Within the myriad of downbeat human experiences attached to the movies in the past twelve months, none was more heartbreaking than the loss of a Hollywood clown. On the day that Robin Williams was found dead of suicide, unrelated lives seemed to collectively unite in a pass of grief that also served to highlight the tragedy of the times: not only were we all inching ever so closer to the gates of mortality, but the journey towards it was losing its comic edge. His loss was echoed just a mere month later when Joan Rivers also passed on, and the conscious acknowledgment that we are now growing older in a world without either of them seems to create unnecessary shadows in peripheral hindsight.

Sunday, December 28, 2014

Monday, December 22, 2014

Lessons from Criterion:

"White Dog" by Samuel Fuller

The sudden entrance of a majestic white German Shephard in the first minutes of “White Dog” at first seems like a drastic respite in the life pattern of a simple but struggling movie actress. She leads the kind of detached existence ordinarily reserved in the movies for those boring office secretaries everyone always overlooks – complacent, dead-end and almost suffocating in the paralyzing grind of a day – but when this animal aimlessly wanders into the road and is hit by her car, a necessity rises within her heart to become his surrogate owner and protector. What for? Guilt is not the isolated emotion. Early observations emphasize traits of a loyal companion; he is attentive and eager, and in a perilous moment when a rapist breaks into her house on the hill and attacks her, the determined canine leaps into action as if her self-appointed protector. Though theirs is a connection roused from accidental circumstances, it is as true to the essence of the human/pet dynamic as any of our own positive experiences with our trusted four-legged friends. But then there is a moment where the image is shattered quite drastically, and the movie enlists a harmonic implication so sobering that it doubles as a very critical psychological revelation – for us, for the characters, and certainly for any viewer reckless enough to make a knee-jerk assumption that the material might deviate into the foray of Stephen King-style antics.

Friday, December 19, 2014

Weathering the Storm

Was it just a minor coincidence that a downtrodden movie like “Gremlins” crept back into my awareness at the onset of the holiday season? Were there indeed universal energies that acted as a gravity in pulling my notice towards a film so clearly about the brutal shattering of lighthearted nostalgia? Just as the reality of adulthood acts as a decaying influence on the recesses of our youthful memories, so do the movies remind us that the innocence in all things must, yes, come to an abrupt end. That is not cynicism; that is reality. And as overpowering as the silliness may be in a story about gremlins that terrorize a small town at the onset of Christmas cheer, it nonetheless mirrors a universal sentiment in those scarred by the blast: we don’t get any younger, and fate does not get any kinder.

Monday, December 15, 2014

The Forbidden Dance / 1/2* (1990)

“The Forbidden Dance” is the most unpleasant dance movie ever assembled, a film that defies all sense of merit by intercutting an endless array of pelvis gyrations and Latin-inspired grooves with a tone so inconsistent and downtrodden that it left me wincing in discomfort. As an experiment of genre sensibilities that follows the successes of “Dirty Dancing” and “Footloose,” the movie also undercuts the formula with even more offensive impulses – namely, the opportunity to use the one-note setup as a mask for pushing a shameless political agenda, and a rather flimsy defense of one at that. What were these filmmakers thinking? Were they genuinely concerned about the issues they raised beyond the ordinary dance movie clichés, or were they (as I suspect) simply using them to add phony dimensions to a premise of stunning simplicity? Their antics seem to be orchestrated by a hand of fate that constantly keeps one of its fingers on the bad taste trigger, and when the movie reaches a point where it forces us to endure a scene in which a scared South American native is leered over by a switchblade-wielding woman who encourages her to undress in a hallway while feigning voyeuristic pleasure, I wanted to scream out in protest.

Friday, December 12, 2014

The Hunger Games: Mockingjay Part 1 / *** (2014)

The early moments of the latest “Hunger Games” picture are about nightmares: specifically, those that belong to Katniss Everdeen, who often stirs from slumber in violent fashion as if escaping the clutches of a brutal adversary. The camera does not show too many details of their content, and that’s remarkable given the nature of our cinema to reveal the most gruesome aspects of our imaginations; instead, the scenes are used to cast underlying vulnerability on a character that must become the face of an impending revolt, and her uncertainty drives the direction of a wide array of critical decisions leading up to an agenda that will (hopefully) overthrow a bunch of overdressed fascists from power. Our inability to observe the entirety of those dreams is irrelevant; because they are hers and hers alone, they add a touch of almost emotional mystery to the material. Indeed, what is left for her to fear, especially in a society content to sacrifice kids for the sake of entertainment? Is there really anything remaining that could compare to the tragedy of participating in not one but two battles to the death with a bunch of innocent peers? Hers is the trauma that often turns the youngest of minds into the most cynical, and if there is to be any relief at the end of this gloomy world of death and oppression, one hopes she is able to reconcile some of it before drowning in the inevitable depression that follows.

Sunday, December 7, 2014

Gremlins / *** (1984)

Childhood joys often settle in the eyes of little fluffy creatures that capture our hearts, and for me no greater instrument for such possibilities resonated more than a small gremlin named Gizmo. As a child of the ‘80s, there were certainly ample opportunities to find comfort in the company of sympathetic movie creations – including Spielberg’s famous E.T. and George Lucas’ misunderstood Ewoks – but something about a cute furry beast with long ears and big brown eyes bypassed all others as a source of visual comfort. To me, he embodied every trait necessary in creating youthful wonder: innocence, clumsiness, fear of the unknown and a certain gutsiness that spilled over when a plot insisted a level of danger onto those he cared about. The adorable factor was the most minor of those facets but no less critical, and when one brought all of those qualities together in the figure of something so delightfully endearing, there was scarcely a moment where we could walk away from the experience not wishing he was real (or better yet, actually part of our lives). And that’s the truth even after one acknowledges the bizarre anatomical characteristics he comes cursed with.

Thursday, December 4, 2014

Birdman / ***1/2 (2014)

To separate Michael Keaton from his performance in “Birdman” would be to undermine an essential insight into the parallels of a shared existence. Much like the conflicted actor he plays, here is a movie star whose success in front of the camera was clearly diminished by the overreaching shadows of one prominent role in the distant past: that of a very popular screen superhero. For Keaton, that came in the form of Batman; for Riggan (the man he plays), it was a giant avian crusader aptly named, well, Birdman. Throughout the course of events of the film, random eyes often meet Riggan not with respect or chemistry, but with an almost detached sense of nostalgic fascination; once upon a time this was a guy who was at the center of a very ambitious spectacle of costume and action, and few are able to separate the mask from the one who first wore it. So effortless are Keaton’s own subtle scoffs to these realities that one never wonders if they truly originate from a place of empathetic recognition. Some have said that to play a superhero in a movie forever damns you to the professional prison of the alter ego, and if that indeed rings true, than there is no denying that Keaton’s career trajectory is a textbook example of that unfortunate curse.

Saturday, November 29, 2014

A Streetcar Named Desire / **** (1951)

Vivien Leigh doesn’t so much step through a trail of locomotive steam as she emerges in a world of opposing values. The opening shots of Elia Kazan’s “A Streetcar Named Desire” expose this facet of truth almost without conscious insinuation; because the frame is occupied by that dreamy sense of certainty that often comes with evocative black-and-white photography, our eyes are quick to notate details that seem out of place with the formality of the material. Her arrival is placated by all the traditional verbal facets of narrative engagement (a moment in which a character asks for directions while at a train station was often a staple of these sorts of movies, for example), but when she waltzes into the dimly-lit French quarter of New Orleans searching for her sister, the first memory imprint is that of streets littered in trash, and nameless onlookers that seem to be past the point of simple intoxication. While such visualizations were the stuff of those well-kept secret corners of mainstream society – at least according to the naïve historians – they had scarcely been used in the movies by that point, and never to such a blatant degree of honesty.

Monday, November 24, 2014

Showgirls / **1/2 (1995)

When Nomi Malone marches right into the early moments of “Showgirls” dressed like a rejected stand-in at a music video shoot, it becomes the first in a long list of our observations that inspire laughter. No, not the kind that is intentional or even self-aware; this is one of countless moments that warrants unexpected chuckles based on an underlying absurdity. That the movie is not even supposed to be a comedy marks it as something of a myopic miscalculation; under the well-known influence of writer Joe Eszterhas and director Paul Verhoeven, what we observe was, in truth, once considered a genuine character drama in the hands of people dedicated enough to the work to supply it with a sense of production value. Perhaps the notion that it was all supposed to be serious was very well sold as a ploy to all those in front of the camera, but who could possibly imagine anyone behind the scenes finding sincerity in this? Who could believe that Eszterhas’ story, a tone-deaf journey through absurd female sex fantasies, had hope of being passable, much less erotic or stimulating? Here is the portrait of a woman displaced from all sense of grace and modulation, who leaves behind the unknown realities of her past and walks brazenly into the bright lights of Las Vegas with a goal to become just another object in a long line of mediocre topless dancers.

Sunday, November 23, 2014

The Hunger Games: Catching Fire / ***1/2 (2013)

There are few greater pleasures than one’s own reservations being abolished by the reveal of a genuine purpose. “The Hunger Games: Catching Fire” is that rare sequel that not only surpasses its original but also brings with it the undeniable sense that yes, finally, all the maddening chaos and underlying pathos of this deeply political story has finally revealed an important subtext. I admire it not just as an entertainment but as a persuasive statement against suggestive themes, and because it sets these ideas within an intricate world shrouded in unending gloom, those arguments are enriched beyond the knee-jerk assertion that they simply exist to create doubt in the survivability of young heroes. So often in the structure of modern adult yarns do storytellers depend on the cynical reality of some unimaginable near-future to stir the hearts of youthful adventurers into rebellious actions, and often without a plausible backdrop. This is a series that has always been well made and seemingly within an identifiable frame of reference, and yet now seems to be more than just a denial of hopeful outcomes. “Catching Fire” supplies its likeable heroes with a discernible presence that enriches the groundwork, formulates a plausible direction, engages the characters and gets us all genuinely involved without squandering our sense of hope.

Thursday, November 20, 2014

Mike Nichols, 1931 - 2014

The instinct to lead usually rises to the surface in the presence of new opportunities. For the brilliant Mike Nichols, that opportunity came in the form of a then-relatively unknown stage play called “Barefoot in the Park.” When he was handed the rights of the all-important director role for that new stage arrival in 1963 – early on in his extensive Broadway career, no less – he was marveled so tremendously by the influential connotations of the job that it informed his instincts for most of his life, at first with theater productions and then, ultimately, the movies. As revered as he was in the course of his stage career, the cinema is where his passions developed into something of remarkable profundity, and today we often cite a handful of his pictures as not just well-made undertakings but also vivid extensions of our most precious memories.

Saturday, November 15, 2014

Horns / * (2014)

“Horns” is a movie about a very unlucky guy who is accused of murdering his girlfriend, quickly cast down as a town pariah, and then wakes up one morning to discover two devilish horns growing out of his forehead without reason or explanation – although they do inspire everyone around to confide their deep dark thoughts. If only the audience were spared the exhausting nature of this mystifying predicament. Somewhere in the creative trenches of writer hell, I am sure there are filmmakers out there sifting through screenplays like this that are genuinely capable of funneling crazy material into something resembling a dedicated vision. But under the influence of director Alexandre Aja, what we get here is two hours of maddening, thoughtless exercise with misplaced assumptions; seeing it, one is left with the impression that all those involved were too committed by novelty in order to detect the necessity for some level of modulation. Indeed, an idea seeped in supernatural metaphors often requires a mind more honed into the mood of those implications in order to make them relatable to an interested viewer. This is the kind of movie that seems clobbered together under some sort of delusion that editing fixes all things, including a director’s detached sense of execution.

Thursday, November 13, 2014

The Goonies / **** (1985)

It was never just about a group of kids becoming active participants in endless swashbuckling adventure: they also had to be projections of all our relatable childhood insecurities. When Richard Donner utilized this element of suggestion during the making of “The Goonies,” that precious morsel of insight was so thoroughly concealed behind an endless display of kinetic action and ambitious visual energy that few (if any) moviegoers were observant enough to detect it; it was as if he and his writer Chris Columbus devised one of the most elaborate hidden agendas of their time. Because casual eyes are often more enamored by the presence of relentless fanfare when they go to the movies, imaginations were directly inspired here to heights vast enough to sense peripheral possibilities waiting outside the camera frame, and for well over two decades that sweeping sense of joy persisted in the minds of anyone who dared to recall the great possibilities of youthful escapades. But when wonder fades from the senses and is replaced by the sting of individual being, what point does a movie about a gathering of silly kids searching for a pirate treasure have to say?

Tuesday, November 11, 2014

Bad Johnson / 1/2* (2014)

Nothing gets a man in trouble quite as often (or as severely) as his penis. While some members of the male species have successfully mastered that ever-so-daunting task of taming the mischievous trouser beast in all things sexual or romantic, countless others have allowed it to roam free and wreak havoc just about everywhere it goes without regard to consequence. The source of the problem is, I suspect, a linkage failure between anatomical functions; because neither the brain nor the groin are exactly eager to communicate with one another in such regards, they create perplexing gray areas in which destructive patterns often manifest. A good man will allow an enlightened mind to dictate his actions; a bad one will abandon reason and get caught up in the rush of a cheap thrill. And as always, there’s also those conflicted types – guys who indulge in the pleasures of the flesh but are conscious enough of their efforts to stand back and examine their place once it becomes apparent that their brash chutzpah is leading them down very unforgivable paths.

Saturday, November 8, 2014

Big Hero 6 / *** (2014)

Disney’s newest CGI cartoon, the comically-charged “Big Hero 6,” plays like a union of opposing sensibilities. In one regard, the movie’s use of high style and energy are stirred right from the same place of heart that inspired some of the most ambitious feature cartoons over the years: consistently colorful and filled to the brim with astounding sights, it emphasizes the continued prowess of computer animators who see their canvas as only the tipping point of total visualization of their imaginations. On the other hand, the narrative structure does not rise from that internal spark of traditional animated storytellers; instead, what we find on screen are the all-too-familiar mechanics of comic book storytelling, in which plucky adventure is fueled not by whimsy but by the deep-seeded notion that tragedy must befall an assemblage of characters in order to push them to the limits of their being. The primary hero of the picture, a science and robotics guru named Hiro, endures the obligatory journey of adolescence but is not caught in that whirlpool of simplified youth sentiments to make him easily identifiable to the youngest of audiences, and when there is a moment that requires him to stare down the source of his trauma and resort to a knee-jerk decision, he seems less like the hero of a cartoon and more like an early representation of a Bruce Wayne or Peter Parker.

Thursday, November 6, 2014

Gone Girl / **** (2014)

If the dark and moody “Seven” declared the arrival of an exciting film provocateur, then “Gone Girl” sees his audacity realized to the peak of possibility in the frames of one of the most fearless entertainments of recent memory. Under the guidance of the remarkable David Fincher, this is one of those rare, elusive endeavors that contains nearly every important quality I cherish about moviemaking: high enthusiasm, a sense of presence, unending energy, technical craftsmanship, devious performances, wicked chemistry and dialogue, and that all-important cognizance that allows its players to navigate an intricate psychological web with some level of premeditation. When one considers all these virtues within the frame of reference of a picture that takes some perverse pleasure in pulling as many rugs out from underneath the audience as possible, what we are left with also has the capability of inspiring some level of nostalgia: as a confident thriller that dodders between the macabre and the humorous, it beckons comparisons to the most delicious of Hitchcock’s classics. That’s almost as shocking a reality as it is a rewarding one. While studios are all about the tease and nothing about full realization in our present grind through 21st century cinema, at last here is a brilliant movie that knows manipulation is going on in nearly every pass of action, any yet never backs down from any of its many fearsome implications.

Friday, October 31, 2014

Lessons from Criterion:

"Peeping Tom" by Michael Powell

In a genre standard where the movie camera amplifies the often disparaging final moments of human life, recent films like “The Poughkeepsie Tapes” and “Captivity” seem like nothing more than faint echoes when held against the defining catalyst that is Michael Powell’s “Peeping Tom.” Initially regarded as one of the most dangerous films ever made – and shocking enough to effectively put its famous director on the unemployment line – it came and went in the early months of 1960 with startling fallout, and the controversy it inspired continues to haunt many of those associated with it. There is a knee-jerk curiosity surrounding its existence that perplexes movie historians to this day: how did a director of fairly straightforward films find the nerve to immerse himself into the dark nature of a story like this, and without any sense of restriction? Even now, his radical shift in reasoning plays like a dual curse; young eyes eroded by the visual excess of modern times may absorb its images without grasping their initial potency, but the story’s psychological implications continue to declare themselves profoundly on our rattled cores. So many movies about the most depraved of life-takers also function as therapies for their audiences; this one makes us accessories to deplorable deeds, and rejects all opportunities to find relief from them.

Thursday, October 30, 2014

House of 1000 Corpses / *1/2 (2003)

Rob Zombie’s “House of 1000 Corpses” is a movie by a man without any sense of modulation. The camera arrives in his possession like a discovery of unprecedented importance; standing behind it, the air of his enthusiasm seems to overflow with every sharp camera angle and quick edit that emerges from his zealous fingertips. For most first-time film directors, the opportunity to take one’s bizarre visual flair and incorporate it into the frames of a motion picture would be an opportunity worthy of some level of focus, however eccentric. Alas, here is a man so enamored by the notion that creative control has been passed to him that the end result lacks a central distinction, and meanders through five or six moods with extremely disconnected results. Somewhere underneath heaps of overwrought images and flashy cuts meant to, I guess, emphasize the schizophrenic nature of his screenplay (which he also wrote), traces of a viable filmmaker are aching to connect with encouraging audiences. Those who will herald his debut effort as some sort of profound revelation will not be picking my selections during late night horror movie marathons.

Sunday, October 26, 2014

Mama / *** (2013)

Two little girls are whisked away nervously by an anxious father in the early scenes of “Mama,” and after his car crashes into an embankment during a snowstorm, they become stranded in the woods where they wander into the murky halls of an abandoned shack nestled between withering trees. No one lives there upon close inspection, but the shadows seem to vibrate with a certain existential tension – as if some kind of ominous energy remains behind, implying silent threats. Unfortunately, the ensuing actions of the rattled father cause whatever is there to manifest in the form of a chilling ghost-like figure, and when his form is consumed and the girls are left behind to fend for themselves, they make a connection with the presence that will inform their growth over the next five years. Because each is no more than a couple years old at the time of their abandonment, age passes and isolation shapes them into feral, speechless creatures that walk around on four limbs – traits that are not easily breakable once the times comes for them to be integrated back into civilization. When their whereabouts are discovered and their uncle comes rushing to their rescue, in fact, there is almost no immediate connection between them: only vague remembrances buried behind primitive survival instincts.

Saturday, October 25, 2014

Captivity / zero stars (2007)

When it comes to the daunting task of dissecting the divisive nature of film genres, no kind is more volatile than the ever-so-audacious horror movie. What is it about the dark nature of the human psyche that fills filmmakers with such polarizing ideas? What is the tipping point at which any idea can lose sight of purpose and exist purely for the sake of senseless violence and mayhem? And moreover, how can the person standing behind a movie camera effectively balance the most lurid of notions with a context that validates their ideas, no matter how graphic? The more abrasive the material, the more difficult it is for someone at the helm to discover meaning. More often than not, it all simply falls into the hands of those who lack the foresight to stay within credible boundaries, or are just too lazy to try. For every effective endeavor that does in fact emerge from this genre, there are usually ten or twenty more of a similar vein that reject the concept of moral purpose. Roland Joffé’s “Captivity,” a despicable film, is the poster child for that latter sensibility.

Wednesday, October 22, 2014

30 Days of Night / ***1/2 (2007)

A small town in Northern Alaska surrounded by 80 miles of icy wilderness is about to see the last sunrise for an entire month. Residents of Barrow board up their houses and retreat south in order to escape the paralysis of a frigid landscape, but a few dozen remain behind – as caretakers of a dormant community, or as nomads enveloped in the solitude of off-the-grid survival. On the final day of sun, a fearsome-looking wanderer (Ben Foster) descends onto them with seemingly menacing intent; his rough exterior and threatening eyes shoot fearsome glances towards innocent bystanders, and his words are indicative of that ever-so-dependable sense of foreshadowing that often accompanies eccentric strangers in the movies: “That cold ain’t the weather – that’s death approaching.” Somehow it never dawns on any of those remaining that maybe, just maybe, a month of total isolation – and complete darkness – can be an instant invitation to destructive forces, especially those fearsome nocturnal monsters better known as vampires. You can’t really fault them, I suppose; out in the middle of nowhere and so removed from social norms, are people like this really apt to be well versed in the nihilistic philosophies of horror movies?

Thursday, October 16, 2014

Alien: Resurrection / *** (1997)

Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s “Alien: Resurrection” is not traditionally viewed as being anything beyond lighthearted science fiction entertainment, but its distinctive and quirky ensemble, clearly inspired by that of Cameron’s in “Aliens,” has had its own reverb effect on more recent team-oriented action films. Contrasting the formula established by three preceding outings in this series, here is a gathering of individuals whose underlying comical sensibilities are not, in fact, defense mechanisms against impending doom; instead, they exist for the sake of adding light to a mood, a sense of cheeky awareness to a tale so clearly saturated in unending bloodshed. When some of them turn up alive (and still gleefully untarnished) by the end of the picture, a critical perception has been shattered: death no longer has to be an inevitable conclusion for all associated with this premise, even though Ripley herself fell to it at the end of the third film (and still many more are killed throughout the running time here). But is that departure in sensibility at all surprising now, so many years later, when the nature of this genre has created the elbow room of added survivors beyond the one token smart guy who lives to become a launching device for sequels?

Monday, October 13, 2014

The Poughkeepsie Tapes / ** (2007)

Moviegoers who spend any length of time with “The Poughkeepsie Tapes” are not acting as mere viewers – they are eyewitness to the inner workings of a very loathsome madman. His identity remains a mystery to all those who have followed his trail for the better part of a decade, but their endless search for answers have yielded one of the most haunting discoveries in the history of criminal forensics: hundreds of video tapes in which the actual killer, acting as director, documents his spree of horrific mayhem. When the movie opens, this critical finding also comes equipped with an extensive arsenal of unanswered questions: how did a single human being brutally massacre so many people in upstate New York for such a lengthy period of time without getting caught? Who was he, and what drove his incessant pursuit for blood? And most importantly, what does his depravity reveal now in hindsight after hundreds of hours of footage reveal the nature of his insanity – a horrific portrait of a single person, or our collective ignorance in being able to stop his reign of terror? Just as the camera once served as a window into his menacing tendencies, now it is a confessional for legal authorities and relatives who must bargain with it in some unwavering hope to fathom – and even find peace with – the fallout.

Sunday, October 12, 2014

Burnt Offerings / ** (1976)

“Burnt Offerings” is one of those all-too-familiar movie detours through the doldrums of horror mediocrity, a film about a family of would-be caretakers who decide to leave behind the bright lights of the big city and spend the remains of their summer in the comforts of a charming countryside mansion that is being rented to them by, we gather, rather suspicious owners. Because they proceed to live in said property without the slightest awareness in the conventions of basic movie composition, that presents immediate disconnect in creating a relatable experience. What people in their right minds would so eagerly agree to submit themselves to such a shady arrangement given the nature of the scenario, which involves two elderly – and rather creepy – homeowners who insist on leaving their mother behind in an upstairs bedroom for the caretakers to look after? Did it not strike a mental chord in any of them that a cheap price tag for such a stunning mansion might involve rather ominous drawbacks? Even little kids would howl with pessimism at this kind of nearsighted narrative entrapment.

Wednesday, October 8, 2014

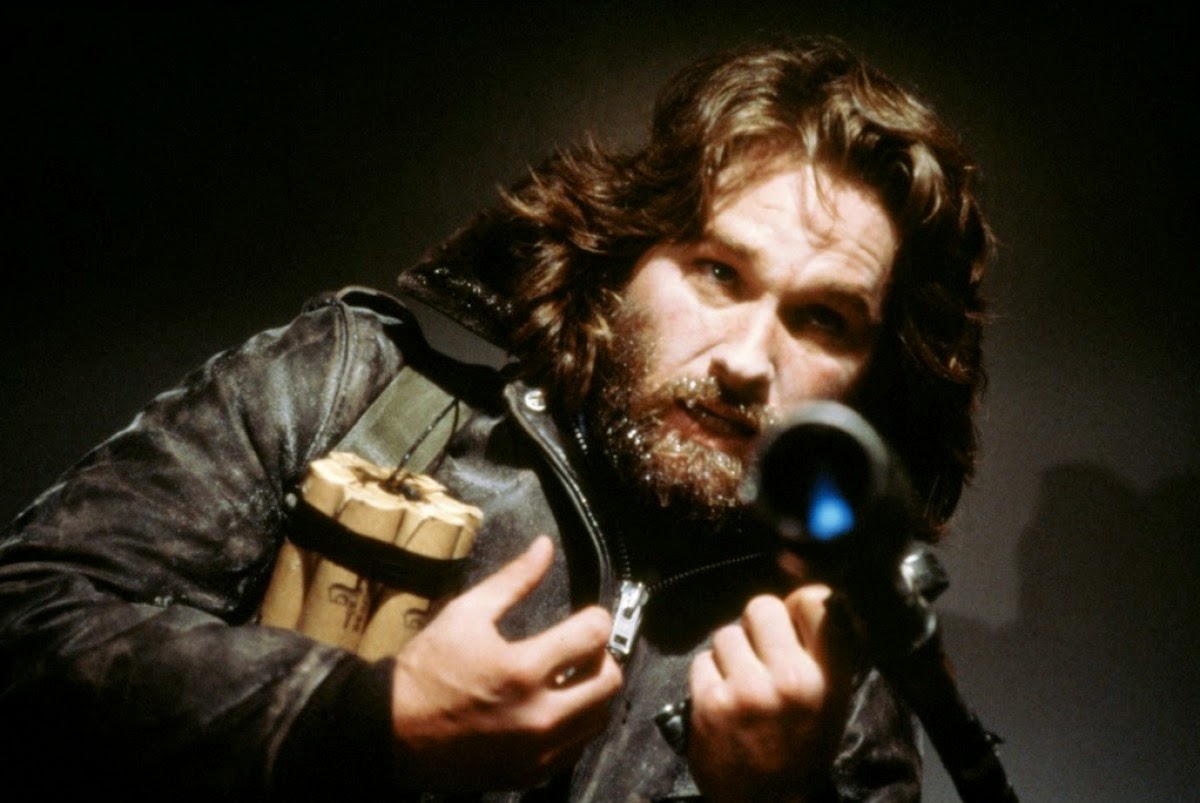

The Thing / *** (1982)

The story goes on and on through the reverb of the times: a trend dominates the output of the movies, and then along comes someone to louse the whole thing up. John Carpenter’s “The Thing,” about an alien life form wreaking havoc on a group of men trapped in a frigid landscape, is one of those beloved relics of the ‘80s that was considered the divisive game-changer for a genre in which premises like “Alien” had saturated the market with a relentless supply of bloodthirsty monsters jumping out from the shadows. Like a narrative sledgehammer, some would say it forever shattered the straightforward course of its cinematic family, and opened the sphere of possibilities up to much more horrific contemplations. Viewing the movie thirty years removed from that era, the ideas it presents are at least instantly distinctive; this is not a thriller in which ordinary beasts seek to destroy a gathering of unsuspecting victims, but one in which they take on the traits of Earthly organisms, absorb their DNA and walk among them as part of a convincing ruse to adapt to – and overtake – a new foreign environment. How unfortunate that the plot doesn’t know how to ride the wave as effectively as it should.

Tuesday, October 7, 2014

Devil / ***1/2 (2010)

The psychology of “Devil” offers such insightful and probing observations into the nature of evil that there is, at first, a desire to pause in cynical observation: what business does it all have being in a genre with such sensationalized standards? When it comes to the ever-so-exaggerated thrust of the satanic thriller formula, possibilities are usually reduced to over-the-top twaddle or flat-out silliness; there is seldom an inkling in anyone behind a movie camera to approach the subject with sensible faith, much less probing insights. Early narration in this movie is pitched like an audacious antithesis: because a critical observer in the ensuing events believes, wholeheartedly, in the old stories from childhood about the Devil’s looming influence in the world, it informs not only his perspective, but also ours. A good many questionable and horrific things occur to a selection of characters in isolation in just a short span of 80 minutes here – some of it mystifying, some of it disquieting – but none of it treads the line of implausible overkill, and the narrative deals with its horrors as conceivable facets that emerge from the grind of everyday life. And it’s also clever enough to stage the material so that all those involved share a deep-rooted commonality that unites them in their anguish. In one of many important scenes, as a police detective attempts to reason with the events while viewing them through security footage, he is offered prophetic words that seem to contrast his need for logical explanations: “there is a reason we are the audience.”

Monday, October 6, 2014

The Hills Have Eyes / ** (2006)

The geographical features referenced in the title of “The Hills Have Eyes” are a barren and desolate entity, scarred by fierce desert winds and intense sunlight that stretches miles upon miles in all directions. A truck carrying a trailer clobbers across the rugged terrain, carrying with it a family of California-bound passengers, who have little to no curiosity in the stories that these hills may or may not have to tell. Never does it dawn on them that the New Mexico landscape has been wounded by nuclear experiments and top-secret government tests; nor, for that matter, does anyone in the foreground get the sense that such tests have left behind rather menacing remains. Those hills tower over them like giant blankets of serenity, but the eyes of those ducking behind them are of a different kind, a different breed, a different intention. Had the protagonists known about these prospects before venturing into the area, no doubt they would have been eager to find themselves in an entirely different movie.

Sunday, October 5, 2014

A Nightmare on Elm Street / * (2010)

Maybe it is because I am so familiar with Wes Craven’s original “A Nightmare on Elm Street” – and all the ins and outs of its enduring legacy – that the modern remake of said film is at such an immediate disadvantage. Maybe the psychology of this idea was so potent that it carried on with vivid implications in the mind even now, negating the need to do a modern retelling. Or maybe, just maybe, opportunities to have an open mind are thwarted by the vulgar excess that permeates from the end result. Whatever rationale you take in with you, the new “Nightmare” film is definitely one of the more curious excursions through the excessive sensibilities of 21st-century horror movies. Produced by Michael Bay and directed by Samuel Bayer (the first feature film on his resume, no less), it replaces the fascinating context of Freddie Krueger’s existence with a seemingly endless exercise in violence and unrelenting pain. The fact that it does something so discouraging while still delivering effective production values goes to emphasize how misguided the genre’s architects have become in understanding what truly resonates in the eyes of their audiences.

Saturday, October 4, 2014

"A Nightmare on Elm Street" Revisited

“Here is a film that compares to some of the greats of the genre: a film that can be no closer to reality; a film that matches us against our true fears. No, there has never been a movie like it, and there never will be.” – taken from the original Cinemaphile review of “A Nightmare on Elm Street”

The transcending nature of “A Nightmare on Elm Street” is not in how it establishes a unique premise or even an important villain, but in how its actors buy into the material with such vivid implications. When Wes Craven first made his daring and graphic foray into the nightmarish visions of weary teenagers, how was he to know that it would provide more than just a momentary thrill for audiences of that generation? What were the odds that it would be cited so many decades later as a critical benchmark in the evolution of mainstream horror films? Could he have predicted that Freddie Krueger, such a vicious and unrelenting S.O.B., would also persist in the memory bank of notable movie villains? It is because his cast of relative unknowns believed in what they were submitting to with such unwavering conviction that the tragedy of their existence throbs on so effectively in our modern awareness, often informing the movies that continue to emerge from its shadows. Absorbing it now, thirty years from the first moment it shattered the dead teenager genre’s proverbial glass ceiling, is like reliving a primitive (but powerful) attempt at understanding a dangerous world of evil. It forces us to inherit these nightmares as if extensions of our own.

Tuesday, September 30, 2014

The Maze Runner / *1/2 (2014)

A mechanical cage transporting a frightened teenager penetrates the surface of a grassy field, and the figure inside is immediately swarmed by curious onlookers. He has arrived in “the Glade” just like all those before him have done: with amnesia and anxiety, lacking awareness of the reality and yet alarmed by the rhythmic familiarity it seems to instigate in others. It is a routine that has followed the residents of this isolated civilization of young boys for well over three years: every 30 days, someone new arrives, and always it is a young man who remembers little beyond his given name (“It’s the only thing they let us keep”). Their witless imprisonment is contrasted by what surrounds their enclosed reality: a giant maze with walls as high as the sky, which looms as if beckoning would-be adventurers while inspiring a fear of great depths. Each day, a gate opens and offers them entry; every night it closes, and those caught inside are devoured by creatures referred to as the “Grievers.” It is a pattern that that has followed them for as long as they remember, and they no longer question or resist it. But things will change for them with the arrival of this particular individual. They have to, otherwise there wouldn't have been reason to make him the focus of an entire movie.

Sunday, September 28, 2014

Star Trek / *** (2009)

The ongoing saga of the Starship Enterprise has never been in synch with my science fiction tastes. For well over six decades, Gene Roddenberry’s “Star Trek” imprint has persisted in the mind as the watershed serial of televised space operas, amassing a following of adventurers that makes even the most faithful of fan bases – including that of “Star Wars” – look like miniscule social gatherings. But what was it about a bunch of middle-aged men with monotone distinctions and bland uniforms sitting passively at the control panel of a spacecraft that stimulated television audiences in the 60s? Were they so absorbed by the uniqueness of the situation that they mistook novelty for depth? Something that has escaped my notice clicked with the collective psyche of a generation of new thinkers, but their devotion nonetheless paved the way for the plethora of endeavors that have followed this universe, ranging from several series spin-offs to toy lines and, inevitably, to movie adaptations. Seeing these kinds of characters on the big screen, alas, is a lot like watching a foreign film without subtitles: sure, there’s clearly something going on in through a succession of images, but I’d be damned if I knew exactly what (or worse yet, cared).

Saturday, September 20, 2014

Dirty Dancing / * (1987)

“That was the summer of 1963,” a voice chimes in during the opening moments of “Dirty Dancing.” It belongs to one Frances Houseman (Jennifer Grey), the youngest of a posh east coast family, who is nicknamed “Baby” by everyone around her from the moment she wanders into an upscale resort for summer vacation. What brings her (and her relatives) to this getaway spot involves little more than privileged indulgence, but for her, the occurrence eventually seems to take on a deeper meaning. In the days before the world knew who the Beatles were, Baby’s thoughts are all about two things: joining the Peace Corps to study economics in third world countries, and wondering if she’ll ever “find a guy as great as my dad.” The first sign that we are dealing with a girl of questionable insight lies in that particular observation; because her father, played by Jerry Orbach, doesn’t have a very engaging demeanor outside of always looking morosely detached, one wonders what any kind of daughter could find so attractive about such a personality. But hey, cut a girl some slack: her frame of reference may be handicapped far too early for any screenplay to do much with it.

Saturday, September 13, 2014

Blood Glacier / *1/2 (2013)

Had “Blood Glacier” been made from within the big studio system, audiences would likely be hailing it as the worst film ever made; but in the hands of an amateur B-movie director who operates from a place of calculated silliness, it at least inspires uproarious howls of delight – especially if you are a viewer that has any kind of background in science. In some twisted way, it all comes down to intention. So many rules about human and animal biology are broken in this zany creature feature that it calls into question the sanity of the writer, Benjamin Hessler. Was he under the influence of illegal substances when he concocted this absurd premise? His audacity becomes our pained amusement, and for 98 jaw-dropping minutes we watch on – sometimes with horror, other times with laughable shock – as a story about hybrid mutants slithers around on screen as if in the final throws of dramatic suffering. This is one of those endeavors that will no doubt endure the test of time on viewing lists of very ambitious bad movies.

Thursday, September 11, 2014

The Hunger Games / ** (2012)

Of all the young new heroes that populate modern literature, I can’t imagine many readers wanting to step into the shoes of Katniss Everdeen. To imagine how long it must have taken her to develop such a resigned outward demeanor in a universe as bleak as “The Hunger Games” is discouraging; stoic and deadpan in her own circumscribed existence, she creates an identity of unspeakable wounds, and becomes the hopeful face of a generation of oppressed prisoners not out of coincidence, but from an act of sacrifice that is taken (at least in the poverty class) as a reawakening of human will. To live in a world as wildly fascist as that of hers is to see the unrestrained influence of a far-reaching dictatorship, and when Suzanne Collins wrote the novel that this movie is based on, it was clear that her influences included, among other things, the German occupation of Europe during the second World War (where the concept of ghettos and concentration camps essentially found definition). Her points may very well be sound education for their intended audiences; to see them visualized in a very ambitious movie, and in the skin of a youthful fantasy entertainment, it wobbles on a divisive tightrope that left me with an alarming sense of unease.

Monday, September 8, 2014

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles / * (2014)

Something about a reptile in a ninja mask makes my heart sink. “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles” marks the fifth attempt at bringing four wisecracking, mutated kung-fu enthusiasts to the big screen, and the outcome goes beyond all preceding endeavors and plays like the disintegration of an entire industry standard. What inspires filmmakers, usually ambitious ones, to find amusement in this kind of material? How do they justify an idea so clearly intended for Saturday morning cartoons being worth a consistent greenlight at the movie studio? The notion that their decisions are driven by ambitious production values and over-inflated budgets certainly adds clarity to the argument; from the very first over-produced frame, it is clear that not a single moment was spent developing characters with personalities here, much less a story that could offer some sort of challenge beyond keeping names straight. Whatever the final point was, I dunno, but eventually it becomes lost in a laundry pile of inane action and dialogue that often inspires groans of depression rather than enthusiastic joy. Any endorsement of this film would be like admitting defeat against the declining standard of summer entertainment that I have been so vocal against.

Friday, September 5, 2014

Joan Rivers, 1933 - 2014

“If you laugh at it, you can deal with it.”

What a troubling month this has been for the world of comedy. In a short span of a few days that also saw the untimely death of Robin Williams, the loss of Joan Rivers inspires contrasting reflections. In one respect, both of these gargantuan comedic figures were distinctly different – one was a showman with an unending zest for cheerfulness, and the other was honest and sometimes intensely scathing. Both also went through immense inner turmoil that quietly drove them to use stand-up as a treatment regimen, especially in their later years; for Robin, unfortunately, such factors could not cure him of emotional unrest. What takes Joan away at the ripe age of 81 is unfortunate considering how active she was right until the end of her lengthy career, but her death brings with it the acknowledgment of the great (and sometimes unending) power of laughter: that in many cases, it creates an opportunity for us to neutralize the things that so frequently destroy our peace of mind. That she remained a steadfast champion of that belief until her last waking moment goes to emphasize her status as the most disciplined comedian of our time.

What a troubling month this has been for the world of comedy. In a short span of a few days that also saw the untimely death of Robin Williams, the loss of Joan Rivers inspires contrasting reflections. In one respect, both of these gargantuan comedic figures were distinctly different – one was a showman with an unending zest for cheerfulness, and the other was honest and sometimes intensely scathing. Both also went through immense inner turmoil that quietly drove them to use stand-up as a treatment regimen, especially in their later years; for Robin, unfortunately, such factors could not cure him of emotional unrest. What takes Joan away at the ripe age of 81 is unfortunate considering how active she was right until the end of her lengthy career, but her death brings with it the acknowledgment of the great (and sometimes unending) power of laughter: that in many cases, it creates an opportunity for us to neutralize the things that so frequently destroy our peace of mind. That she remained a steadfast champion of that belief until her last waking moment goes to emphasize her status as the most disciplined comedian of our time.

Tuesday, September 2, 2014

Sin City: A Dame to Kill For / *** (2014)

In the weeks leading up to the release of “Sin City: A Dame to Kill For,” Frank Miller’s nourishing cityscape of shadows and corruption weighed heavily in my thoughts. Over nine years had passed since Robert Rodriguez took us through our first outing of Basin City, and yet the visual – and narrative – impulses seemed as fresh in the current moment as they had been all that time ago, when they might have still been seen as distinctive. What gave them that edge was more than just a breathtaking sense of space and dreaminess in the images; they were compelled by an undercurrent, a chutzpah, to use the camera frame as a prison for an ensemble of characters driven beyond the limits of acceptable human behavior. The notion that their seedy antics were executed in a movie with astounding artistic sensibilities was little more than a bonus, and over the years many of us have revisited those damp streets and violent characters in unending awe of the material: marveled by the film’s evocative look and endlessly fascinated by the faces of those who dwell within them. They are, at the core, complex madmen who are only beginning to divulge their dangerous riddles.

Friday, August 29, 2014

Lessons from Criterion:

"Belle de jour" by Luis Buñuel

Few faces in the movies have contemporized storytelling standards as swiftly as Catherine Deneuve’s. When she is brought into the early scenes of Luis Buñuel’s “Belle de jour” – the movie that would ultimately announce her as a force of reckoning in European cinema – her expression is one of vacancy interlaced with ambiguous yearning, as if frozen in a moment of lost inspiration. Before dialogue punctuates those gazes, audiences are immediately drawn to her distinctive features; sharp and porcelain, they clearly do not assent to the same standards of early Hollywood starlets. The eyes are not glossed over by traditional values, either, but seemingly searching for something different, something forbidden. But of what, exactly? Are they paralyzed by the grind of a maddening routine? Are they stirred to discomfort by the unnerving finality of a marriage? Though incessantly voracious, her expressions do not draw obvious attention to the unrest in any of those around her, because that is part of her elaborate game. As the simple but calculatingly elusive Séverine, Deneuve creates a character that fills the space with a sense of wild destiny. She is not a pawn in a screenplay of emotional chess moves, but a firm hand moving around all the pieces in a game she slyly rewrites the rules for. Imagining her now, in a generation of female empowerment, is like witnessing the birth of a standard in the face of an accidental archetype.

Wednesday, August 27, 2014

Richard Attenborough, 1923 - 2014

Towards the end of Shekhar Kapur’s “Elizabeth,” the elderly advisor William Cecil is brought to a sobering concession during a scene he shares with his resolute queen. In that moment, there is no politics or intrigue influencing their dialogue – only gratitude, which briefly releases them from the enslavement of their professions so that they can share an exchange of subdued recognition. Her respect for him is emphasized in a face of growing wisdom, and the kiss he bestows on her hand is an impulse of civility that seems to hold back tears. It is not an act of defeat to be dismissed, but a gesture of goodwill for a man who gave his all for the safety of his monarch. Knowing now that it will forever be one of Richard Attenborough’s final keynote performances in a major motion picture, the scene seems to take on new life as an autobiographical metaphor, as if to suggest that the final bow was his way of saying farewell to a cinema he had bestowed so much resounding influence on for well over fifty years.

Wednesday, August 20, 2014

Wreck-It Ralph / ***1/2 (2012)

So there he is, clambering his way towards the top of a pixelated high-rise, and his gargantuan fists intend to pummel the façade until it all crumbles under the weight of his massive form. A craftsman armed with a magic hammer is the only one in a crowd of panicked figures capable of undoing that damage; if he matches his adversary’s speed and accuracy long enough to neutralize the smashing, then the building will recover, its citizens will persevere, and the destructive brute will be tossed over the side in an act of cheerful celebration. The formula is a simple pattern of competing wits, but that is all the program requires it to be, really. From those little windows inside powerful game boxes standing at the local arcade, missions present clear challenges to those at the controls: find victory in simple worlds of singular problems, and achieve a high score (or advance to later levels) before the quarters run out. What none of the players realize, however, is that the characters within these game boxes actually have their own lives and identities, and when the systems are shut down for the night, they engage one another within the walls (and wires) of a virtual society. Not since “Toy Story” has an idea for an animated movie been so audacious to assume that lifeless instruments of amusement can possess real emotions, much less the instinct to aspire for things beyond their intended use.

Monday, August 18, 2014

Deliverance / **** (1972)

“Sometimes you have to lose yourself before you find anything.”

Hindsight is an attribute that can diminish the value of films that once walked the fine line of visceral envelope-pushing, but to possess it also allows for deeper observations. Consider John Boorman’s “Deliverance” as a noteworthy example; released in 1972 well before the full disclosure mentality of filmmakers drove the underlying current of popular cinema, it was once considered the most explicit mainstream drama of its kind. Just as audiences were taken aback by the implication of simple characters stumbling into frightening realities, a good portion of viewers were greatly unnerved by another key suggestion: that the back corners of the American south could also be hotbeds for cruel and disturbing behaviors. These ideas informed an entire way of thinking that would become the running joke of southerners throughout popular culture, ultimately inspiring the likes of “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre” – that is, movies where the underbelly of horror was often localized in wooded areas populated by inbred villains. Four decades have passed since that approach left an imprint, and nowadays the ideas are commonplace and tired, and often without artistic foundation. To see them at the source, in a movie far removed from the desensitized nature of modern violence, is like staring back at a relic. And yet despite such facts Boorman’s film still speaks to us in profound ways, as if to indicate hidden wisdom has long rested in frames glossed up by a once-shocking philosophy.

Hindsight is an attribute that can diminish the value of films that once walked the fine line of visceral envelope-pushing, but to possess it also allows for deeper observations. Consider John Boorman’s “Deliverance” as a noteworthy example; released in 1972 well before the full disclosure mentality of filmmakers drove the underlying current of popular cinema, it was once considered the most explicit mainstream drama of its kind. Just as audiences were taken aback by the implication of simple characters stumbling into frightening realities, a good portion of viewers were greatly unnerved by another key suggestion: that the back corners of the American south could also be hotbeds for cruel and disturbing behaviors. These ideas informed an entire way of thinking that would become the running joke of southerners throughout popular culture, ultimately inspiring the likes of “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre” – that is, movies where the underbelly of horror was often localized in wooded areas populated by inbred villains. Four decades have passed since that approach left an imprint, and nowadays the ideas are commonplace and tired, and often without artistic foundation. To see them at the source, in a movie far removed from the desensitized nature of modern violence, is like staring back at a relic. And yet despite such facts Boorman’s film still speaks to us in profound ways, as if to indicate hidden wisdom has long rested in frames glossed up by a once-shocking philosophy.

Tuesday, August 12, 2014

"Elizabeth" Revisited

“It is a masterful exploration of the rich and fascinating world of Elizabethan England; the story of the Virgin Queen, the court’s rude luxury, and the atmospheric tones of life behind the castle walls scramble off the screen like deep hidden secrets of the past just waiting to be revealed.” – taken from the original Cinemaphile review of “Elizabeth”

In a key moment of dreamy perfection, a scarred monarch stares back at her reflection in the mirror and announces, unequivocally, that she has “become a virgin.” What is she suggesting? To understand the implication, one must comprehend the veracity of her journey up to that one moment. In 16th century England, political unrest has paved the way for violent religious persecution, and a Catholic rule is threatened when its current queen, Mary Tudor, becomes terminally ill before producing an heir. All thoughts of the crown falling to her sister Elizabeth, a Protestant, inspire proclamations of damnation, and her almost childlike naivety serves to create an emotional current that amplifies the exploits of her devout enemies. But scrawled across this face of intense consideration is the soul of a woman bound to unwavering endurance, and as her command over the country is tested by quiet betrayals occurring all around her, she comes to see this moment – this one revelation – as the only means of rising above a difficult world of violence and suffering. That she has to discover the necessity of this impulse out of terrible heartbreak (and murderous plots) is as sobering as it is tragic.

Monday, August 11, 2014

Robin Williams, 1951 - 2014

“When in doubt, go for the dick joke.”

Reminders of our mortality usually arrive in cruel increments. Today, a collective sweep of grief underscores that notion as we are hearing news of Robin Williams, who at age 63 was found dead this morning in his California home of mysterious causes. Specifics regarding his untimely demise are ongoing, but there is one thing that will persevere as a certainty in the wake of this reality: Williams was more than just a good actor and comedian, he was also a man whose endeavors were delivered with such consistent zeal that it garnered him millions of enthusiastic fans. While most applauded his comedic ability – namely, his penchant for embodying characters of endless quirk, and his knack for skillful improv – it is his endeavors in a slew of thoughtful dramas that resonate in this moment, and seem to emerge as the first thing on our minds as we reflect on his remarkable career.

Reminders of our mortality usually arrive in cruel increments. Today, a collective sweep of grief underscores that notion as we are hearing news of Robin Williams, who at age 63 was found dead this morning in his California home of mysterious causes. Specifics regarding his untimely demise are ongoing, but there is one thing that will persevere as a certainty in the wake of this reality: Williams was more than just a good actor and comedian, he was also a man whose endeavors were delivered with such consistent zeal that it garnered him millions of enthusiastic fans. While most applauded his comedic ability – namely, his penchant for embodying characters of endless quirk, and his knack for skillful improv – it is his endeavors in a slew of thoughtful dramas that resonate in this moment, and seem to emerge as the first thing on our minds as we reflect on his remarkable career.

Friday, August 8, 2014

The Story So Far

It was sixteen years ago when the movies emerged at the forefront of my professional aspirations. The first film that sparked that drive was Disney’s “The Black Cauldron,” which had just been released on VHS after years of being buried in the vaults. Following an eager viewing, I sat down – as I had done so periodically early on when writing reviews for the school newspaper – and cranked out a five paragraph analysis in just a few short minutes. The endeavor had been at the request of an old user-owned web site that initially launched as a petition to release said movie, which was now taking articles from an influx of enthusiastic new viewers as a way to celebrate the long-delayed arrival of their obscure treasure. From that moment on, my new venture merged fluidly with the pursuit of an identity in the new frontier of the world wide web, and words poured from the mind like liquid without obstruction.

Sixteen years later, I sit at a desk in contemplation of milestones. What are the odds that the first proof copy of my first volume of articles would show up in the mail on the very anniversary date that my first review went live on the Internet? Who could have guessed that it would reach my hands in the same week that I finished writing my 700th full length film review, which has already broken a long list of traffic records? Fate and coincidence seem to be interchangeable words when projected into windows of perspective, but in these travels there exists an urgency to reflect. Because the world is barreling past us in a sweep of maddening velocity, moments to pause are a rarity. But they must be done, especially if we are to understand anything about ourselves beyond surface intrigue.

Sixteen years later, I sit at a desk in contemplation of milestones. What are the odds that the first proof copy of my first volume of articles would show up in the mail on the very anniversary date that my first review went live on the Internet? Who could have guessed that it would reach my hands in the same week that I finished writing my 700th full length film review, which has already broken a long list of traffic records? Fate and coincidence seem to be interchangeable words when projected into windows of perspective, but in these travels there exists an urgency to reflect. Because the world is barreling past us in a sweep of maddening velocity, moments to pause are a rarity. But they must be done, especially if we are to understand anything about ourselves beyond surface intrigue.

Sunday, August 3, 2014

Guardians of the Galaxy / ***1/2 (2014)

When a crowded genre comes to the point of being saturated by clichés and wall-to-wall adrenaline, sometimes a little silliness can go a long way. “Guardians of the Galaxy,” the newest (and most eccentric) of the Marvel comic book movie adaptations, is a mad act of absurd genius: refreshingly creative, quirky, well-staged, beyond visionary, often hilarious and fueled by imaginations that seem to tap into an obscure corner of the mind in order to create an endless array of wondrous images. It left me with the kinds of sensations normally reserved for deep and meaningful science fiction epics. That this comes as a major surprise only makes the response all the more enthusiastic. Who would dare suspect that a preposterous little story of unattractive renegades could inspire high amusement, especially after we have been overrun by traditional superheroes caught up in an interlocking battle that demands rigorous stamina and far-fetched conflicts? No recent summer movie has taken such bold risks and gotten completely away with them, much less offered an audience a thrilling adventure in the company of thoroughly original characters.

Thursday, July 31, 2014

The Descent / **** (2005)

A critical window of insight is what separates the characters in Neil Marshall’s “The Descent” from the disposable line of victims normally seen in modern horror movies. It occurs in the opening scenes, when three female friends are out rafting enthusiastically through treacherous river waters. They share laughs, shouts of warning, and occasional lighthearted screams. Their antics are spied by a man and his daughter from a nearby hillside, both of whom are there to cheer on Sarah (Shauna Macdonald). She is the wife and mother, a woman with few cares in the world beyond this current moment. When the raft pulls into an embankment and the three friends begin to part, awkward glances are exchanged between the man and Juno (Natalie Mendoza), Sarah’s other friend. The third catches sight of these gazes, but does not convey a response beyond internal fascination. And then in the next scene, Sarah and her family are on the road heading back into town when tragedy strikes: he veers accidentally off into the lane of incoming traffic, and a head-on collision with another car ends with the deaths of husband and daughter. Later, long after their world has collapsed under the weight of horrific new adventures, one of them makes an observation that effectively frames the entire premise of their interactions: “we all lost something in that crash.”

Monday, July 28, 2014

12 Years a Slave / **** (2013)

Steve McQueen’s stark, powerful “12 Years a Slave” leaps far beyond the notion of basic film composition and penetrates to the core of the human condition, at a time when the acts of a people left a stain on our civilization from which there could be no return. To see it – and indeed, to experience it – is to be part of one of the most haunting encounters we will ever have with a movie screen. Based on a prevailing memoir of one man’s perseverance during the years of American slavery, the film is the embodiment of historical resonance, and McQueen doesn’t so much direct a picture as he allows his mind to be a vessel for unflinching candor while a camera bears witness. Here is an endeavor so brutal, so honest and stirring, that it inspires a collective pause akin to what “Schindler’s List” did for the subject of the Holocaust.

Saturday, July 26, 2014

Jersey Boys / *** (2014)

There’s narration in “Jersey Boys” that calls to mind the approach of “DeLovely” and “Beyond the Sea,” in which musical stars of the 50s and 60s possess hindsight in what will transpire in their eventful lives. Why exactly do those years call to mind a desire for writers to turn their characters into all-knowing observers in their own histories? Does relating the events through a modern perspective add something significant to the approach? A context, perhaps? For the four young men at the center of Eastwood’s newest movie, it is characteristic of a trend that suggests those times are now too distant for today’s audiences to relate. Here emerges a chronicle of young ambitious musicians who are just starting to find their place and write their legacy, but they speak directly to the camera as if stand-ins to “The Jersey Shore”; they are blatantly vulgar and contemporary, and driven by short-sighted indulgences. And yet their deliberate foresight also serves as some kind of elaborate warnings sign, a prolonged metaphor that seems to underscore the naivety of all aspiring stars in the age of artistic unrest. How unfortunate that the old adage “if only we knew then what we know now” doesn’t allow them to affect such details, even as they watch on fully knowing what fate has in store for them.

Thursday, July 24, 2014

Alien 3 / *** (1992)

“In an insane world, a sane man must appear insane.”

The opening images reverberate with distinct tension. A leathery egg appears in the corner of a chamber, recently opened. The window of a cryotube cracks as something unseen scurries nearby. A generic computer voice overhead warns of an internal fire. Then there is a shot of a facial x-ray, with an alien specimen latched on. Acid blood spills on the floor, eating away at it. For those well versed in the stories of the “Alien” pictures, these moments foreshadow a familiar reality: the slimy creatures have left behind a terrible present on this escape pod, and the three survivors of James Cameron’s brilliantly effective “Aliens” are immediately thrust back into danger, all while their vessel passes silently among the stars. That they face this danger while still in hyper sleep is one of the many challenging moments of this, the third picture in the franchise, but their intentions remain in doubt for many seasoned observers: was this collection of shots an attempt by a then-inexperienced director at taking a story arc to the brink of its potential, or were they merely moments of blinding miscalculation meant to abandon the momentum set up in the previous entry?

The opening images reverberate with distinct tension. A leathery egg appears in the corner of a chamber, recently opened. The window of a cryotube cracks as something unseen scurries nearby. A generic computer voice overhead warns of an internal fire. Then there is a shot of a facial x-ray, with an alien specimen latched on. Acid blood spills on the floor, eating away at it. For those well versed in the stories of the “Alien” pictures, these moments foreshadow a familiar reality: the slimy creatures have left behind a terrible present on this escape pod, and the three survivors of James Cameron’s brilliantly effective “Aliens” are immediately thrust back into danger, all while their vessel passes silently among the stars. That they face this danger while still in hyper sleep is one of the many challenging moments of this, the third picture in the franchise, but their intentions remain in doubt for many seasoned observers: was this collection of shots an attempt by a then-inexperienced director at taking a story arc to the brink of its potential, or were they merely moments of blinding miscalculation meant to abandon the momentum set up in the previous entry?

Thursday, July 17, 2014

Hitler's Children (2011)

Five names, five lives forever cast in the shadows of evil. Their faces are hard-worn from existences that seem almost otherworldly, their expressions indicative of countless years of brooding and self-loathing. Who are they? What significance do they hold? Has their experience lead them to outright detachment? They are some of the last descendants of the Nazi empire, and coursing through their veins is the blood of a legacy that will forever haunt them, torture them, and subject them to certain social exile. That they have spent their entire lives atoning for the sins of their ancestors is critical in the study of their troubled lives, but why should they have to go through all of that now, so long after the dust has settled? Are the horrors of our parents and grandparents so potentially horrific that they could, quite possibly, reverberate into the histories of those who come long after?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)