly overhead. But a day comes when the winds shift, casting doubt on their own perseverance; a nor’easter draws down like a force of punishment, until their demeanors – one sardonic, the other silent and morose – collide on each other with disturbing gravitas. On the other side of the struggle is only more of the same: a cycle without relief or certainty, unless the primary conviction is to stilt the moods of those eager viewers watching below the projector’s light. Their feelings, I reckon, might parallel what some of the early audiences thought upon first seeing “The Shining,” also about people who were driven mad by isolation. Did the slow plod through a tonal labyrinth, too, undermine their defenses enough to amplify the horror of the climax? Were they submissive to the visual attack, and did it negate any questions of logic they might have had? Robert Egger’s eerie, hypnotic new film mirrors many of those possibilities and finds something rather interesting buried beneath: an imagination that escalates its visions into the fantastical and absurd.

Tuesday, October 8, 2019

Joker / *1/2 (2019)

Long before mental health awareness pigeonholed the Joker personality as a damaged loser prodding psychological wounds, Bob Kane’s villain existed somewhere between the cynical and the sardonic, like an instrument of showy destruction joyously sticking a thorn into the sides of his opposition. If the early comic book readers never quite saw him as a great monster, it’s because the material was emboldened by the irony of the façade; the clown makeup and the ridiculous cackle were behaviors of cartoon personalities rather than straight madmen. But now we have crossed into the space where graphic yarns have lost that distinction and have become living embodiments of the terror within. With that the villains of Gotham City have gone through a considerable transformation, starting with the Tim Burton “Batman” films, where criminal minds were founded by childhood trauma rather than a simple need to be devious. Christopher Nolan’s adaptations took this prospect even further; gone were the absurdist production designs, and in their place were tangible forces of darkness that seemed as if they were walking past us on any ordinary city street. The most profound modern realization of the Joker belonged to “The Dark Knight,” where Heath Ledger took the idea beyond the source’s own possibility and showed us a broken personality whose chaotic tendencies were like a roadmap leading back to a mind wrought with personal hell. Alas, now we must contend with Todd Phillips’s miserable “Joker,” about a man who knows no humor, slogs through a world riddled in corruption and limitation, and finds escape in unleashing the sort of gratuity and destruction usually reserved for cynical horror films.

Thursday, October 3, 2019

Ad Astra / ***1/2 (2019)

The most reflective moment in “Ad Astra” takes place just outside the orbit of Neptune, seen hovering in the distance like the most vulgar mood indicator in a sci-fi film since the ominous planet in “Solaris.” While its energies don’t directly influence the emotional demeanors of those nearby, their attitudes have all but foregone a similar deep melancholy: a recognition that there may be only deafening solitude in the great emptiness that is space. Up to that point, James Gray’s mysterious film foreshadows that statement via a morose internal monologue by his lead star: Roy McBride (Brad Pitt), an astronaut who has abandoned a family on Earth to take to the same stars his father disappeared into decades before. But when he must confront the man he feels abandoned him, what can they say to one another? Was his father’s sacrifice really all terrible given that Roy has followed the same trajectory? Aboard the rusting ship that once housed a crew seeking intelligent life, two men lose the desire to form a cogent reasoning and can only submit, quietly, to a discovery that ought to have been obvious all along. What is not as discernable, at least until those final scenes, is how Gray will fill his audience with the same sense of dread. If we come to science fiction to understand the unknown and make it palpable, here is a movie that suggests we are naive in assuming greater secrets beyond our own corroding existence.

Friday, September 20, 2019

The Burning / *** (1981)

Is Tony Maylam’s “The Burning” a dead teenager horror film at all, or an ambitious homage to giallo masquerading as a slasher? The possibility occupied my brain while the material on screen lumbered along slowly and conventionally, positioning itself for a checklist of obligatory sequences that we come to expect of genre vehicles. The key difference is slight yet noteworthy: instead of recycling the sort of artificial showmanship that usually informed most of the violence in the early horror franchises, the movie creates a rather convincing aesthetic of gore, right down to the gaping wounds in a neck and the severing of someone’s fingers. The blood, meanwhile, splatters in the same ambitious fashion usually seen in the films of Mario Bava, who often used it more like a substance for a paintbrush. Where does an otherwise aimless descent into superficial formula staples get the gall to be so painstaking about its own visuals? Or the patience, for that matter? Maylam’s benefit may be that he, unlike any number of stand-in cameramen pretending to be legitimate filmmakers in that time, took the time to study up on his peers in order to best them at their own routine.

Thursday, September 12, 2019

It Chapter Two / *** (2019)

In theory “It: Chapter Two” ought to be a straightforward document about a monster’s final encounter with seven surviving teenagers destined to destroy him, but in truth it’s more about the pain of buried memories – about how grief and torment have been so great that survivors have placed protective barriers over their recollections, even as they are forced to relive them in order to understand their relevance in the present. Not 10 minutes into this long-awaited sequel and the distinction is firmly established: as the members of the Losers Club gather after 27 years of life experiences away from the horrors of their childhood, they discover a great significance in drifting consciously into flashbacks, as if peering through photographs that conceal necessary answers. Clues and perspectives rush to them in a torrent of emotion, arming them with what will turn out to be the right defenses to conquer their lifelong enemy. But who is the real barrier here: a menacing clown that feasts on defenseless loners, or the unresolved fears they have suppressed for nearly three decades? It is part of the skill of a good horror movie to reflect on its subjects throughout any ordeal thrown at them, and much like its predecessor, the new film is a well-made attempt to dissect the nightmares that come with being young and impressionable in a world riddled with cruelties.

Wednesday, September 4, 2019

The Condemned / zero stars (2007)

Ten convicts. One game. Nine must die. The victor walks free. This isn’t an inherently flawed plot description if viewed through the lens of a well-intentioned eye, but the offense that is “The Condemned” exploits it for nothing more than lurid, gut-crushing violence – and in the process becomes one of the most deplorable moviegoing experiences of my life. The very idea of describing these scenes fills me with a dread I rarely recognize – you know, the sort that comes rising from the pit of your stomach when you’re in the throes of danger, or about to witness something causing agony or pain to another? If that’s just a taste of what is possible, then imagine what the poor suckers involved in the movie were thinking. Did they connect with this idea in any substantial way beyond their monetary greed? Was it sold to them as a sincere attempt at understanding our perverse voyeurism? Or were they all part of an elaborate joke being played on the victims known as the audience? I mourned their innocence just as much as they must have wept over the decimation of their careers. Towards the end, a single character stares angrily in the direction of the source of chaos, and he asks scornfully, “are you really trying to save them?” “No,” she retorts, “I was trying to save you.” How strangely comical it must have been for anyone to utter those words in the same room as a director and writer who ought to have seen them as self-reflective.

Monday, August 26, 2019

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood / ***1/2 (2019)

Towards the middle of “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood,” Quentin Tarantino casually reveals his intentions in a sequence involving an audacious clash of history and fiction. Already he has established the key relationship between an actor, Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio), and his stunt double, Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt), but not until there is a western-style standoff with members of the Manson family do we sense the gravitas of their roles; just as Cliff is the one exposed to all the danger on the set, so does he carry that burden off-screen, where his friend and partner is usually sulking in self-pity. This, we soon realize, is the destiny that will foreshadow how the movie must play out: with the stunt man ready to face off against a violent threat emerging in the shadows while the other, more aloof personality, is left to remain mostly ambivalent in the backdrop. Is Tarantino saying something about his own ideals in these characters, who are like two halves of a fully contained behavioral system? Is his Rick Dalton, a neurotic and insecure man reflecting on the monotonous tide of his career, an avatar that he projects all his fears onto, while Cliff symbolizes the more youthful scope of his own chutzpah? Theirs is a union necessary to a film that would otherwise collapse without it; they bring guidance and perspective to an atmosphere that is essentially a eulogy to the old ways of Hollywood.

Saturday, August 10, 2019

Children of the Corn / * (1984)

A great evil lurks in the fields of Gatlin, known only to a select few who have been ensnared by its mental claws. All those who do not accept it – mostly adults – are destined to become its famous first victims, as shown in an early sequence where the young narrator watches as rows of adolescents slaughter them at a local diner. Few beyond the town’s borders know of what transpired there, but a token mechanic living on the outskirts provides all the perfunctory warnings to those passing through. “Well, folks in Gatlin’s got a religion,” he tells a couple searching for a phone. “They don’t like outsiders.” And so the stage is set for the two oblivious leads to get lost on the road, wander into the abandoned town square and begin a bloody face-off with kids who otherwise would be carried off to youth detention centers in any normal reality. Piece all these elements together and you have the default premise for countless teenage splatter films; add in a few extra touches like excess violence with farm weapons, bad child actors mugging for screen time and a preacher who sounds like he is choking out his ponderous sermons, and what you have is the greater offense of “Children of the Corn.”

Wednesday, July 31, 2019

Tenderness of the Wolves / **1/2 (1973)

You can deduce a lot about a madman by the way he is perceived by others. The conventional anecdotes are the staple of many retellings of their crimes. They were loners. They didn’t talk to anyone. Some thought of them as socially awkward. They never stood out, always seeming to disappear among the faces in crowds. And then there are the sorts whose sins come as a total surprise to onlookers who otherwise thought highly of the culprits. “No one expected a sweet man like him to murder those boys,” a resident in Houston, Texas once said of Dean Corll. “I considered him a friend, and I’m stunned by this all,” another spoke of John Wayne Gacy, shortly after his house was ransacked and 29 bodies were pulled from the crawlspace beneath. The more lurid and disturbing maniacs cast a long shadow of doubt amongst their peers, who would never assume something so heinous behind a set of charismatic eyes. That also means their crime sprees tend to be long and drawn out, no doubt since they provide few (if any) warnings signs. Yet as I watched “Tenderness of the Wolves,” a dramatic reenactment of the many crimes of Fritz Haarmann, I was struck by the almost cheerful ambivalence of his friends, lovers and onlookers as he routinely got away with the vicious killings of teenage runaways. Consider a scene, for example, when the notorious “Werewolf of Hannover” drops a slab of meat on the counter of a lady’s establishment, and she expresses glee at his arrival. He apparently doubles as a butcher, in addition to being a police informant. Others, however, find the texture of his delivery odd and off-putting (no one questions where it comes from, of course). But the restraint of curiosity belongs to a single pitch: what purpose is there to suspect a man so charismatic of engaging in anything so heinous? This is a movie that theorizes people are more content to look the other way on what is obvious than to deal with it directly.

Friday, July 19, 2019

Midsommar / *** (2019)

The insurmountable tension between the main characters of “Midsommar” would usually indicate the foreshadowing of some sort of dramatic showdown, but for Ari Aster, a filmmaker who prefers to quietly agonize over more unconventional horrors, it is simply a wound for the story to exploit much later, when the narrative pummels down on it like a merciless weapon. Up to that point, the leads dance around cordial exchanges as if attempting to subvert the topic of their mutual dislike, and brief arguments seem held back by a suspicion that it will all explode into something more elaborate. But those confrontations never come, usually because the faces are gradually picked off by something more volatile in the nearby shadows. Is Aster insinuating, perhaps, that not dealing with an issue like this early on is a gateway to tragedies beyond your control? Or is he of the belief that people’s individual personality conflicts are pointless when viewed in a broader sweep of cynicism? However you choose to approach the movie will do little to quell the macabre connotations of the outcome, which uses these behavioral details like roadblocks preventing eventual casualties from detecting more obvious fates. Theirs is less a story than it is a series of actions preceding inexplicable bloodshed.

Sunday, July 14, 2019

Birds of Passage / **** (2019)

Tradition is a social construct eroding in the sweep of modern values. This is one of the key observations made by Marxist E. J. Hobsbawm, who also suggests their prevalence in a series of more dangerous cultural identities, including the same nationalism that lead to Hitler’s Germany. One wonders how the writers of “Birds of Passage” would feel about this assessment – whether they would, quite possibly, concede that the behaviors of their characters seem like gateways to troubling histories, or if they, like their customs, are simply undermined (or destroyed) by more cynical paradigms. Evidence before them could support either theory. The scene: an indigenous tribe of Wayuu natives in the plains of Colombia is celebrating the coming-of-age of Zaida, the daughter of the family matriarch, and she has acquired the notice of Rapayet, a member of the neighboring family, who announces his intention to marry her. The snag in his desires is Ursula, Zaida’s mother, who insists on a steep dowry. Protective and dismissive, she believes he will never be able to pay it. But as days pass and Rapayet is seen caught up in a monetary agenda with foreign vacationers, her demands are met. Unfortunately, this does more than promise him the bride he seeks; it also sets the early stages in motion for what will become the gestation period of the Colombian drug trade, which found footing in the late 1960s and became the source of a cycle of violence that continues well into the 21st century.

Wednesday, July 3, 2019

Christine / *** (1983)

John Carpenter’s “Christine” is a well-made attempt to bring sincerity to absurdity, without calling much attention to the disconnects of logic that would otherwise collapse the story. Imagine how frustrating that must have been for a man that was otherwise absorbed by more palpable realities. After “Halloween” established him as a filmmaker obsessed with the possible and “Escape from New York” moved him towards a more prophetic sense of storytelling, along came a ridiculous screen treatment involving a killer car and his nutjob owner who mow down the town’s teenage bullies. Who would have guessed – indeed, predicted – that any filmmaker might develop the self-awareness to know exactly where to take this story without tipping the audience off or sabotaging their interest? “It was just a paycheck when I took it on,” Carpenter once said in a book-length interview about his career. That was a payday well-earned, and now long after the horror movie market has been saturated by sub-par adaptations of most of Stephen King’s famous stories, his end result is widely seen as one of the more effective screen treatments of the era, however corny or preposterous it may remain on paper.

Wednesday, June 19, 2019

Dark Phoenix / *1/2 (2019)

It takes a certain endurance to thrive among the X-Men, especially in the movies. Reflect for a moment on how frequently this team of misfits changes lineup: one minute a certain character is front and center, joining the ranks of Xavier’s mutants as their power comes to fruition, and then the next they are cast as a backdrop when someone more exciting (or dangerous) comes strolling through the doors, like new car models or better generations of cellphones. Only the more showy or idiosyncratic personalities ever make it past this curse of a momentary observation, and as with the source material the film adaptations have often leaned towards the same series of faces to revolve around: Wolverine (who even starred in his own trilogy of movies), Magneto (the most consistent villain), and Mystique (who has the benefit of, well, always being able to change her appearance). Now the filmmakers can add poor Jean Grey to that list of primary identities, if for no other reason than because of what her history will dictate: that she will go beyond being a normal telepath and see her mutant abilities ascend into the realms of gods and monsters. The newest chapter of this series, “Dark Phoenix,” has the distinction of casting her in that role before she is emotionally developed, which adds another challenge: how do you control yourself in a situation where everyone in the room has either lied to you or knows you must be destroyed to preserve humanity?

Wednesday, June 12, 2019

Last Tango in Paris / **** (1972)

No other high-profile actor from the Hollywood golden age was more earnest in personifying the agony of character than the great Marlon Brando. Across four decades of challenging performances that involved smooth-talking creeps (“A Streetcar Named Desire”), crime world kingpins (“The Godfather”), exiled military generals (“Apocalypse Now”) and a mournful dock worker (“On the Waterfront”), it was his harrowing turn as a pseudo-predatory widow in “Last Tango in Paris” that ricocheted with the most realism. Something within what was otherwise accepted as perfunctory dialogue and staple behaviors slipped past the notion of simple observation and echoed deeply and sincerely, particular in a cluster of scenes where the camera observes his mourning process. “I’ll never understand the truth about you,” he tells the figure of his deceased wife before collapsing in a heap of raw emotion over her corpse. There is the moment where the entirety of his career can be absorbed in miniature, in a scene where all the conviction of his method is unleashed in a heartbreaking explosion of grief and confusion. How did he find the ability, or the strength, to transcend the notion of embodiment and become the very source of torment he was portraying? Where most actors simply repeat the words and actions to the service of a story, Brando became one with an identity.

Tuesday, May 28, 2019

Zelig / ***1/2 (1983)

Over a period of four years in the middle of his lauded creative boom, Woody Allen assembled the pieces of what would become “Zelig,” a faux biography about a man from the early 20th century who could physically change his appearance just by being in the company of others with similar attributes. At the time, the ambitious artifice was merely regarded as a self-contained display of his comic ability, a closed world of the sorts of wisdom and quirk than often ran unrestrained in his more mainstream endeavors. Looking back on it now, however, one uncovers a deeper meaning, particularly when we use the full hindsight of his career as the framework. Like the enigmatic Leonard Zelig, Allen harbored deep questions about his own value that were frequently sidelined in an attempt to “fit in” with the world’s perceptions, and making movies – much like changing identities – became an outlet to work through the impulses and behaviors. If the sum of his career can be seen as a series of destinations on a road to that discovery, then his strange, off-the-cuff “mockumentary” provides the most unlikely roadmap.

Wednesday, May 8, 2019

Under the Silver Lake / * (2019)

Early on in “Under the Silver Lake,” Andrew Garfield offers the first of what turns out to be countless stares of confusion, as he gets caught up in a mystery that lacks all obvious conclusions. It turns out his gaze will reflect the inevitable response of the audience observing him. That is not to say they will share the same intrigue or dedication to the cause, mind you, but instead will discover themselves trapped in an agonizing web of deceit that tests the very patience of their commitment. For what, you may be curious? Consider this scenario. Garfield plays a Los Angeles 20-something, wandering from one sensory experience to the next, who befriends a beautiful blonde woman living nearby. Then she mysteriously disappears – along with all her belongings – the morning after they share some innocent flirtation. Possessed by a suspicion that she vanished as a result of foul play, his journey to find her takes him into a maze of controversies, conspiracies, false leads, lurid fantasy, violence, death, long-winded monologues, inconclusive solutions, absurd puzzles, hidden messages, and virtually every possible detective device every utilized in a movie. That it is all made with a remarkably sense of craftsmanship only adds to the offense; this is an endeavor so overwrought, so obsessed with tossing the proverbial rug of chance out the window, that it never deserves the aesthetic of the man orchestrating it.

Friday, April 19, 2019

Movie 43 / 1/2* (2013)

It is impossible to write anything disparaging enough about “Movie 43” to disrupt the notoriety underlying it. Here is a film – if you can call it one – that stands against its criticisms with an almost agonizing immunity, like a virus adapting to severe shifts in temperature or climate. And while countless writers and film enthusiasts have slung ambitious piles of mud without qualm for well over six years, with some still calling it the worst major release of the 21st century, the general public continues to give it the sort of life generally reserved for the more obvious failures like “The Room” or “Troll 2,” which endure as cult hits in late-night revivals. Yet to hear a basic description or run-through of the premise does not suggest just how ambitiously the material goes off the rails. It essentially plays like a series of amateur pranks you would find in a YouTube playlist. To observe them in a full-fledged composition, however, is to sense a marvelous lapse in judgment on part of Hollywood agents, who have set their bosses – actors and filmmakers alike – adrift in an artistic whirlpool. So awful is the experience, so utterly perplexing and tone-deaf is the payoff, that you have no choice but to watch on with curious eyes while your jaw falls depressingly to the floor. By the end you can’t entirely be sure whether you have watched a film or participated in a eulogy for the careers of its participants.

Tuesday, April 16, 2019

Us / *** (2019)

For well over three-fourths of its tenure, Jordan Peele’s “Us” moves to a rhythm that casts doubt on the momentum of its characters. Questions emerge through a rolodex of possible outcomes for nearly every intricate twist: are these people living in the hell that they have been ensnared by, or is it all part of a psychotic state forced upon them by something too baffling to deal with directly? Answers eventually become critical, as they must, but not before the very nature of individuals is tested in what seems like rip in the continuum; they move through a nightmare that tests them beyond the rules of their existence, as if their very existence has been an elaborate façade cloaking a collapsed reality. There’s a great deal of possibility in that prospect, especially for Peele, whose own “Get Out” also visualized a subterranean dimension while underlining powerful social commentary. But here the fun ends just as abruptly as it begins, in a final explanation so painfully broad that it inspires confusion more than closure. There is no question in anyone’s mind that Peele is slowly emerging as one of the most exciting provocateurs of modern horror films, but is a picture like this not more rewarding when the riddle doesn’t inspire our collective scorn?

Friday, April 5, 2019

The Head Hunter / *** (2019)

“The Head Hunter” is a creature feature in which the most fearsome beast is man himself, set adrift in a moral wasteland, where civilized behaviors are seized by carnal urges running wild in a horrific wilderness. The first scene establishes his routine while simultaneously pointing to the undercurrent of his vengeful demeanor; as he wanders past the frame to slaughter an unseen villain (we only hear the impact of the sword and the cry of a creature), a small voice calls him back towards his prior location. It is his young daughter, concealed in a tent, needing to know her protector is nearby. They exchange smiles and she returns to sleep, but the morose voiceover indicates this is a memory from the past; one of the beasts has apparently killed her, and now his life has become a long hunt for the animal responsible for her demise. In the meantime, the main wall of his cabin becomes a monument to all the heads he has collected – some frightening, others bizarre, few of them based in any tangible reality. The first reaction is one of befuddlement: what possible villain could be more dangerous, especially when his domicile already looks like a scrapbook of the most diabolical movie monsters you have never seen?

Thursday, April 4, 2019

Climax / ***1/2 (2018)

Some movies announce themselves in celebratory spectacles. Gaspar Noé’s “Climax” lands in a howl of agony. Born from within a creative engine that relishes the pain it inflicts, here is the culmination of the director’s most masochistic instincts: a laboratory of excess that unknowingly becomes a living hell for all the unfortunate characters populating it. How strangely challenging it must have been for him to look at this material and find the desire to exceed his own trajectory. After “Irreversible,” containing the most painful rape sequence ever made, and “Enter the Void,” a visceral exercise that sickened (literally) many members of his audience, the chutzpah underlining his strange career seemed poised to linger in the corners, unable to escape into something more daring. But now he has orchestrated a work of genius that upstages all the unsettling rhythms that came before, essentially because he has now married the lurid tendencies of his style with an arc that is profoundly engrossing. These are people whom we share little common interests, yet who transition from one extreme to the next as if holding us hostage through a rapid descent.

Wednesday, March 27, 2019

Transit / **** (2019)

Well before the nomadic lead character in “Transit” lodges a place in our understanding, the movie observes him in a grind more akin to that of a noir protagonist: always in the wrong place at the wrong time. This trend is established in the first scene, during a dialogue exchange in which he is persuaded to deliver letters to an enigmatic source for a monetary reward. The situation: a provocative writer is in hiding as the German occupation nears Paris, and it would make more sense for a stranger to show up at his hotel carrying parcels than a known rebel who might attract the wrong attention. The letters, we learn, consist of information that would allow him to leave France (one indicates he has a wife beckoning him to meet her in Marseilles). On arrival at his room, however, he discovers the writer has committed suicide in the bathtub, leaving behind an unfinished manuscript (among other things) that he is compelled to take. And so he returns to the streets, now aimless as the Germans move in towards frightened immigrants, with no established identity to defend him… other than that of his deceased source, whose passport he has chosen to safeguard. After stowing away on a train with a wounded friend and narrowly escaping inspection, he arrives at the port and is mistaken for the deceased scribe, leading to a moral quandary: can his conscience allow him to play along in order to escape the fascists? Or will the arrival of a strange beautiful woman complicate the matter further, especially when he discovers that she is the wife of the man he is impersonating?

Tuesday, March 12, 2019

The Hole in the Ground / ** (2019)

Some horror movies are content to let the terror sneak up on you. Others may show the characters wander into it almost blindly, usually compelled by the dramatic currents of grief or curiosity. A rare few will jump head-first into the danger, because without fully understanding motives or behaviors first, we can resent a film for not providing adequate breathing time to lodge anything into a plausible context. “The Hole in the Ground” shows a new director audaciously planting himself in the third distinction, where he sets himself up for a plethora of narrative dilemmas by, basically, skipping over the development of his would-be victims. The key moment: a mother and her son are driving in the wilderness and nearly run down an old woman standing aimlessly in the road, her withered face concealed behind a dark robe. Briefly, after being checked on by the concerned driver, she turns towards the vehicle and catches a glimpse of the boy. The soundtrack emphasizes the impulse, indicating something ominous. What does it indicate? How will it affect the ones who nearly ran her down? These are questions that ought to be reserved for a time after reaching comfort with the important players, who are clearly likable but seem displaced by a melancholy that never has a chance to formulate. In the age of genre pictures that often make their points in overlong passages, here is one that trims off too much and shoehorns it into a space too brief to allow for an adequate understanding.

Wednesday, March 6, 2019

The Happytime Murders / * (2018)

Aren’t we well beyond the point of an idea this absurd? Isn’t there someone, somewhere, high up in the studio system who looks at the mere concept of a movie like this and is willing to ask, “hey, is it really that appealing for moviegoers to show up just to see puppets shouting obscenities and making awkward sex jokes for 90 minutes?” “The Happytime Murders” has the dubious distinction of being the most miscalculated idea for a film in many a moon, a sham of a concept saddled somewhere between obvious and juvenile, with the right mix of desperation thrown in for good measure. That would be all but a minor inconvenience, had it not also been one of the most unfunny comedies of recent years – but by coming across as such, the idea warrants the outright resentment of any who dare experience it. Dwell for a moment on the fact that a director with a background in this genre, two established writers, over a dozen well-known producers and countless talented men and women stood behind the scenes and actually put conscious effort into the material – how were so many willing to be freely associated with a movie that was doomed to unravel their credibility in 90 minutes of laughless, mean-spirited hogwash? The more ambitious onlookers might, I suppose, find entertainment in imagining how disastrous the early story conferences were, or if anyone sitting at the table was conscious long enough to wonder whether they were too caught up in cynicism to sense their integrity slipping.

Wednesday, February 27, 2019

"American Beauty" Revisited

Like the French Algerian Meursault and Holden Caufield after him, the character of Lester Burnham has soared above the peak of lively resentment and been canonized as one of the great antiheroes of modern pop culture. His presence in “American Beauty” plays to the ongoing call for the everyman’s rejection of procedure, which has been necessitated by the steady decline of the modern workforce in a culture that imprisons them in cubicles and conforms their thoughts to a script of faux courtesy. Traces of that distinction were first visible in the comedy “Office Space,” released in the same year, but this was the moment where the ideology found its most unflinching force: a man whose brutal honesty felt like a nudge towards obliterating the conventional wisdom. Consider how much of the film about him involves the silent bewilderment of supporting players, right down to a wife and daughter who can only look on, in stunned silence, while a pathetic shell of a man suddenly discovers his voice. Perhaps they are surprised to find he still has a spine. Perhaps they are mourning the inability to continue using him as a scapegoat. Or maybe it’s because they can no longer see beyond the ceiling of what he is gradually tearing down.

Tuesday, February 19, 2019

Bohemian Rhapsody / *** (2018)

“Bohemian Rhapsody” is a biopic that is more resonant in theory than in practice, a study of Freddie Mercury that seems like it was filmed after its director and writer researched their subject over one brief afternoon on Wikipedia. What a shame it comes to this – that after years of false starts and changing casting decisions and ambitious goals, a film about one of the most profound entertainers of his time is barely motivated to offer the basic outline of his journey, much less a few precious insights. For a good while, it appears to be going somewhere: a series of early scenes feature the avid and gifted Mercury (played here with precision by Rami Malek) charm his way into a job as a college band’s lead singer, push them towards big gigs, master a distinct sense of showmanship on stage and even negotiate the band’s future in a record deal with significant creative control. Yet as the scenes pass and the camera peers into recording sessions to catch a glimpse of their intricate creative process, we begin to sense a distinct absence of a group dynamic. Their dramatic interest is curiously muted. Does that not, in itself, contradict the very nature of the Mercury persona, who moved as if guided by magic on stage while guarding over deep and meaningful relationships, including those with his bandmates, behind the scenes?

Wednesday, February 13, 2019

The Emoji Movie / * (2017)

Imagine, if you will, a world in which images on a cellphone screen secretly possess free will. They don’t so much exist as they consciously regard themselves as tools in a grand purpose, which involves competing for popularity against those who are either eccentric or unconventional. By the most basic principle of an outline, what goes on in their small world is the equivalent the modern high school social structure – all about cliques and illusions instead of any sense of individualism. That makes it rough for anyone attempting to break free of that monotony, but teenagers at least have an outlet: those constraints come to an end after four years. What of the poor helpless beings that populate “The Emoji Movie,” who are resigned to live an unending existence of tedium for the sake of keeping pace with the demands of their owner’s anxious trigger fingers? What happens if someone can’t conform to the expectation? A conflict ensues when one of them shows emotions he ought not to be programmed with, leading to a suggested malfunction that could potentially destroy them all in a massive hard drive reboot. But if that will erase everything, including them, then why has no one bothered to inform them that most cellphones tend to die out after a three-year stint anyway?

Sunday, February 10, 2019

You Were Never Really Here / ***1/2 (2018)

If most modern films consciously exploit a spiritual link to the past, then “You Were Never Really Here” shares its most fundamental detail with the great “Taxi Driver.” Both are stories in which men weather the curse of exhaustive past traumas, all the while using them to mask a brooding contempt for civilization. In relation to these worldviews, each sees children as victims of a corrupt paradigm that must be dismantled, be it through activism or slaughter. The conflicted antihero of Scorsese’s film kept the company of a young teenage prostitute as motivation to pick up arms and become her protector, and now comes Joe, played by Joaquin Phoenix, a loner who is hired by others to save teenage girls from human trafficking, and then murder their enslavers. At first the routine seems too coarse and vulgar, even in the framework of a film saturated in nihilism, but a thoughtful picture becomes clearer with each passing sequence: this is a man who was exposed to violence when he was too young to process it, and the psychological wound it created is more easily soothed through vengeance for the innocent.

Thursday, January 31, 2019

Sleepaway Camp III: Teenage Wasteland / * (1989)

It appears, quite likely, that I have simply misinterpreted the bloody jaunts orchestrated by one Angela Baker. After two movies in which we see her do away with nearly all her peers, usually in moments where awkward posture emphasizes her meek stature next to victims that otherwise ought to be able to overpower the situation, a reader has wisely chimed in that she may have just been kidding the whole time. “These movies are supposed to be funny!”, he confesses. Ok, let’s go with that for the sake of moving through “Sleepaway Camp III,” which occurs one year after the events of the previous, when the community seems to still permeate the stigma of tragedy. Yes, it is entirely possible to view the fact that this year’s roster of participants camping on the same grounds as the previous murders is hilarious – after all, who would be stupid enough to really allow the possibility, especially knowing that the culprit was still at large? Or how about the fact that the camp counselors function less like authorities and more like clueless caricatures, unwise to Angela’s mayhem until they are staring back at her instruments of death? How about that whopper of a development of a supporting player named Barney, who is actually a cop, and the father of a son who was beheaded by Angela the year prior? Normally we would assume he is there to be a protector to those who might face repeating history, but those clever old writers have stumped us; he doesn’t realize she is back on campgrounds until staring at the loaded end of a gun. What a romp of a good time all of us could have had, if we knew from the start that this was done with a tongue firmly planted in the filmmaker’s cheek!

Tuesday, January 29, 2019

Sleepaway Camp II: Unhappy Campers / 1/2* (1988)

The title alone inspires more thought than anything occurring on screen. What do these campers have to be unhappy about, you might ask? Are the would-be victims of yet another massacre in the great outdoors as miserable as the first warning insists? If so, what is the source of their discontent? Could it be they are dejected because all their friends start randomly disappearing? Not really, as that does little to affect their routine. Are they angered by the overzealous discipline instilled on them by a camp counsellor who treats them like infants? Hardly; her tactics provide the fuel for their own consistent rebellion. Are they just generally depressed? Not at all, otherwise they wouldn’t banter with one another like teenagers at a frat party for nearly every scene they occupy. No, these people are in total bliss of what they are doing, ignorant of what is coming for them. So what is it that constitutes that strange insinuation? I have a theory it’s an in-joke for the actors, all of whom look uncomfortable reciting inane dialogue while they are provided awkward overlapping speaking cues. That is the least of their worries. Unfortunately, by the time something strange or foreboding makes itself known to any of them, they are all in situations in which they will be murdered by someone with a strange axe to grind, usually before there is a chance to react. The real unhappy ones should be the audience: not only does the film contain no mystery or buildup, it reveals the face of the murderer before the opening credits have rolled.

Wednesday, January 23, 2019

Mary Poppins Returns / ***1/2 (2018)

Long ago in the alcoves of the purest childhood memories, a charming nanny fell from the sky over England and became a lynchpin for the ambitious daydreams of young moviegoers. Although five decades have come and gone since “Mary Poppins” instilled that impression and captivated many a heart, rarely does she escape the notice of those in the recent generations, who have stockpiled their own experiences as the film endures across all the traditional time barriers. It was perhaps always inevitable, therefore, that the legend would eventually inspire thoughts of a follow-up, especially given how eager the Disney brand is to repeat its own history. And now in the midst of a parade of live-action remakes and reboots comes “Mary Poppins Returns,” in which we are presented the opportunity to spend another two colorful hours in the company of an unassuming caregiver who whisks her subjects into the world of elaborate musical fantasy. It goes without saying that there was little possibility of anyone besting the great adventures of the first film, but the good news is that even cynics of this formula will leave the theater feeling thankful for the chance to engage with a delightful spectacle rather than a pointless retread.

Tuesday, January 15, 2019

Dogtooth / ***1/2 (2009)

There is no easy entry point for those fascinated by the world Yorgos Lanthimos creates in “Dogtooth,” but the impenetrable nature of the material burns through our curiosity like a hot knife cutting through margarine. Here is where the very heart of the director’s well-known panache for elaborate absurdism drew its first beat, in a story of a family so far removed from the civilized world that they could very well be existing on a sound stage. Sometimes that even seems like a legitimate possibility, particularly as we attempt to pigeonhole the plot details through our knowledge of film convention; there are scenes modulated as if they are hinting at something grandiose, like a great reveal just waiting to be uncovered. Our mistake, and therefore his asset, is assuming this all leads to some sort of payoff. This is a movie that demands us to simply observe, contemplate and react without riding any of the traditional waves. There are no reveals, no sudden twists of fate beckoning us on towards a detail highlighting the literal context. And to show any patience with whatever endurance test drives these characters, we are asked to accept them not as fully realized people roused by curiosity, but as experiments comfortable with their cultural isolation.

Tuesday, January 8, 2019

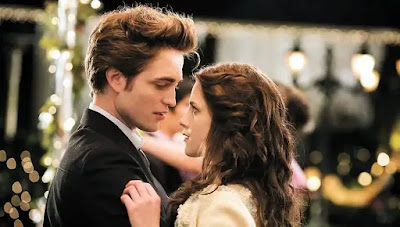

Twilight / *1/2 (2008)

Vampires rarely require the companionship of fearless dupes to function as predators, but it certainly changes up the monotony of an exhausting routine. Luckily for one featured in “Twilight,” he makes the company of a teenage girl who audaciously regards him as an equal. Maybe that’s part of what cripples the movie surrounding them: it misconstrues the dynamic that is otherwise fundamental. These are not unions established by conflicted beasts and ambivalent humans, but by souls who find that their alienation is one helluva common interest to flirt over. Sometimes, they even share in the same sense of hormonal desire – hers new and emerging, his apparently immune to hundreds of years of undeath. They circle around the point until there is no way to avoid the inevitable: their awkward exchanges and forceful outbursts are a mechanism standing in for eventual foreplay. That might have worked in a film that had any sense of what characters were about beyond their need to touch the forbidden, but like most great psychological lessons in the hands of novices, this is a story far more interested in dancing to rhythms than understanding melody.

Monday, January 7, 2019

Hell House LLC 2: The Abaddon Hotel / ** (2018)

When a novice filmmaker exceeds the restrictions of a formula, he proves he may have a talent. When he unsuccessfully attempts the challenge a second time, one wonders if that talent may have just been dumb luck. That becomes the point of consideration throughout the course of “Hell House LLC 2: The Abaddon Hotel,” a sequel that has more questionable distinctions than just a convoluted title. The contrast is made more obvious by how young Stephen Cognetti contradicts the simplicity of his first endeavor, a film that, you may recall, used no CGI and generated monumental scares from camera angles, editing tricks and convincing performances. By most estimations it was a terrific little movie that harbored all the necessities of quality horror. But now he and a new cast of unknowns has been overtaken by the need to stuff a follow-up with laborious explanations, one-note acting, countless subplots involving paranormal experts and one-off viral sensations, confusing shifts between timelines and a final reveal that destroys whatever mystique is left in the premise. If our first trip through the notorious Hell House was wrought with thrilling dangers, here is a reminder that going back is rarely worth the price of admission.

Friday, January 4, 2019

Hell House, LLC / **** (2015)

The story goes, as it must, through the grinder of utterly dependable formula: a terrible and inexplicable event occurs to people, and years later the footage of the victims winds up in the hands of mystified onlookers. This is the initial pitch made by “Hell House, LLC,” yet another entry into the “found footage” division of horror films, where the accounts of would-be victims are well-documented by the cameras they hold. This time, the prey has abandoned notions of searching for vengeful witches or spiritual hauntings and have come to, basically, document something less ominous – that is, putting together a local Halloween attraction in Abaddon, New York. Unbeknownst to them, alas, the abandoned hotel that comes to be the site of their frightful venture is more than just dark rooms filled with strange noises and creaking floorboards. It seems to permeate some sort of threatening energy. Sometimes, the viewing lens will even spy this possibility – shadows in corners, symbols etched on the basement walls, figures moving through doorways, and Halloween props that move entirely on their own. Did they bring some sore of malevolence in there with them, or was it always there, lying dormant? Some wisely suggest leaving behind the project, but one stubborn proprietor refuses, leading to a chaotic and frightening opening night in which 15 people pay with their lives, including most of the original managers.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)