There is material in “Django Unchained” that is unconventional even by the standards of the notorious Quentin Tarantino, whose movies over the past twenty years have been celebratory excursions through all things eccentric and inspired. Some new energy, or desire, must have possessed him here. After gleefully rewriting history for the purpose of an audacious payoff in “Inglorious Basterds,” no longer does the cinema’s most blunt self-made director seem content on just unscrewing the wheels on the car in the last lap of a narrative racetrack. Now, the cars veer off the track itself long before the first sequence even plays out, and characters are beckoned into the shadows of ambition that provide no promise of anything other than long stretches of stylish violence and dismay. The obligatory touches of quirk coupled with repeated nods to the vengeful nature of spaghetti westerns still exist, but here is the movie in the director’s ever-evolving catalogue that finally arrives at the center of an exhaustive trek through the corners of lurid cinema, marking a critical tipping point in a creative march that suggests, yes, Tarantino’s education is at last complete.

Tuesday, July 30, 2013

Monday, July 29, 2013

Lessons from Criterion:

"The Phantom Carriage" by Victor Sjöström

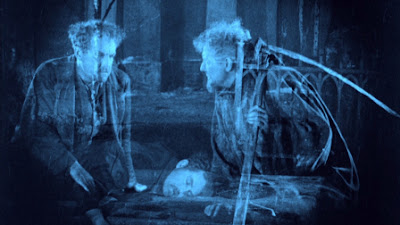

In tracing the origins of Ingmar Bergman’s screen identity back to the Swedish silent fable “The Phantom Carriage” – a movie he claimed was instrumental in his desire to become a director – one also unearths other important revelations within the frames of this puzzling endeavor. Produced and filmed in 1921 at the height of Swedish cinema’s love affair with fantasy and folklore, the movie seemed to write a language from which a future of important filmmakers would be passively influenced. Consider a sequence in which in which the conflicted anti-hero, David Holm (Sjöström), hacks down a locked door in a vain attempt to prevent his wife and children from deserting him – this harkens us immediately back to a key moment in Stanley Kubrick’s “The Shining,” when Jack Torrance does the same in a flash of psychological splintering. Other measures are equally striking: the overreaching presence of death as a puppet master directly inspired the core theme in “The Seventh Seal”; the conflicted main character’s reckless and destructive pattern would be later echoed by the likes of “Scarface” and “Taxi Driver”; and the use of redemption in the climax, especially in the face of certain mortality, would become the defining tone evoked in “It’s a Wonderful Life.”

Thursday, July 25, 2013

...And so begins the third act

Two months into reviewing movies again following a discernible absence, I am possessed by a drive that bewilders even me. Output seems to come from an unknown source imbedded in some deep dark spot of my cranium, funneling material to my fingers that previously only seemed to come in brief stretches of inspiration. Maybe the state of mind I occupy in 2013 is indicative of this new desire, but I’m not entirely sure. What I am sure of, however, is that I don’t care so much about trying to be perfect anymore, or burdened by a worry of releasing something of mediocre standard. No one who cares about their craft improves by simply exercising a creative muscle in infrequent passages. Perfection just does not exist. I have written nearly 30 movie-related articles and essays in just the span of six weeks, far exceeding my level of prolific output of the past eight years combined, and of all the lessons to be learned from this new venture, the most important is that the activity has armed me with a level of self-confidence that was noticeably absent in the recent years. Moreover, what is the point of stressing over the idea of each endeavor being precise if in the end you are improving yourself overall with each conscious attempt?

Wednesday, July 24, 2013

Ratatouille / ***1/2 (2007)

It was no small feat to feign enthusiasm at the prospect of Walt Disney Pictures acquiring ownership of Pixar Animation, especially on the eve of the release of “Ratatouille.” After a string of successes on part of the CGI-geared cartoonists – all of whom had nearly full creative ownership of all their stories and images prior to Disney’s distributing of them – the idea that the future material of this immensely successful studio would be under direct guidance of the gargantuan Mouse House corporation felt, well, like an uncertain reality. For the company whose founder gave birth to the medium of feature animation, this prospect is dismaying, and underscores a surprisingly underwhelming trend of in-house animated endeavors in the recent years, which seems fueled less by creative desires and more by mass marketing potential (save for “Treasure Planet,” which was full of wondrous ideas but failed commercially because of its narrow appeal). The question then becomes, how can the consistency on part of the Pixar name possibly keep up, especially in the hands of a system now long absolved to settling for the median in this genre?

Monday, July 22, 2013

Lessons from Criterion:

"The Seventh Seal" by Ingmar Bergman

A sobering awareness rushes across the face of Antonius Block as the waves of the ocean crash on his beach like relentless reminders of a bleak reality. His eyes glance suspiciously to a vision beyond his comprehension: a man in a hood who observes the spot at which he rests, his face grimly sinking into the visage of a skull, and his dark robes all too eager to invite one into an unknown fate. There is no moment of reaction, only short exchanges. “Who are you?” he asks. “I am Death,” the figure responds. “Have you come for me?” “I have long been at your side.” The dance of banter leads to an indomitable wager: Antonius and Death will engage each other in a game of chess, one in which the outcome will offer the determined knight reprieve from his stalker’s grim clutches, or to mortal conclusion. But in all things for this simple being of a thousand internal struggles, is the final destination really relevant if any of the answers he has agonizingly pursued throughout the painful trek of his life do not come?

Friday, July 19, 2013

Evil Dead / * (2013)

Deep in the woods underneath a rickety old cabin lies a weapon of great chaos and suffering. A potent stench of death acts as a wall against would-be adventurers, and corpses of cats line the basement ceiling as darker warnings to those willing to abandon all reason. At the end of the room, a bulky book seemingly made of flesh is wrapped in plastic and barbed wire, and its presence is of such chilling proportions that it inspires the soundtrack to reverberate lowly across the theater speakers. Inside, anxious scribbles serve as a last-ditch plea: “Leave this book alone.” But anyone who has ever made a horror movie, or more importantly seen one, knows how fool-hearted such declarations are when in the face of naïve 20-somethings who all wander away from civilization. Words are spoken out loud by one such moron, and a great presence of evil is awakened in the woods whose mission becomes clear right from the start: possess the five one by one in succession, corrupt their souls and mutilate their bodies, and open a gateway that will allow hell to overtake the world and consume it in eternal damnation.

Thursday, July 18, 2013

Oz the Great and Powerful / ** (2013)

It’s hard to comprehend how this could have gone so wrong. The wondrous childhood realm of Oz, of witches and munchkins and flying monkeys and little people made of china, is a ripened fantasy world that has dangled luscious fruit in front of our eager faces for well over a century, and yet has endured a stigma of untouchable notoriety for well over half of that time. No doubt the immense success of MGM’s “The Wizard of Oz” in 1939 shut all sorts of future windows for ambitious filmmakers who desired a taste of the literary pie, but time would inevitable allow those windows to be shattered (the first attempt in 1985, “Return to Oz,” added an adult subtext but failed at exploiting the deep-seeded magic of the stories). Now comes “Oz the Great and Powerful,” a movie about the untold adventures of the mischievous and manipulative man who would become the great Wizard, and the prospect of revisiting the elusive magical country is astonishing. Coupled with the notion of a talented and successful director like Sam Raimi being at the helm, all the key ingredients for a highly anticipated prequel line up effortlessly, and the idea seems ironclad. And yet somehow we wind up with a great looking mess, a movie that encompasses technical brilliance and breathtaking images but never lets them off the autopilot setting.

Wednesday, July 17, 2013

P.S. - I Love You / 1/2* (2007)

Tuesday, July 16, 2013

Despicable Me 2 / ** (2013)

I suppose it all comes down to the minions, really. Spastic one-eyed creatures that can be aptly described as Twinkies with teeth and legs, these mischievous beings of unknown origin are at the core of the comedic spine in the “Despicable Me” films, notable for their roles in an assortment of randomized sight gags that have little to do with the story but are potent in generating loud chuckles and enthusiastic grins. So effective is their presence, in fact, that I would wager a movie entirely about their antics would be welcomed immediately by moviegoers, even though their purpose as distractions in a story written with other sights in mind is tangible. They are simply too amusing to ignore, and a highlight, even for us adults, in a series with more traditional aspirations. This perhaps says more about the quality of said movies rather than the creatures themselves, but I digress.

Monday, July 15, 2013

Lessons from Criterion:

"The Night Porter" by Liliana Cavani

Friday, July 12, 2013

The NeverEnding Story / ***1/2 (1984)

As a general rule of thumb, the movie buff is wise to plead ignorance on most things associated with 80s movie fantasy. Widely seen as the decade of origin for this cinematic subgenre, the results were often coarse and uneven, limited not just by over experimental (and overzealous) writing but also by technical limitations that often clashed with the entire purpose of fantasy, which is to be taken to places beyond the wildest in imagination. Some attempts were of ample satisfaction (“Willow” and “Ladyhawke”), others just plain mediocre (“Labyrinth”) or, worse, ridiculous (“Legend”). John Boorman’s “Excalibur” was the only of its kind to break free of those chains and remains the defining spectacle of that time, but, perhaps, not widely accepted as such since its source material is rooted less in pure fantasy and more in literary legend.

Thursday, July 11, 2013

Lo / **1/2 (2009)

Sometimes it makes more sense to let go than to pursue that which is out of reach. Justin (Ward Roberts) could have used such a lesson long before the opening of “Lo,” when his quirky relationship with an enigmatic girl named April (Sarah Lassez) reached a fever pitch before ending under very unfathomable circumstances. What halted their ill-fated nuptials is only one of many minor points of backstory in a flashback-minded movie, but this much is key: the mysterious book she left behind becomes an important link to her current whereabouts, and it allows a door to open that only the most dedicated ex-boyfriend would dare step through. That, or the most naïve.

Wednesday, July 10, 2013

Cloud Atlas / **** (2012)

It is, indeed, the human spirit that causes ripples across eras. Covertly hidden under vessels of flesh that grow and wither far too sudden to keep up with the long meditative vibrations of the universe, our life essence endures across countless unmeasured passages of time, absorbing experiences as they go, and unconsciously echoing them in unbroken cycles. Other souls will collect these lessons as they too pass across the wheel that binds us all, carried with an unspoken desire, or hope, of defusing the tragedies that reverberate. An underlying free will fuels this need, but is the flesh strong enough to realize such purpose? Or is it cursed to the fate of only momentary thought, refuting history and reason for the sake of instant outcomes? There is a profound force of connection ebbing in our collective cognizance, and only some ever look deep enough to feel it weaving through them.

Tuesday, July 9, 2013

Now You See Me / *** (2013)

Stage magic is the plot device of a thousand outcomes. The utter chutzpah of showmen whose elaborate tricks become the crux of a movie screenplay routinely come with the same predicament as magic shows themselves, which is that the overreaching effect can easily be offset by implausibility if the material on display lacks focus, or fails to exploit any possible sense of wonderment. The “magic” on display, too, must inspire us to think about their mechanics and execution; because tricks are designed as momentary thrills, they only resonate if the audience is bathed in their intrigue. When the ingredients come together successfully, you get films like “The Prestige” or “The Illusionist” – endeavors that work well from the narrative context while at the same being thought-provoking entertainment. On the flip side of the coin, you can get something as ludicrous as “The Incredible Burt Wonderstone,” which cares nothing about the craft and uses it as a cheap tool to propel much less interesting ideas and laughs.

Monday, July 8, 2013

The Quandary with Star Ratings

Due to a recent reappearance of movie-related articles and ramblings at Cinemaphile.org, an acquaintance posed a question that is cause for something reflective: “Dave, isn’t it time to retired that four star rating system and advance to the five-star scale that everyone else is using?” My initial knee-jerk response was “no,” because the scale I use has been my system for 16 years, and as the old adage suggests, “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

But then the thought festered somewhat, exposing certain insecurities into a standard that really wasn’t so secure in the first place. Why, indeed, did I use the four-star scale as opposed to the five? Certainly, a more compact rating system was more restrictive, especially for the kinds of movies that perform elaborate balancing acts in various grey areas that make it difficult to pinpoint them on such a narrow measure of quality. Five stars offer a freedom that is less crowded, allowing us to distinguish endeavors from one another on a hierarchy that allows for broader considerations.

But then the thought festered somewhat, exposing certain insecurities into a standard that really wasn’t so secure in the first place. Why, indeed, did I use the four-star scale as opposed to the five? Certainly, a more compact rating system was more restrictive, especially for the kinds of movies that perform elaborate balancing acts in various grey areas that make it difficult to pinpoint them on such a narrow measure of quality. Five stars offer a freedom that is less crowded, allowing us to distinguish endeavors from one another on a hierarchy that allows for broader considerations.

Friday, July 5, 2013

Drag Me to Hell / *1/2 (2009)

The title “Drag Me to Hell” offers both literal and ironic inklings to those associated with the movie’s payoff, including the audience. A young woman aspiring for big professional opportunities at a bank makes a grievous error with a mysterious woman who arrives at her desk pleading for help, resulting in a horrific curse that anchors the crosshairs of torment onto her soul for a resulting 100 minutes of loud and foreboding celluloid. Her house thumps with the thundering sounds of something monstrous, and then a shadowy form tosses her around like a torn rag doll. She is attacked in her office garage. Animals hiss and growl as she walks by. She is assailed by visions of a malevolent being who makes clear his purpose of pulling her into an afterlife of endless torture and suffering. And then the movie demands the panic-stricken victim to sacrifice a kitten in a vain attempt to ward off the evil presence… and in that moment, a deplorable line is crossed.

Thursday, July 4, 2013

The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader / ***1/2 (2010)

The difficult road ahead of the Narnia series in the book-to-screen transition is teeming with eobstacles that would call for the demise of countless less ambitious endeavors. To varying degrees, in fact, such fates have already befallen would-be film franchises like the Inheritance series (“Eragon”) and the His Dark Materials Trilogy (“The Golden Compass”), both of which nosedived into oblivion after just one cinematic outing. The dilemma faced by new attempts at capturing the serialized luster of the “Harry Potter” or “Lord of the Rings” films falls primarily on a universal Hollywood standard: are the films capable of making money? And if so, how consistent can that be? In the cases of those earlier examples, a first attempt was enough to warrant a thumbs down from studio heads. In the example of a series like this, however, the future dodders back and forth between a menagerie of factors, not the least of which is the constant nagging question as to whether the financial payout can cross the threshold that would warrant continued offerings.

The difficult road ahead of the Narnia series in the book-to-screen transition is teeming with eobstacles that would call for the demise of countless less ambitious endeavors. To varying degrees, in fact, such fates have already befallen would-be film franchises like the Inheritance series (“Eragon”) and the His Dark Materials Trilogy (“The Golden Compass”), both of which nosedived into oblivion after just one cinematic outing. The dilemma faced by new attempts at capturing the serialized luster of the “Harry Potter” or “Lord of the Rings” films falls primarily on a universal Hollywood standard: are the films capable of making money? And if so, how consistent can that be? In the cases of those earlier examples, a first attempt was enough to warrant a thumbs down from studio heads. In the example of a series like this, however, the future dodders back and forth between a menagerie of factors, not the least of which is the constant nagging question as to whether the financial payout can cross the threshold that would warrant continued offerings.Wednesday, July 3, 2013

Event Horizon / * (1997)

I can’t imagine what intentions the filmmakers behind “Event Horizon” had in making this endeavor, but I suspect their minds exist in a parallel universe where structural rules and logic are cheerfully abandoned concepts. Here they are possessed not by desire or purpose to say something astounding or even entertaining in accordance with their genre of choice, but by a bewildering notion to throw as many scenes of shock and awe at us as possible without the benefit of setup. Most of the scenes are gratuitous in nature, and seem plucked from superior visual sources before being mutated beyond recognition. If I were a psychologist hired to analyze the people who made this, I would conclude that everyone involved needed to take their inner child out back and shoot it.

Tuesday, July 2, 2013

Prometheus / **** (2012)

There is an air of ambiguity circling the story of Ridley Scott’s “Prometheus” that by most standards would lose the patience of hardcore science fiction viewers. Consistent with questions but scarce on answers, clouds of uncertainty whirl to and fro as if traps to intensify potential intrigue, forcing us to view most of the movie through eyes of suspicion even when things appear crystal clear. When characters engage in a trade of information about what they discover, is it truly all that they have discovered? Do the glances they exchange carry hidden purpose, or divulge some deeper meaning into the complexity of their situation? And just when you think a key player in the game has revealed his or her hand, is someone standing behind the shadows waiting to reveal something greater than aforementioned? Here lies a story that revels in the enigmatic almost as much as it thrives on a fostered sense of tension, and the outcome has the potential to be derailing to those whose minds are not willing to dedicate added concentration.

Monday, July 1, 2013

Doomsday / *1/2 (2008)

Neil Marshall’s “Doomsday” is a Whitman’s sampler of bizarre story ideas and visual gimmicks, congealing around a premise that is so straightforward that it affords them no groundwork for stability or realization. And that’s a sad reality, because the director’s prior professional outing, “The Descent,” snuck up on unsuspecting moviegoers and emerged as one of the most effective horror movies of the past ten years. In that film, characters that are oblivious to terror go cave exploring and are forced to endure survival at the hands of natural dangers while potential supernatural forces reveal themselves. Here, the perspective of the screenplay is not so different… except you get the sense that everyone involved never bothered reading through an initial script treatment, and instead placed their faith on a man who has shown he is capable of genuine entertainment at the movie theater, but apparently lacks the judgment skill to be consistent in that conviction.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)