During a recent viewing of the astounding “12 Angry Men,” my mind was persistently drawn to another picture from the same era – Alfred Hitchcock’s “The Wrong Man,” also starring Henry Fonda, about a middle-class individual who is accused of a series of burglaries he did not commit. Filmed and released within a year of one another, both movies were parables of a legal system that created vacuums for error, and while the innocence of the plaintiff in Sidney Lumet’s film was up to speculation, the certainty in Hitchcock’s was not; here was in a man who simply was in the wrong place at the wrong time, and bore a striking resemblance to a crook responsible for hundreds of lost dollars at the end of a loaded gun. Their common themes, one might say, reflected an attitude of the times that both filmmakers found strikingly relevant; no greater threat could undermine the security of people than a flawed justice system, especially one that had not yet adopted the values of surveillance or forensic advancement. Yet to consider both movies now in this time of artifice is to marvel at the unwavering power of truth, a tool often weakened in the face of investigative limitations. Was it also diminished by prejudice? Misconceptions? Or was one’s faith in the system simply misplaced? When the director briefly appears in the prologue to announce to the camera that his “true” story is perhaps stranger than most of his own fiction, one is inclined to sense there is equal parts resignation and befuddlement in his voice.

Sunday, May 29, 2016

Monday, May 23, 2016

Lessons from Criterion:

"12 Angry Men" by Sidney Lumet

Released in 1957 on the cusp of Hollywood’s new fascination with hard-hitting legal dramas, Sidney Lumet’s “12 Angry Men” was a film seemingly destined to forever tread the tide of cinematic obscurity. While initial reviews had ranged from middling to respectable, desires for commercial appeal had been set adrift by most box office analysts; the endeavor had not been released to the public under any substantial promotional campaign, and studio executives scoffed at the challenge of marketing a picture that featured only one prominent mainstream actor (Henry Fonda) in the middle of an audience boom for epics and star vehicles. That the movie had also been the filmmaking debut of a small and unknown director of teleplays did little to add to their enthusiasm, inevitably casting his work in a shadow of uncertainty. Yet when one takes part in any discussion about the use of the American Justice system in motion pictures today, nearly every reputable source cites it as a watershed moment for the genre, a stubborn relic that refuses to fade from the periphery of vivid moviegoeing experiences. In some way that has less to do with the premise (an important factor all its own) and more to do with how the characters echo the volatile nature of extreme human behaviors in a state of agitation. These are not actors playing up the parts of fictionalized projections; they are embodying the facets of common middle class men of their era, all of whom must burrow their way through the demand of deciding the fate of a human life in a case where evidence may not exactly paint the clearest portrait of guilt.

Monday, May 16, 2016

Captain America: Civil War / *** (2016)

“Victory at the expense of the innocent is no victory at all.” So goes a key proclamation early on in the third “Captain America” film, made by a weary witness to the catastrophic events that follow an assemblage of superheroes known as the Avengers. His words are more than just a call for accountability on the behavior of physically superior beings in mainstream society – they echo a misplaced undercurrent that I have wondered about in the comic book films as of late, where chaos has run rampant and the fates of nameless victims have lost relevance in the blur of an ambitious foreground. That recurring trend also creates a strange quagmire, I think, for fans of the heroes: how can you support a group of elite and powerful figures when their endeavors to save a world from tyranny come at the expense of flattened cities and countless casualties? When the Tony Stark character shares an early scene with the mother of a man who was inadvertently killed by his team, their interaction penetrates to the most complicated angle of this conflict – no good deed goes unpunished, especially if you’re a person who can flatten buildings with the wave of a fist.

Friday, May 13, 2016

Seven / **** (1995)

Expanding into the reaches of marginal film genres was a defining impulse for the career of Morgan Freeman, a man whose screen presence is usually at the service of plots in search of a voice of reason. The stubborn conviction of formula stories certainly provided him an ample supply of such platforms; as was the case in “Glory” or “Driving Miss Daisy” (two of his earliest successes), he thrived on playing characters that had an underlying edge to them, written from a suggestion that they were the sorts of people who endured through the grind by being honest and assertive when others wallowed in delusion. Why did it take him so long, then, to appear in crime thrillers, which had usually been robbed of protagonists with calm temperaments and informed demeanors? As we watch David Fincher’s “Seven” in hindsight of all the came after, his presence takes on an almost ethereal dominance, as if to suggest he is there because fate insisted his was the only perspective qualified to give such deplorable narrative undercurrents an intellectual meaning. For nearly every movie about a sadistic criminal that would come after, some part of us recalls the careful modulation of words of Detective Somerset, who may be one of the first men in mainstream cinema that dares to ask the question: why do we easily dismiss serial killers as lunatics?

Sunday, May 8, 2016

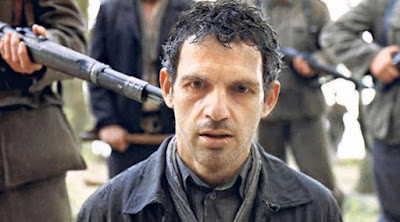

Son of Saul / **** (2015)

The sad and disquieting holocaust tragedy “Son of Saul” compels us to ponder a myriad of difficult questions, but none greater than this: what is it about a person’s face that gives a movie such decisive emotional meaning? The great Ingmar Bergman believed expressions were the passage to one’s very soul – a device that mirrored the pain and confusion of the human experience – and his movie camera frequently studied them as a means in dealing with agonizing moral complexities. If that doctrine rings true in the minds of more modern thinkers, then it is little wonder László Nemes, the impassioned Hungarian filmmaker behind this endeavor, carved his picture in the image of that sentiment. This isn’t a straightforward retelling of one man’s struggle in the hell of a Nazi concentration camp, as a reading of the premise would suggest – it is an observation of behavior that is dictated by a terrifying pattern of military orders, murder and persecution, and how one’s endurance can reduce such realities to a blur of confusion when the hope for a good deed lingers beyond the line of sight of an unending massacre.

Saturday, May 7, 2016

Hello, My Name is Doris / *** (2016)

Like fine wines uncorked from a lengthy shelf life, a great actor has the capability of disappearing from view and then resurfacing with surprising potency, inspiring us to fall in love with their dependable brand of charisma all over again. We seldom recognize the possibility as a reliable prospect, and perhaps that speaks just as much to the narrow focus of modern Hollywood as it does our own cynical expectations. Many of those thoughts crept into my mind as I watched Sally Field on screen in “Hello, My Name is Doris,” a movie she possesses with the utmost zeal. Should we have believed that this brilliant woman, a vibrant presence, would have faded quietly into oblivion? Who’s to say she was not destined to persevere against the ageist trend that dominates the industry? A lengthy departure from film that saw her dabble predominantly in major television dramas has done nothing to diminish any of her abilities, and there are moments in the movie where our admiration isn’t so much about the likability of her character as it is the refreshing candor of its portrayer. “Norma Rae” may have announced the arrival of one of the great screen stars of the 20th century, but here is an endeavor that validates all of those early proclamations in immense clarity.

Sunday, May 1, 2016

Town & Country / 1/2* (2001)

What in heaven’s name were these people thinking? What inclination could possibly possess anyone with a reputable mind to surrender to blatant artistic prostitution? Those are but just two of dozens of pragmatic questions that arise during the experience of watching “Town & Country,” a movie so thoroughly miscalculated and awkward that merely thinking about it causes one to feel robbed of brain cells. And what’s essential for us to consider certainly must have been contemplated tenfold from within; after over two years of exhausting rewrites, reshoots, problematic schedules, misplaced egos and disastrous test screenings, someone at the helm must have known they were overseeing a gargantuan failure, or at least detected that they all were destined for a troublesome launch. But how did it even get that far in the first place, we ask? You would think at some point during a story conference, perhaps, someone – anyone – would have been audacious enough to rally against the incompetence of the dialogue or the disconnect in the human behaviors, well before a single frame was shot. Great amounts of revision certainly didn’t help; what remains on screen inspires us to the height shock and awe, and not for any purpose of redeeming value or unintended humor. Here is such a colossally bad film that there is little wonder in how it failed so catastrophically in the public eye.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)