On a quiet evening in May of 1993, three young boys in a small town in Arkansas were wandering the neighborhoods after school when an assailant abducted, bound and brutally murdered them, and then left their mutilated remains in a ditch in a remote forested area off a nearby interstate. The ensuing events in West Memphis over the following year were of disquieting reality, as details of the crimes were exposed in graphic detail, a community was whipped into a frenzy of fear and anger, and three teenagers were prosecuted for the slayings based on evidence that was perhaps less than circumstantial. That all of this played out in an atmosphere that was rank in overwhelming religious undertones no doubt complicated the matters, but one central question would endure long after the nightmare had ceased: could three relatively docile teenage boys really commit something so heinous, or were they the victims of a hysteria that demanded some kind of finality to a crime too shocking to comprehend?

The movie opens with a chilling series of sequences in which police video shows three bicycles being pulled from the river, and then the shocking sight of three eight-year-olds dumped in a ditch after they are killed, their clothes removed and their skin punctuated with countless cuts and gashes. One boy’s face is masked with dried blood; another is missing pieces of skin, and his genitals are mutilated. In each we see alarming close-ups of faces frozen in a deathly stasis that are cause for almost immediate wincing, but the material refuses to back down. This is the reality of West Memphis, and nothing for them will ever be the same after that terrible day in May.

This is the basis of the monumental “Paradise Lost,” a movie of alarming detail that documents the events just as they happen, and from all the diverging perspectives involved in that brief but gruesome reality that gripped a small Arkansas community for well over a year. Very few documentary filmmakers have the reach to be so thorough in their depiction of the facts, but Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky – the directors – go beyond that expectation and put on display a startling arsenal of the most candid, honest and undaunted experiences of everyone involved in the mayhem, ranging from family members of the victims to the suspects themselves to the very law enforcement involved in their convictions. Imagine what it might be like at the epicenter of a city-wide tragedy having to watch on with clogged interest, and you begin to understand the outlook. Literally no stone is left unturned here (a camera is even present during court room proceedings), and the eerie grasp the movie has over the material leaves behind statements that challenge both our certainty in the events as well as the stability of a town that seems more caught up in emotions and attitude in search of an answer. No wonder, really, the film has endured with generations of impassioned viewers since its HBO debut in 1996.

My familiarity with the endeavor – and most of the details associated with these cases – was insignificant until fairly recently, and their discovery was inspired by the arrival of a dramatized film depicting the events at this year’s Toronto Film Festival. “You have to see these movies,” a colleague wrote to me. “They will change your perception about the legal system.” After a sequenced viewing of not one but three films about these cases, I saw what he was getting at. The first is the most important: the filmmakers descend into West Memphis before the case itself gained national notoriety, and they wander through the material like observers in a psychological catastrophe. Nameless citizens stand anxiously behind yellow tape waiting for an update on three missing boys. News of their gruesome deaths spreads like wildfire, and many are reduced to piles of tears in the streets. The parents of the deceased are paralyzed with shock; some barely know how to respond other than to stare blankly into a space. The local police issue statements that allude to “cult activity” being a possible motive. And then a confession from a teenage kid places him and two others at the scene of the crime, and a populace suddenly becomes a collective lynch mob eager for blood. Some, like the parents of Michael Moore (one of the victims) can only sit back and shake their heads in sorrow; others, like the uber-religious John Mark Byers, stare directly at the camera in order to preach their hatred (“I hope you all burn in hell for eternity!”). And that is all well before the case even reaches the courtroom.

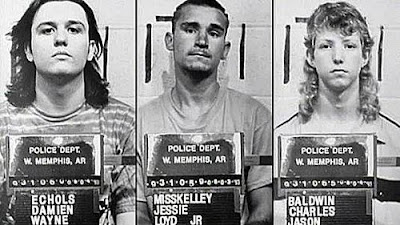

But what of the three accused? The movie’s position is one of uncertainty, but they seem like unlikely candidates for murder based on their personalities. The “ringleader” of the three, Damien Echols, suspects he was singled out based on his black clothing and hair (not to mention a brief dabbling in Wicca), and he treats the reality with certain sarcastic detachment in order to keep the public outcry from unnerving him. Jason Baldwin, whose own arrest may only be grounded on the basis of his friendship with Echols, barely has a word to say, and can’t comprehend the idea that he could be convicted of a crime he didn’t commit; innocence, in his eyes, is the only defense. And Jessie Misskelley, who may have actually been coerced into the key confession that propels the case, never takes his eyes off the floor in the courtroom; he is shy, saddened and simple-minded (and indeed, if you have a reported IQ of 72, are you in full possession of logic if police interrogators are grilling you to the point of exhaustion?).

The movie is ripe with open-ended questions that are left up to individual interpretation. There is no voice-over narration in any of the material, either; only observations, punctuated occasionally with information cards describing events that happen off screen (such as a key moment in which the filmmakers are given a hunting knife as a gift from the stepfather of one of the victims, and there is a tissue sample at the base of the blade that provides an alternate lead for the defense team to pursue). In all scenarios, only one constant emerges: the people of West Memphis are caught up in a sentiment that dismisses all notions of wrong-doing as a work of evil, and the murders of three 8-year-old boys are the warning sign of satanic undertones that exist in their society. There is, of course, no proof of that idea, only speculation. And in utilizing it, the community exposes a naivety that by today’s more informed standards would infuriate the masses. This is seen quite potently in the “occult” angle that the prosecution team pursues; in one critical scene, they put an “expert” on the stand who describes the apparent physical characteristics of those involved in the occult (black fingernails, black hair, black clothing, all of which Damien Echols possesses), and then is cross-examined by a defense attorney who reveals the witness has not taken any actual classes for his credentials. A motion to dismiss the witness’ testimony is denied by the judge, alas; according to him, you really don’t need education degrees to be an expert at some things. I wonder if that distinction included judging murder trials.

Here is evidence that undoubtedly would have been laughed out of most courtrooms in a time or place that wasn’t blinded by belief in mere evil presences. Why was there not a drop of blood or sign of struggle found at the ditch where the bodies were discovered? Why is a serrated knife found at the bottom of a nearby lake submitted as evidence if its edges of the blade are not synonymous with the wounds on the victims? Why was only part of the conversation with Jessie Misskelley taped leading into his confession; what was said prior to that? And if a strange man with blood on his arms showed up at a restaurant near the murder site the same evening that the boys disappeared, why did the police department not link the two? Furthermore, why were the blood samples lost before they were submitted for testing? The irony is that none of these questions seem to matter much to either jury, who convict the three suspects in a climax that leaves audiences bewildered. With no apparent link establishing them to the crimes, the concept of being guilty “beyond a reasonable doubt” seems to emerge from a place of empty sentiment.

Ultimately, however, the movie is about so much more than whether the accused were victims of injustice; it also is about the tragedy of innocent lives snuffed out in cruel ways, about how the masses can huddle together in a blanket of faith while the media feasts on the bloodshed, and about how the need for justice can circumvent the accuracy of a legal system harassed to find the person responsible. For those in some way linked to the fallout of these murders, the emotional toll was significantly greater than what either you or I will probably experience in a lifetime; but for the camera, functioning members of society are reduced to primordial instincts, and lines dividing faith from integrity are broken when the need for vengeance means sacrificing everything (including possible logic) to arrive there. By the end, few are convinced that those three kids are to blame for what they have been accused of, and even fewer are satisfied with the bizarre implication of all gruesome crime looming in the shadow of Satan. What a sad commentary on humanity and the flawed justice system it relies on.

Author’s Note: it is a personal belief that most documentaries come from a place of information that cannot be graded, so “Paradise Lost” is not being awarded a star rating; they are simply irrelevant here.

Written by DAVID KEYES

Documentary (US); 1996; Not Rated; Running Time: 150 Minutes

Cast:

Damien Wayne Echols

Charles Jason Baldwin

Jessie Miskelley

John Mark Byers

Melissa Byers

Pam Hobbs

Jessie Miskelley, Sr.

Gary Gitchell

Produced by Joe Berlinger, Loren Eiferman , Jonathan Moss, Sheila Nevins and Bruce Sinofsky; Directed by Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky

No comments:

Post a Comment