Most film critics are absorbed in best-of lists and awards screeners in the final weeks of any ordinary year. I spent that time in a different frame of mind: one of reflection and meditation, not just over the movies that I saw, but also over the inspiration that encouraged me to return to the keyboard after a lengthy absence in the review world. Between the years of 1998 and 2004 I was under the spell of some sort internal discipline that kept my output consistent; in the years that followed, other life objectives took over, and my commitment to writing was seen only in brief intervals. 2013 marks a comeback that is the stuff of personal miracles, and as I look back I can barely fathom where this new energy came from, or how it managed to stay so consistent after eight years of false starts and wavering objectives.

Tuesday, December 31, 2013

Monday, December 30, 2013

A Christmas Story / **** (1983)

Significant contrasts exist between most movies about the holidays and Bob Clark’s “A Christmas Story,” but the key to its endurance over the years probably comes down to a certain cheerful self-awareness. Here is a movie where characters are not so much born from a script as they are molded within a tangible frame of reference, and through their sense of innocence, patience, imagination and ability to pass through situations with scarcely a shred of confidence, an image of the most bolstering movie family emerges. This, we quickly realize, creates a commodity of alarming clarity: for anyone who has ever experienced the childhood wonder associated with the festive traditions of Christmas (or the agonies of familial impatience), many of the scenes scattered throughout the picture seem to exist as projections, as if the movie camera is reaching into the scrapbook of the mind and drawing on specific memories for reference. Directors by nature look to their own lives for such inspiration, but this is an approach that is impeccably informed and organic, and Clark not only comprehends the emotions associated with suburban households in the hustle and bustle of the holidays, but somehow finds a universal elation in them.

Tuesday, December 17, 2013

Adieu, Mr. Swann

The regal, contemplative Peter O’Toole played a great many characters in his ambitious screen career, but none nearly as arresting as an eccentric British army officer in David Lean’s “Lawrence of Arabia,” which became the primary launching point of his illustrious life in the movies. Classically trained in the ways of theater well before he caught the attention of Hollywood, the part of the flamboyant T.E. Lawrence came to him purely by coincidence; in the weeks leading into production, the offer had gone to Albert Finney, who turned it down because it involved a lengthy contractual commitment. Flustered, Lean saw a quality in the unknown O’Toole that fit painstakingly into the characterization: an ability to deliver lines and gestures with all the nobility of the British etiquette, yet offbeat enough to suggest fascinating undertones beyond what was seen in the frame. The performance is widely accepted as one of the finest captured in that era of “cinemascope” studio epics, inspiring the first of several Oscar nominations and other accolades that would follow him for well over 40 years.

Monday, December 16, 2013

Ender's Game / ***1/2 (2013)

In the colorful but convoluted landscape of movie adventures in which youthful heroes face ominous predicaments, “Ender’s Game” scampers off the screen with something quite distinctive: an approach that demands well-drawn characters to carry the narrative as opposed to audacious visuals or action scenes. All indications of the premise certainly point towards something of formula; in a futuristic era where insect-like aliens invade Earth, are pushed back with military force and then hunted in an elaborate government plan designed to prevent all future retaliation, viewers are ingrained with the prospect of overzealous explosions dominating two hours of screen time. What a remarkable prospect to find the ideas rooted entirely in the faces of ordinary kids, many of whom carry the burden of fate on their shoulders but learn quickly and intuitively that their actions require the strategy of the mind as opposed to the impulse of the heart, otherwise uncertain outcomes risk the future of their very civilization.

Wednesday, December 11, 2013

Grizzly Man (2005)

The greatest mystery of man often lies in the choices he makes, and Timothy Treadwell created perhaps some of the most ambitious riddles one could imagine. For thirteen consecutive summers, the shy and offbeat nomad left the human world behind and went to live in the company of the wildest of animals: large and dangerous grizzly bears in the Alaskan peninsula, many of which had spent their existence so far outside of human contact that he seemed to occupy space in their unrestrained existence as a lone alien. Social awkwardness made him an outcast, while the seeming peace and tranquility of the wilderness inspired buried passions. But what was the purpose of his consistent desire to distance himself from human interaction? What did he see in the grizzlies that gave him purpose? What do hours upon hours of video documentation show us, other than the dogged dreams of one who fell victim to a false idealism about ferocious predators that exist only to feed and survive?

Wednesday, December 4, 2013

Thor: The Dark World / *** (2013)

Movies continue to provide colossal snapshots into worlds that stretch beyond the frame of imagination, and the realm of Asgard in the “Thor” movies is certainly one of the most inspired of recent times. Amidst vast open spaces that seem stirred by Greek mythology rise pillars and towers that jut from a planetary surface like protests to nature, and characters seem to wander through their polished spaces as if insects inside a boundless hive of overreaching hallways and arenas. No wonder, perhaps, that its citizens are immortal beings; for this kind of utopian empire to exist, those that created it must obviously command a power far greater than what man can wield, much less understand. Observing “Thor: The Dark World” in which gods and demons adopt the primary roles of heroes and villains, I was struck not just by how fully realized the realm is, but also by the underlying notion that we as moviegoers have now seemingly exhausted what is palpable in our heads as creative environments to wander through in the movies. It is a fascinating paradox to find yourself in when the imaginative cityscapes of “Blade Runner” and “Dark City” now seem like half-forgotten relics in the celluloid scrapbook. Now what remains beyond the high pearly gates of the world of gods?

Monday, December 2, 2013

Steel Magnolias / ***1/2 (1989)

The six women at the center of “Steel Magnolias” are the embodiment of a social class that went extinct in the trenches of current cultural standards. Their audacious impulses carry the undercurrent of flamboyant storytellers, and when they engage in gossip or berate one another with colorful insults and euphemisms, their convictions are solely from a place of virtue. Sometimes their honesty is laced with a bravado that invites outright dismay, and hurt feelings are only momentary to the shock of a cold truth splashed in one’s face. What ties them together goes to the root of all perceptions of human compassion, but they are not dependents whose lives only mean something with one another filling in a void. They have formulated an unending series of friendships because, basically, their depth is enriched by those who share the same capacity for love, and that capacity is a refreshing sentiment in the hands of a world too busy to stop and smell the flowers.

Monday, November 11, 2013

Shortbus / ***1/2 (2006)

The first moments play like an invasion into the bedrooms of strangers. The camera cuts between three distinct romps: in one, a lone male films himself on a handheld digital camera attempting to engage in auto-fellatio, and the frame reveals the full package. In the next, a couple experiments with varying sexual positions as if attempting to outdo the Kama sutra, and the penetration shots are genuine. In the third, a woman dressed in eccentric dominatrix garb verbally abuses a man for money, whips him, clamps his nipples with clothespins and reveals a gaze of dismay when he winds up having an orgasm on her headboard painting. What do these three scenes exemplify, other than a shockingly frank attitude about the sexual bravado of its characters? For “Shortbus,” the answer is not nearly as simple or one-dimensional as the surface would suggest. This isn’t an exploit into pornographic ideals, but a movie with genuine ideas that are completely freed from political correctness in a time when society continues to fear absolute truths about our individual desires.

Thursday, October 31, 2013

Awake in the Stars – In Memory of Sharon

Sharon Blasing was not always the simplest person to comprehend. Obscured inside a myriad of colorful euphemisms was an approach to life that inspired great consideration, and even more bewildering was the vast data bank of knowledge that permeated from her lips every time they spoke. Nomads wander through time and culture with rigorous intent to collect varying fractions of knowledge, but here was a lady that absorbed all of her surroundings (literal and figurative) like fruits of the Earth, and she did everything in her power to pay the wisdom forward. Sometimes it came out aggressively, and could open old wounds. But there was never malice in that conviction: only a desire to lift others, even if it meant making the journey more rigorous in the process.

These thoughts were not always easy to see, especially in the company of a woman whose external thought process possessed distinct flaws. There was stubbornness in her that was downright infuriating, especially when it came to health habits. She had chutzpah in asking favors, and it evolved often into audacity when they became unspoken expectations. I also recall a lot of heated discussions over politics that seemed ripe in misinformation, and it struck a nerve when she dismissed gay marriage as a “non issue” during the very tense 2012 presidential election. Her intention was never to offend or cause awkwardness, but sometimes those are natural in the face of dissonant perspectives about the world.

These thoughts were not always easy to see, especially in the company of a woman whose external thought process possessed distinct flaws. There was stubbornness in her that was downright infuriating, especially when it came to health habits. She had chutzpah in asking favors, and it evolved often into audacity when they became unspoken expectations. I also recall a lot of heated discussions over politics that seemed ripe in misinformation, and it struck a nerve when she dismissed gay marriage as a “non issue” during the very tense 2012 presidential election. Her intention was never to offend or cause awkwardness, but sometimes those are natural in the face of dissonant perspectives about the world.

Monday, October 28, 2013

Bad Grandpa / *** (2013)

Mel Brooks once said that a good comedy requires no fewer than five big laughs. “Bad Grandpa,” the newest MTV film from the creators of “Jackass,” has exactly that many, with several minor chuckles in between. The first comes early on in the picture when the Grandpa character is conducting the eulogy at his wife’s funeral. Their daughter arrives, indicates she is going to prison for violating parole, and angrily insists on leaving her son behind in his care until the father can retrieve him. They banter back in forth with dialogue exchanges that are overheard in the other room via a microphone that remains turned on between them. Guests are shocked and outraged by some of the vulgar proclamations. And then grandpa returns to the room, shaken up, falls back and the open coffin collapses to the floor, which is then nervously played off by the choir breaking into a hymn while the old man dances with the body. In a traditional comedy this kind of audacity would have inspired guilt in those that found it amusing, but here is a movie that, like “Borat” and “Bruno,” uses its shame in a strategic illusion to get reactions out of unsuspecting victims. And the results are often incredibly funny.

Friday, October 25, 2013

Hostel / *** (2005)

Eli Roth’s “Hostel” is an agonizing experience to sit through – disheartening, unpleasant, bursting with torture, detached and harsh, and unrelenting in its passion for the horrific. To call it a challenge in the visual sense does not begin to explain its ability to completely rob you of the comfort of artifice; it so fully indulges in its reality that every cut, every bloodcurdling moment in which pain is inflicted on a number of unsuspecting victims, is felt rather than seen. That may rob the movie of repeat value even in the hands of audiences who willingly embrace this overzealous sub-genre of torture-driven horror, but it does provoke deeper considerations: in the hands of skilled filmmakers who know how to establish reason and perspective, can extreme visual depravity rise above its nature to merely sicken and appall? Like “Saw II” and “High Tension,” here is a movie that elicits a powerful reaction not simply because it goes for the hardcore, but because it has plausible justification for doing so.

Tuesday, October 22, 2013

Apocalypto / **** (2006)

“A great civilization is not conquered from without until it has destroyed itself from within.”

There are a plethora of subtexts in Mel Gibson’s “Apocalypto” that come scurrying off the screen, but the most commanding of them is also the most subtle: the presence of a calm acceptance encasing the barbaric catastrophes of its characters. Movies often paint portraits of primitive cultures with certain detachment as a way of dealing with their tragedies, but here is a movie that skillfully masks its displacement with an air of alarming cognizance, as if to suggest the material is being viewed from human eyes rather than movie cameras. There is never a sense that what we are seeing is merely staged for an effect of shallow entertainment or even mere education, either. Gibson’s famous “Braveheart” and “The Passion of the Christ” embellish on these feelings, but here the concept arrives at the absolute center of its psychology, and doesn’t look back for any relief. Like a survivor of inconsolable suffering, the movie endures its findings even as they grow darker and more gratuitous. And after two long hours of simple people being victimized, humiliated and tortured beyond comprehension, we are left with a hard reality that points, alas, to a universal pattern amongst all civilization: no force between men is greater than violence, and those that endure do so because they reject fear in the face of immense pain.

There are a plethora of subtexts in Mel Gibson’s “Apocalypto” that come scurrying off the screen, but the most commanding of them is also the most subtle: the presence of a calm acceptance encasing the barbaric catastrophes of its characters. Movies often paint portraits of primitive cultures with certain detachment as a way of dealing with their tragedies, but here is a movie that skillfully masks its displacement with an air of alarming cognizance, as if to suggest the material is being viewed from human eyes rather than movie cameras. There is never a sense that what we are seeing is merely staged for an effect of shallow entertainment or even mere education, either. Gibson’s famous “Braveheart” and “The Passion of the Christ” embellish on these feelings, but here the concept arrives at the absolute center of its psychology, and doesn’t look back for any relief. Like a survivor of inconsolable suffering, the movie endures its findings even as they grow darker and more gratuitous. And after two long hours of simple people being victimized, humiliated and tortured beyond comprehension, we are left with a hard reality that points, alas, to a universal pattern amongst all civilization: no force between men is greater than violence, and those that endure do so because they reject fear in the face of immense pain.

Tuesday, October 15, 2013

Aliens / ***1/2 (1986)

Think of the calculated patience of the Ellen Ripley persona. Here is a woman whose level-headed approach armed her with a foresight that would have allowed all those involved in the “Alien” movies to circumvent confrontations with menacing bloodthirsty monsters, had she not been surrounded by those too lazy or corrupt to follow rules. It was she who anticipated dread when those aboard the Nostromo decided to answer an ambiguous alien distress signal on a remote planet. It was she who refused to open the ship’s hatch when it became obvious that one of her comrades had been exposed to a face-hugging parasite. It was she who expressed discontent over others placing themselves in uncertain danger, even though it may have made her seem unsympathetic in the minds of emotional crew members. It was she who dug deep enough to discover that her crew’s resident android had been programmed to bring the alien life form back to Earth regardless of the safety of others. And when the creature gradually began picking crewmembers off in the shadowy corridors, it was she who stayed focused and committed to the cause of survival, despite the fact that the encounter caused the deaths of all those around her (save for a feline named Jones).

Friday, October 11, 2013

Sex and the City 2 / 1/2* (2010)

Here are ladies of distinct social buoyancy that have now completely lost their mojo. “Sex and the City 2” sees the bravado of four likeable demeanors reduced to the patterns of overpaid escorts; they dress in short scraps resembling dresses, drink as easily as they breathe, smile and charm crowds with superficial gestures, laugh like they are faking courtesy, and take pause long enough to engage in one-note relationship woes or sexual promiscuity, sometimes even when in conservative cultures. Once upon a time these antics were delivered with sharpness and wit that gave them a humorous context, but now they emerge from a place of vulgar excess. Why in heaven’s name did no one high up in this production take long enough pause to warn all of its talented actors that they were participating in a spectacular travesty? Like all bad ideas taken to the pinnacle of development, dollar signs likely negated the need to use logic. I certainly hope they are proud of themselves for their dubious achievement.

Thursday, October 10, 2013

Sex and the City / ** (2008)

The governing powers of television comedy would have salvaged many careers and avoided countless embarrassing situations had they established the following doctrine early on: keep sitcoms on the small screen and out of movie theaters, or else suffer the consequences. Evidence supporting this statement fills a list as long as most wedding registries, while notions to the contrary materialize like sightings of the Tooth Fairy. Consider the girls at the center of “Sex and the City,” for example; as the owners of a piece of prime real estate during the weekly cable network lineup for six long years, they earned a notoriety for taking a brazen approach to the taboos of love and sex: discussing them openly, exploring fetishes, dealing with embarrassment and, more importantly, finding their place in a society where they could only guess the intentions of horny men, and either love or hate them for it. Contrary to the suggestion, it was successful not just because it took provocative risks, but because it framed it all with intelligent contemplation.

Wednesday, October 9, 2013

Richard III / ***1/2 (1995)

There are few certainties rushing through the great Shakespeare plays, but a consensus does persist when it comes to considering the notorious Richard III: he is easily the most vindictive and cunning of all the bard’s major villains. Essays have been written over countless centuries as cathartic measures to understand the ruthless driving forces of his persona: the ability for him to anticipate human response in the face of grief, to manipulate grave tragedies to his political advantage, and to even create a convincing façade that masks his obsessive impulses in front of those who would grant him great power. It was the playwright’s first well-received tragedy, and its endurance through a career punctuated by more highs than lows adds substantial weight to its overreaching influence: for most audiences, the shadowy visage of a hunched man ruthlessly playing his way through the ranks of familial hierarchy represents the kind of multi-faceted antagonist one hopes for in all modern storytelling.

Tuesday, October 8, 2013

Gravity / **** (2013)

A simple spark in the corner of an eye is sometimes all it takes to arouse great visionary endeavors at the movies. Alfonso Cuarón’s “Gravity,” which occupies this sentiment, is the sharpest and most effective science fiction thriller of our time: a triumph of detail and nuance that imagines something from a source of simplicity and then wraps it in a cloak of ambition that carries us through phases of wonderment, despair, alarm and sometimes outright horror. And it does so without sacrificing the critical component of the great space thrillers: its ability to create a mood without overzealous action or special effects. For the talented filmmaker who also made the fantastic “Children of Men,” the movie presents us not only with a worthy successor, but an even deeper truth: his consistent and passionate finesse with a movie camera now places him in the company of Kubrick and Spielberg.

Monday, September 30, 2013

Titus / ***1/2 (2000)

“I shall grind your bones to dust, and with your blood and it I shall make a paste, and of the paste a coffin I will rear and make two pastries of your shameful heads. And bid that strumpet, your unhallowed dam, like to the Earth, swallow her own increase! This is the feast I have bid hereto, and this the banquet she shall surfeit on… and now prepare your throats!”

He knows only what his time and civilization have conditioned him for: to slay the enemy, conquer his lands, and sacrifice all others – including loved ones – who might characterize a divisive strike against his fist or mind. That is the fundamental guiding force of old conflicted Titus, the main character at the center of England’s bloodiest stage play, and with that conviction he clutches an instinct that is hard-hitting and unsympathetic; audiences bear witness to the ensuing brutality like lambs carried through varying stages of slaughter. There is no hope for any who challenge his will, and those that may merely stand in his shadows as cautious observers are subject to similar fates. Like a spinning blade, the aged general of a dying empire crashes through lives without regard to the merits of human existence, and when a maniacal plot for revenge against him begins to escalate in the hands of bloodthirsty dissenters, it becomes only another platform for more macabre crimes against the flesh.

He knows only what his time and civilization have conditioned him for: to slay the enemy, conquer his lands, and sacrifice all others – including loved ones – who might characterize a divisive strike against his fist or mind. That is the fundamental guiding force of old conflicted Titus, the main character at the center of England’s bloodiest stage play, and with that conviction he clutches an instinct that is hard-hitting and unsympathetic; audiences bear witness to the ensuing brutality like lambs carried through varying stages of slaughter. There is no hope for any who challenge his will, and those that may merely stand in his shadows as cautious observers are subject to similar fates. Like a spinning blade, the aged general of a dying empire crashes through lives without regard to the merits of human existence, and when a maniacal plot for revenge against him begins to escalate in the hands of bloodthirsty dissenters, it becomes only another platform for more macabre crimes against the flesh.

Friday, September 27, 2013

A Year Older, A Year Wiser

So the old adage goes, perhaps excessively. Today marks the first day of my 32nd year as a living organism in this strange blue world of ours – that round habitat that has become the groundwork of not only billions of years of change and evolution, but of human experiences, conditions, lessons and intelligence. To think of my own existence as part of a scheme too grand to comprehend is like placing yourself in any key moment in “2001: A Space Odyssey.” No one will ever realize what cause or effect will come with their presence, but to know that there is one – and to maintain that perspective – is beyond profound.

Life is a precious commodity. It is taken for granted so easily, so passively. I know this because I have indulged in plenty of my own time-wasting, usually for no other purpose than momentary satisfaction. I used to think of age as an annoying reminder of new aches and pains working their way into one’s life, and that is not entirely untrue. But it is only part of the big picture, which is bound by the element of time that drifts us ever so closer towards the end of our existence as we know it. That becomes a little scarier to confront each year, but it also puts the present into a much broader perspective. Today is about today, and doing everything you can to live, enjoy, savor and cherish the pleasures of Earth and its gifts. I know this better at 32 than I did at 24, and it’s a remarkable feeling to not only realize it, but experience it.

Life is a precious commodity. It is taken for granted so easily, so passively. I know this because I have indulged in plenty of my own time-wasting, usually for no other purpose than momentary satisfaction. I used to think of age as an annoying reminder of new aches and pains working their way into one’s life, and that is not entirely untrue. But it is only part of the big picture, which is bound by the element of time that drifts us ever so closer towards the end of our existence as we know it. That becomes a little scarier to confront each year, but it also puts the present into a much broader perspective. Today is about today, and doing everything you can to live, enjoy, savor and cherish the pleasures of Earth and its gifts. I know this better at 32 than I did at 24, and it’s a remarkable feeling to not only realize it, but experience it.

Thursday, September 26, 2013

Stand by Me / **** (1986)

When you are an adventure-seeker stuck in that odd transition between early youth and adolescence, few movies resonate more than “Stand by Me.” Our suspicions suggest all the right notes are found not so much on the basis of having gifted filmmakers telling this story, but in the implication that its ideas come from within a collective experience that all men recall with some fondness (or alarm) as they grow older. Rob Reiner, Stephen King and Bruce Evans often find this trait meandering through many of their endeavors, and it’s a wonder they even bother referring to some of those stories as works of fiction. Together, they seem destined to write the prototype for what nearly all male youths will endure on their journey towards a more informed state of wisdom, and here it is all told in a setting where a quiet community is altered by fate’s own sleight of hand, and four spirited individuals are challenged by an event that will compel them to grow up much sooner than they should.

Friday, September 20, 2013

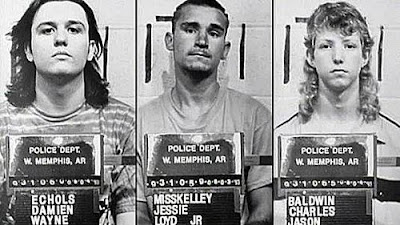

Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory / (2011)

*(star rating not relevant)*

So here is where their nightmare comes to an end. After 18 years of falsified imprisonment, legal battles, unrelenting suspicion and a documentary filmmaker’s camera as their only link to the outside world, the West Memphis Three arrive at the center of “Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory” having learned the harshest lesson about our flawed legal system, and their reward is their own freedom. But at what cost? Two decades of their lives have been lived in isolation for ludicrous reasons, a devastated community spent all their emotional energy on the wrong targets, and the deaths of three eight year olds have gone without justice because an incompetent police force was too careless in their pursuit of facts. And even after the turmoil, none of those involved in the false convictions ever shows the slightest hint of spine; they resolve to their pompous rhetoric that those convicted were done so in a clean case, and the state’s eventual decision to free them based on reduced sentences instead of full exoneration is a spit in the face. Seldom has a film inspired so much dislike in viewers towards the very system designed to protect them.

So here is where their nightmare comes to an end. After 18 years of falsified imprisonment, legal battles, unrelenting suspicion and a documentary filmmaker’s camera as their only link to the outside world, the West Memphis Three arrive at the center of “Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory” having learned the harshest lesson about our flawed legal system, and their reward is their own freedom. But at what cost? Two decades of their lives have been lived in isolation for ludicrous reasons, a devastated community spent all their emotional energy on the wrong targets, and the deaths of three eight year olds have gone without justice because an incompetent police force was too careless in their pursuit of facts. And even after the turmoil, none of those involved in the false convictions ever shows the slightest hint of spine; they resolve to their pompous rhetoric that those convicted were done so in a clean case, and the state’s eventual decision to free them based on reduced sentences instead of full exoneration is a spit in the face. Seldom has a film inspired so much dislike in viewers towards the very system designed to protect them.

Thursday, September 19, 2013

Paradise Lost 2: Revelations / (2000)

*(star rating not relevant)*

The unanswered questions at the end of “Paradise Lost” were the kind that could inspire not only a need for a follow-up documentary, but indeed an entire political movement. In “Paradise Lost 2,” three teenage boys who were tried and convicted in 1994 of a grizzly series of child murders in Arkansas are nearly five years into their prison sentences, and occupy camera frames like mere shells brow-beaten by a due process that failed them. The perplexity of their convictions was instrumental in the creation of a non-profit support organization that is centralized in the second documentary, in which supporters of the “West Memphis Three” take on operative roles in an appeal process that would overturn the conviction of Damien Echols before a proposed death sentence is carried out. Anyone who saw the predecessor with an open mind can easily see why: in a legal climate that was beginning to use DNA and forensics as keys to unlocking the secrets of heinous crimes, how was it even possible that three relatively calm teenagers could be found guilty of murders that they could not be linked to scientifically?

The unanswered questions at the end of “Paradise Lost” were the kind that could inspire not only a need for a follow-up documentary, but indeed an entire political movement. In “Paradise Lost 2,” three teenage boys who were tried and convicted in 1994 of a grizzly series of child murders in Arkansas are nearly five years into their prison sentences, and occupy camera frames like mere shells brow-beaten by a due process that failed them. The perplexity of their convictions was instrumental in the creation of a non-profit support organization that is centralized in the second documentary, in which supporters of the “West Memphis Three” take on operative roles in an appeal process that would overturn the conviction of Damien Echols before a proposed death sentence is carried out. Anyone who saw the predecessor with an open mind can easily see why: in a legal climate that was beginning to use DNA and forensics as keys to unlocking the secrets of heinous crimes, how was it even possible that three relatively calm teenagers could be found guilty of murders that they could not be linked to scientifically?

Tuesday, September 17, 2013

Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills / (1996)

*(Star Rating Not Relevant)*

On a quiet evening in May of 1993, three young boys in a small town in Arkansas were wandering the neighborhoods after school when an assailant abducted, bound and brutally murdered them, and then left their mutilated remains in a ditch in a remote forested area off a nearby interstate. The ensuing events in West Memphis over the following year were of disquieting reality, as details of the crimes were exposed in graphic detail, a community was whipped into a frenzy of fear and anger, and three teenagers were prosecuted for the slayings based on evidence that was perhaps less than circumstantial. That all of this played out in an atmosphere that was rank in overwhelming religious undertones no doubt complicated the matters, but one central question would endure long after the nightmare had ceased: could three relatively docile teenage boys really commit something so heinous, or were they the victims of a hysteria that demanded some kind of finality to a crime too shocking to comprehend?

On a quiet evening in May of 1993, three young boys in a small town in Arkansas were wandering the neighborhoods after school when an assailant abducted, bound and brutally murdered them, and then left their mutilated remains in a ditch in a remote forested area off a nearby interstate. The ensuing events in West Memphis over the following year were of disquieting reality, as details of the crimes were exposed in graphic detail, a community was whipped into a frenzy of fear and anger, and three teenagers were prosecuted for the slayings based on evidence that was perhaps less than circumstantial. That all of this played out in an atmosphere that was rank in overwhelming religious undertones no doubt complicated the matters, but one central question would endure long after the nightmare had ceased: could three relatively docile teenage boys really commit something so heinous, or were they the victims of a hysteria that demanded some kind of finality to a crime too shocking to comprehend?

Friday, September 13, 2013

300 / *** (2007)

The hero at the center of “300” is defined as a man “baptized in the fire of combat,” which might explain the look of almost sadistic pleasure he occupies for two hours. The prologue sets that idea in motion quite literally from the day of his birth, when a mystic holds his writhing infantile figure over a gulley containing the bones of countless discarded children while he conducts an examination for signs of physical flaw (the voice-over informs us that Spartan society tossed newborns into the pit if any were deemed “unsuitable”). Later, as he goes through a structured adolescence of demanding physical tests with dangerous wild animals and public fighting contests, that look of persevering torment seems harmonious with his hardened face – the same look, not coincidentally, that is also permanently etched on the profiles of elders who see the violent upbringing not as seeds for a traumatic adulthood, but rather as the curriculum for those destined to be fierce warriors. It’s a dangerous world out there, especially for a culture that seems content to do battle with swords and shields without breastplates to protect their exposed torsos.

Thursday, September 12, 2013

Riddick / ** (2013)

Wednesday, September 11, 2013

The Second (or Third) Time Around

In my adventures of writing about older movies that I neglected to review during theatrical release periods through the last several years, I realized that I’m not being entirely truthful to my audience. Once upon a time, I wrote that “reviews represented an immediate experience,” and used it as a defense to explain why I could never be one of those critics who would occasionally go back and write a second critique to a film I might have changed my mind on. The flaw in that statement is that the sentiment is negated the moment I choose to write about something that I first saw years prior, yet never got around to evaluating while it was still a commodity at the local multiplex. In order to be informed on a keyboard, after all, the subject must be fresh in your mind; this usually requires new viewings of said movies, and in many cases the opinion is modified because the material has had more time to settle. Opinions indeed are not absolutes, and neither are any claims to the contrary (even when I might be the one making them).

Tuesday, September 10, 2013

Lessons from Criterion:

"Cries and Whispers" by Ingmar Bergman

Three sisters, each separated by different stages of emotional weathering, inhabit a countryside manor like rats quietly feasting on each other’s insecurities. One of them is terminally ill and on the razor’s edge of mortality; the other two have arrived from afar to offer care in her dark and painful final days. One looks askance at emotional displays like a strange and horrifying concept; the other, whose piercing blue eyes overflow with vague desires, shrinks to obscurity in the face of truth. Their lives are framed by the presence of a sole but knowing housekeeper, a frumpy woman whose own loss of a young child has left her broken but nurturing. In an important scene, she comes to the call of the dying woman, opens her shirt and allows her to rest her head on her warm bosom for physical comfort. Their stories intertwine in a narrative soaked in muted desperation, and the deep red interiors of their home act as an organism of imprisonment. What cauterizes their souls and robs them of empathy? And when the darkest of moments come to pass, will they oppose the barriers holding them away from the embrace of familial instinct, or become enveloped in their own shame?

Friday, September 6, 2013

Network / **** (1976)

The famous images of American cinema don’t always endure through generational transitions, but the sequence in “Network” in which Howard Beale explodes with rage on broadcast television will likely be studied for centuries. When it was first revealed in 1976, audiences were caught off guard by the savage proclamation – in an editorial climate that was not yet bankrupt of journalistic integrity, the moment was virtually overpowering in the way it satirized the idea of a regulated national process caving into vulgar sensationalism. Such a moment normally would have faded into obscurity along with countless others weathered by cultural shifts, but in a society that has thoroughly mimicked the movie’s core irony, it finds a distinct resonance. Could the writer, Paddy Chayefsky, have foreseen that his biting sarcasm would become the actual medium’s underlying value system? It is easily the most important and influential image of any movie about this industry: not so much funny as it is precise and visionary.

Thursday, September 5, 2013

Mud / ***1/2 (2013)

The young heroes in “Mud” recall the sentiment of the teenage rebels in Rob Reiner’s “Stand by Me” – they are at that stage of adolescence in which their future will forever be shaped by the experiences of that moment, and the adults around them dictate it with situations of impending emotional gravity. For the four adventurers of Reiner’s film, the turning point was the search for the body of one of their deceased schoolmates; here, the two puberty-stricken boys become caught up in the dealings of an isolated stranger they meet on an island in the Mississippi, which houses a boat that was stranded after being caught between branches high in a tree during the last great flood. Their first encounter is a solemn one: the boys, eager to lay claim to the boat as their property, find fresh muddy boot prints and snacks in the cabin (suggesting it was recently used) and then spy a drifter on the island’s beach fishing. They are curious but distant, for obvious reasons. Nails in his boots leave behind a cross-shaped imprint in the sand. “They just good luck boots,” he tells them. “But you can tell they ain’t workin’ well at all.”

Tuesday, September 3, 2013

Blue Jasmine / ** (2013)

Monday, September 2, 2013

Lessons from Criterion:

"M" by Fritz Lang

Sound was the new frontier in German cinema when Fritz Lang made “M” in 1931, and that insight provides us with the first of many potent ironies: the notable absence of a soundtrack and background noise. Lang, who was more comfortable with the physical theatricality of actors and sets of the 20s, faced that transition with protest, and his shameless desire to rob the first of his post-silent pictures of notable use of the technique was indicative of contempt for the medium’s abrupt expansion. The resulting effect may have been accidental: in a story featuring a predator lurking in the shadows, the only two constants are an occasional cry for help, and a killer’s low but piercing whistle in a metropolis devoid of most obvious sound cues. Audiences might not have contemplated such notions at the time, but in the minds of later generations who were already trained in the full use of theater speakers, the outcome is a startling one, and propels an intrigue in the material that might otherwise have been overlooked in the hands of someone more eager to push the technical envelope.

Thursday, August 29, 2013

The Secret of Kells / **** (2009)

Much gets lost in the winds of change when it comes to feature film animation, not the least being obscure movies that circulate outside of major studio distribution and settle for diminutive exposure. “The Secret of Kells,” a small picture that dwells far from the standards of the mainstream, argues against that reasoning in an era where CGI has eclipsed the prevailing power of hand-drawn cartoons, and finds a quality worth revisiting. This is perhaps the most enchanting and zealous animated endeavor you will see this side of the Pixar lineup: a stylistic and vibrant piece of art that tells a rich story, and does so with an implication that would marvel the finest storytellers of the Hollywood Golden Age. To imagine something this special coming along in a time when theaters are obsessed by the high tech mediocrity of 21st century cartoons is quite revealing. Regardless of where the values may lie, here is a genre that continues to inspire the imaginations of artists of all walks and cultures to immense heights.

Wednesday, August 28, 2013

Man of Steel / **1/2 (2013)

Any movie about a superhero usually begins with the same pointed questions: what are their origins, and how did they come into their abilities? The answers in the “Superman” movies have not always encouraged directors to see them as more than just a suggestive afterthought. “Man of Steel” immediately presents a distinct departure from that sentiment – in a prologue that is both vast and realized, the planet of Krypton is seen in the final throws of a demise that exposes great social unrest. According to a being known as Jor-El (Russell Crowe), the Kryptonians have depleted their planet’s core of essential resources, sentencing its inhabitants to certain doom as their habitat begins to implode. The endeavors of a man named General Zod (Michael Shannon) are stirred to tyrannical proportions by such prospects, and he spearheads a rebel movement to overthrow the existing leaders and steal from them a critical codex containing the genetic blueprints of their civilization. Shoot-outs and fast chases aboard flying starcraft ensue, and then Jor and his wife are seen stowing away the codex on a ship that will carry their newborn son across distant galaxies to a little blue planet that, hopefully, will give him an opportunity at a better life. Unfortunately for the child, those rebels too survive the experience of a dying planet, setting the stage for some sort of eventual confrontation between them.

Monday, August 26, 2013

The Mortal Instruments: City of Bones / *1/2 (2013)

There have been countless pictures featuring actors who basically phone in their performances, but “The Mortal Instruments: City of Bones” is the first in a while in which the screenplay encourages that laziness. Penned by newcomer Jessica Prostigo, the movie plays like one of those film school experiments where everyone on set remains aloof from the material because their drive is dictated by getting class assignments out of the way rather than having passion for the craft. She and her director Harald Zwart find an odd choice to exhibit this behavior for, however: the movie is the first based on a popular series of young adult novels penned by Cassandra Claire, which by definition would suggest that they might have a stake in its success. Instead what we get is a result with a bad case of attention deficit, built around clichés and half-inspired visual and narrative gimmicks in which characters pass through scenes of flashy textures, discuss predicaments with inane dialogue, and occasionally stop to kiss one another when the soundtrack cuts to a pop song.

Friday, August 23, 2013

Hitchcock / *** (2012)

It all begins with a need, they say. Then comes the discovery, sometimes found in the low rumbles of a source off radar. And then the all-important idea: the single thought and purpose that will lay the groundwork for one’s drive. These are the seeds of inspiration that many movie directors go through in that narrow window of artistic limbo between completion of one project and scoping for another, and sometimes they come together with almost divine purpose. One wonders if this is how the real Alfred Hitchcock felt in that time of uncertainty when he went searching for new material after the success of “North by Northwest,” and found a lurid little novel in his hands that fictionalized the gratuitous crime spree of serial killer Ed Gein in the late 30s. The book was called “Psycho,” and the rest was bloody entertaining history.

Thursday, August 22, 2013

Magnolia / **** (1999)

In the haze of late 90s human dramas that observed characters through the cracked lens of pragmatism, fresh faces in the cinema found a playground of golden opportunities. From this threshold came the onslaught of a new generation of ambitious thinkers, paving the way for names like Neil Labute, Lars von Trier, Darren Aronofsky, Danny Boyle and Sam Mendes to show up on movie screens – men who worked within the shadows instead of stepping outside of them, each employing a voice relative to the times and finding tremendous inspiration in the turn-of-the-century paranoia that quietly wove its way through narratives. These were not necessarily cynical stories, but they underscored the vulnerability of their players in a way that removed the gloss and polish of previous decades, and brought them closer to our experiences. Some might say even dangerously close. Just imagine the faces of more optimistic movie artists like Capra or Brooks as they watched a picture like “Trainspotting” or “In the Company of Men”; no doubt their joy would be replaced by looks of shock and crashing feelings of despair.

Tuesday, August 20, 2013

Oblivion / **1/2 (2013)

When a movie engages in the argument of DNA being the source of a human’s memories and identity, one finds very few scenarios in search of plausible conclusions. In the recent “Moon,” those ideas were echoed in meditative passages that refused to be decisive, imploring audiences to consider the uncertainty rather than revel in final explanations. In a more popular example, “Alien Resurrection” featured a story arc of the character of Ellen Ripley being cloned hundreds of years after her death, and the replica seemed to possess vague hints of the original’s memories and feelings. How are these threads of reasoning possible? Are they possible at all, even? The doubt emphasizes the joyous continuity of the great sci-fi fables of our lifetime, echoing the words of Phillip K. Dick or the visions of Stanley Kubrick and Ridley Scott in their desire to ask questions impossible to answer in simple episodes. To reply to them with conclusive reasoning is to defy the core intentions of this genre, which means to leave the discussion open for our inspired minds.

Monday, August 19, 2013

Elysium / *** (2013)

The world of class division and social imbalance in “Elysium” is not one I would ever hope to visit. Sure, that giant circular space station hovering just outside Earth’s orbit is intriguing; using machines to create its artificial atmosphere and solar panels to wall in narrow stretches of man-made land, the wealthiest of human societies find total peace and serenity in this oblique habitat, as if residents of the Hamptons never displaced from home. Their advances in medicine are quite miraculous too, and even a terminally ill patient would marvel at technology’s ability to simply remove all traces of viruses and pathogens by a simple body scan in a “med bay.” But there is a sense of passive acceptance in their perfunctory lives that acts as blinders to the ways of the rest of human civilization, 99 percent of whom still occupy an Earth that is overpopulated, drenched in fatal sicknesses and poverty, and given no hope of improvement. To many of them, the existence of Elysium stands out in the sky like a Utopian vision, a symbol of promise that inspires one to the highest of goals. It never dawns on them that the same palace they idolize could also be the very thing that is turning a blind eye to their needs.

Friday, August 16, 2013

Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter / *1/2 (2012)

“Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter” is the first in what will no doubt be a long and exhaustive trek across the cinematic landscape of well-known historical and literary figures coming to blows with the movie monsters made famous in the golden age of Hollywood. Based on a popular book of the same name, it sets an example now widely embraced by fiction readers of this generation, in which characters from famous stories like “Sense and Sensibility” do battle with sea monsters, or the heroine of “Pride and Prejudice” is caught in a world of zombies. In some meandering way, I suppose, this marriage of genres is a clever gimmick on part of skilled writers wanting to lure aspiring bookworms into the practice of developing knowledge of the classics of literature outside of educational curriculums. Such a ploy is shrewd on their part, but effective for an audience of novices that are easily hooked by the supernatural sensibilities of modern art.

Thursday, August 15, 2013

The Red Violin / ***1/2 (1998)

The obsessive nature of man is stirred by desires of impossible reach – desires to capture perfection, to acquire something greater than the mind can comprehend, and to bask in a glow of inspiration that may open a pathway to unmatched elation. The fault in possessing such aspirations is that the human soul is usually too frail to endure the lessons it must confront. For all the important players in “The Red Violin,” that message is shown within the presence of a singular object that transcends time and culture. Crafted in 1681 by the hands of a gifted violin maker named Nicolo Bussotti (Carlo Cecchi), a remarkable violin – so named in the title because of its distinctive red hue –becomes a physical and emotional current affecting various sets of lives from one century to the next on a journey of divine mystery. It possesses great secrets. And in all instances, it passes from one owner to the next as if a muse meant to inspire them (and their observers) to masterful heights – heights, unfortunately, so great that they bend the will of men and women to equally tragic depths.

Tuesday, August 13, 2013

Melancholia / **** (2011)

Lars von Trier’s “Melancholia” is a symphony of poetry conducted with almost fortuitous precision, the kind of movie that happens not because it was calculated with certain dedication, but because all of its key ingredients come together in the right time and place when its director is emotionally mature enough to assume the material. Few films are as effective at evoking the purely intuitive nature of their directors, but they do exist in rare instances. Think of Werner Herzog’s “Aguirre, the Wrath of God,” or Ingmar Bergman’s “The Seventh Seal.” Achievements of this regard abandon structure and grounding because they are impulses in motion, and are conducive to the development of artists who are ready to step beyond traditions in order to seek transcendence. The journey von Trier has taken to this one immaculate moment has been bold to say the least, but at long last, he has revealed his full ability, and the result is his masterwork.

Monday, August 12, 2013

Lessons from Criterion:

"Antichrist" by Lars von Trier

To make a film as divisive as “Antichrist” in a movie climate that laps up torture and despair at the hands of cruel sadists, Lars von Trier made more statements than he perhaps intended to. Created in a vacuum of professional uncertainty and often described by the director as his “therapy” in very dark personal times, the end result became a hot discussion during its premiere at the Cannes Film Festival in 2009. Some lauded what they saw with thunderous cheers (most of the European press was captivated by its frontal implications) and others engulfed that enthusiasm with equally-commanding boos and lashings (one prominent American critic even branded the material as “worthless,” and questioned the sanity of the Festival board for including it in the competition). The festival went on to even honor the endeavor with an “anti-award” – one of the fewest in festival history – and called the end result an exercise in misogyny. In both extremes, the display became the precursor to similar outbursts of enthusiasm (or repulsion) in the hands of its eventual audience. No person who saw the movie was unaffected by the suggestions it made, and no response lacked passionate conviction.

Friday, August 9, 2013

Joyful Noise / * (2012)

The title “Joyful Noise” is as much a misnomer as you can find when it comes to descriptive movie names. Noise it is, joyful it is not. Somewhere in some dark and quiet room, potentially with sad music playing softly in the background, the person who opted to fund this ill-conceived comedy is sitting in dead silence with his head in his hands, shamed by the same question that all investors who once faced financial ruin have pondered over time: “where did this all go wrong?” Endorsing the movie to any audience with favorable IQ points would be an insult, but there is a certain morbid fascination I uphold in what viewers with some knowledge of church choirs would think of what they see. My gut tells me their reactions would be even more spiteful than mine, and the enthusiasm in those convictions would no doubt be more energetic than anything the filmmakers have conveyed.

Thursday, August 8, 2013

Pacific Rim / *** (2013)

With the Japanese being the primary victims of giant monster attacks over the course of decades in the movies, it’s just as well that they get to be the ones who name the giant creatures who wreak havoc in “Pacific Rim.” Dubbed the “Kaiju,” these giant alien beasts begin making sudden appearances on Earth in the year 2013, causing mayhem and catastrophe along the pacific coastlines in routine intervals before being conquered by military forces, only to be replaced by others much more ferocious than the previous. A voiceover at the start of the picture points to the source of their arrival: a portal nestled at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean which allows beasts from another world to pass from theirs to ours with minimal fuss. But why would they even want to invade us in the first place? By means of educated guesses, we suspect that these alien life forms are simply eager at eradicating the human race for the sake of planetary takeover. Thinking further about the idea of dimensional doorways being the source of movie monsters in general, I half wondered if a similar gate in the Atlantic is what essentially unleashed the creature in “Cloverfield.”

Wednesday, August 7, 2013

The Illusion of Influence

My admiration for Johnny Depp and the dexterity he brings

to his movie roles has been unwavering for decades, but the diatribe he and his

cohorts from “The Lone Ranger” went on during the recent U.K. premiere plays

like a blatant absence of sanity. In the press room, the brains behind Disney’s

biggest flop of the year rallied around director Gore Verbinski and continued

to push their faith in their big-budgeted remake of the famous television

series, but took the argument against its domestic failure up a notch when they

opted to direct the crosshairs of blame onto the critics.

Tuesday, August 6, 2013

Lincoln / ***1/2 (2012)

The opening scenes create a clear distinction: war is not the sole component dividing this society. The man in the tall hat seated in the center of a military encampment stares beyond the piercing rains and sees his supporters trapped in a cycle of building and preparing, mindful of the reality that many will not be left standing alive after the inevitable battles that remain to be fought. Their drive nevertheless is inspiring, and reflects the enthusiasm for the ideals being set forth by the visionary who calls himself the commander-in-chief in these dark and tumultuous times. A young black supporter wanders nearby and reminds the president, somewhat unintentionally, of the importance of the mission: his eyes beaming with a light of hope, he recites the introductory lines of the famous Gettysburg address. For him, and thousands of other slaves who were victimized and persecuted for countless generations before the dawn of the civil war, these words were more than just a call for important change: they were, in essence, the keys to opening the door that had long been shut on a sect of population. The subsistence of these proclamations underscores the greatest desire of all human life, which comes down to, quite simply, freedom and liberty for all.

Monday, August 5, 2013

Lessons from Criterion:

"Ali: Fear Eats the Soul" by Rainer Werner Fassbinder

If German history books must paraphrase the sum of its important contributions to world cinema, all statements begin and end by referencing the country’s two most essential eras – that of “Germanic Expressionism” in the 20s, and the more recent “Neuer Deutscher Film,” which began in the 60s as a way to usher in a generation of thinkers who thought beyond the proverbial boundaries of their culture. In both instances, young aspiring artists were conditioned by the fallout of Germany’s involvement in two World Wars, and under the weighted influence of a social structure seeped in uncertainty, they were eager to embrace the fires of chaos in order to obliterate the illusion of harmony that was used as an oxygen mask.

Friday, August 2, 2013

A Muse of a Different Color

|

| Photographed by Cherie Renae, of Cherie Renae Photography. |

Thursday, August 1, 2013

Silver Linings Playbook / ***1/2 (2012)

The internal conflict that overwhelms the main character in “Silver Linings Playbook” is obvious even before a word is spoken. His eyes shift to and fro with a sense of unease, and the mannered, almost calculated way he speaks to staff and fellow patients within the psych ward he is soon to be released from suggests a knack for exaggerating the truth, possibly because it makes it that much easier for him to stay within the confines of denial. But all will be okay in the long run, he believes, because “Excelsior,” the Latin word for “ever upward,” is on his lips relentlessly when in the face of his heavy-handed reality. Alone, somewhat detached and clueless as to the damage control that will be required in the world he alienated, Pat is ready to face the future head on with absolute optimism. And that means finding a silver lining in all day-to-day situations even if he has to practically beat it out of himself.

Tuesday, July 30, 2013

Django Unchained / ***1/2 (2012)

There is material in “Django Unchained” that is unconventional even by the standards of the notorious Quentin Tarantino, whose movies over the past twenty years have been celebratory excursions through all things eccentric and inspired. Some new energy, or desire, must have possessed him here. After gleefully rewriting history for the purpose of an audacious payoff in “Inglorious Basterds,” no longer does the cinema’s most blunt self-made director seem content on just unscrewing the wheels on the car in the last lap of a narrative racetrack. Now, the cars veer off the track itself long before the first sequence even plays out, and characters are beckoned into the shadows of ambition that provide no promise of anything other than long stretches of stylish violence and dismay. The obligatory touches of quirk coupled with repeated nods to the vengeful nature of spaghetti westerns still exist, but here is the movie in the director’s ever-evolving catalogue that finally arrives at the center of an exhaustive trek through the corners of lurid cinema, marking a critical tipping point in a creative march that suggests, yes, Tarantino’s education is at last complete.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)