Of the novels that make up J.R.R. Tolkien's "Lord of the Rings" trilogy, "The Return of the King" is the most dynamic and emotionally-driven of the three, boasting both spirit and strain as it plows its way through a series of tense climaxes on its way to a resolution. What gives it such an edge over its predecessors has less to do with specific events, however, and more to do with the fact that readers have become far more invested in the story with time; they care about what happens to their favorite characters and can practically touch the settings with their own fingertips, as if every twist and turn is happening to them as equally as it is happening to the actual participants. That's because the great fantasy literature has never worked simply based on the notion of having characters rush off on quests or getting mixed up in trouble; it has depended on leveling the playing field to a point where the outside spectators can see themselves contributing to actual decisions and outcomes. Anyone, therefore, who has been installed in Tolkien's trilogy knows well the rush of drama that comes from being brought to the end of the journey. It may take much for one to take root in this elaborate material, but it takes a lot more energy to accept the fact that all good things, no matter how inviting or substantial they may be, must come to an end.

Wednesday, December 17, 2003

Looney Tunes: Back in Action / *1/2 (2003)

If there's one thing that Warner Bros. can depend on, it's that there will always be an audience for Bugs Bunny and his cartoon costars. The "Looney Tunes," as they have been popularized as since their inception in the early 1930s, are among the pinnacle cartoon figures of modern pop culture, characters who can be identified simply by walking onto the screen for a split second before saying or doing anything. That's because like Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse, they house the earliest and purest values of Hollywood animators, who in the early days created their creatures out of substance instead of just for the sake of filling an empty story role. To this day, they remain as well-drawn as they have always been, and seeing them show up in the new "Looney Tunes: Back in Action" not only does wonders for nostalgia, but allows us to recall the elements that made them so distinctive in the first place.

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World / * (2003)

The Patrick O'Brian novels about seafaring adventurer Jack Aubrey have amassed so many admirers and enthusiasts in the last 40 years, its fan base could almost easily match J.R.R. Tolkien's in both size and dedication. Small wonder, then, that the stories, rather conveniently, are finding their way onto the big screen just as the saga of Middle Earth's treacherous One Ring is drawing to a close. Could it be that movie audiences have a renewed fascination with ambitious and stylized Hollywood epics, a trend that lost significant steam in the mid-1960s? Whatever the answer, there are still reasons why such productions don't flood the market as significantly as they used to—there simply isn't room or need for all of them. "Master & Commander: The Far Side of the World," the first of an inevitable series of screen adaptations of O'Brian's famous stories, is a rather potent reminder that the most ambitious undertakings won't necessarily add much to the crop. It's an irrelevant, lackluster, dry result that does little but reaffirm the notion that the "Rings" trilogy is all the audience needs right now to satisfy those cravings for bid-budgeted Hollywood epics.

Shattered Glass / *** (2003)

Con artists can get just about anywhere if they have the right knack for putting up elaborate facades. Just ask Stephen Glass, who, in the late 1990s, fabricated over two dozen articles in the east coast-based The New Republic, which prided itself (at least at the time) as the news publication of choice aboard Air Force One. Slick as a dog and every bit as calculating, he manipulated his peers and superiors with a fiery demeanor. But such a task only clouded the initial issue, which was that his stories were too flamboyant and ingenious to be legitimate in the first place. From an outside perspective, simply reading one of his famous pieces has the immediate mark of fiction; sensationalism has always been an escape route for writers without substantial inspiration, yes, but there's a fine line separating the sensational from the absurd, too. Just like the old saying goes: if it's too good to be true, then it probably is.

Wednesday, November 5, 2003

Intolerable Cruelty / ** (2003)

Give a wise man a few dollars and he'll probably invest them into something worthwhile; give the money to the Coen brothers, and chances are you'll watch it whirl down the drain. Those peculiar, ironic directors of films like "Fargo" and "Oh Brother, Where Art Thou?" are heavily influenced by quirks and oddities when it comes to moviemaking — some of it too brilliant for words — but when their style is tuned under the influence of a Hollywood-sized budget, the results can be less than satisfying. Consider their last endeavor "The Man Who Wasn't There," a film noir vehicle saturated by the prospect of being shot in gorgeous black and white—once you strip away the uncanny sense of style, the movie itself lacks personality and rhythm. On the other hand, a film with such subtle traces of financial backing as "Fargo" is quite inverted; though technique isn't exactly cutting edge, the amount of thought applied to the screenplay is so grand that nothing else matters. There is no denying that the Coen brothers are satisfactory directors at the core, but do they truly know what it takes to establish consistency?

Johnstown Flood / **1/2 (2003)

Until a DVD copy of the recently-released "Johnstown Flood" found its way onto my doorstep in early August, I never even knew of such a Pennsylvania-based disaster, much less expected to see a documentary based on one. And yet there it was, an hour-long historical look at an event that might have seemed fabricated had no one been specifically told otherwise. If there is indeed a much greater purpose to the documentary world than just elaborating on major issues for those seeking thorough perspective, then here is a product that tests out some of that wisdom—in the end, no matter how much you think you know about your own culture, chances are there's always something that has been overlooked.

The Matrix Revolutions / *** (2003)

To see the latest (and probably last) "Matrix" installment right on the heels of its sensational predecessor, "The Matrix Reloaded," is to see a solid and exciting finale to the sci-fi series that jump-started a new era of technological and psychological ingenuity. Viewing the movie itself as a completely separate entity, however, the result represents efforts that are far inferior to those that came before. That's because "The Matrix Revolutions" plays less like an actual movie and more like a detached climax; it lacks the ideas that were instituted earlier in the series because it's too busy wrapping up loose ends left over from the second chapter in the trilogy, which made its way onto theater screens earlier this year. No, this is not the brilliant marriage of action and concept we saw with the first two installments in this franchise. But it is, at its core, an entertaining and engrossing action vehicle, and though it tries little in the way of new plot devices, it does manage to keep the eyes intrigued for two hours of solid and well-photographed action sequences.

Mystic River / ***1/2 (2003)

Clint Eastwood's "Mystic River" opens with an event that will inevitably challenge every moral character throughout the movie, a scene in which one of three childhood friends is dragged off against his will in the back seat of a car as his buddies watch on in paralyzed gazes. Two days later, the lad emerges from a nearby wooded area shaken and scarred by the abduction, enough so that it actually prevents him from openly discussing specific events of it with anyone. For some, that kind of detached response is just step one in dealing with the trauma and moving on, but for innocent little Dave, it is like an infected wound that is simply too painful to medicate. The passage of time doesn't do much to help soothe the soars, either, and eventually they evolve into something far more devastating and tragic than even the victim himself could have imagined. He may have escaped his captors, but his spirit never came home with him.

Pieces of April / *** (2003)

Peter Hedges's "Pieces of April" is the kind of movie you have to watch without the slightest cynicism, otherwise you find yourself dismissing a perfectly acceptable story because of a technical shortcoming that nearly buries its virtues. When I refer to this problem, I don't actually mean to dismiss it completely as a flaw, either; for what it's worth, this is the kind of movie that knows what it is doing and genuinely believes the technique is appropriate for the material. But alas it is not; shot on a minuscule budget completely with handheld digital cameras, the film is ugly and shoddy, almost as if the celluloid had passed through a coat of bleach before winding up on the projection reel. Scenes of high emotion are undermined by a washed out exterior, while less important moments seem lifted to much greater importance because they have strangely different contrasts and hues from other surrounding scenes. This is not just a miscalculation for the source material, but a significant distraction as well.

Runaway Jury / ***1/2 (2003)

The typical John Grisham crime thriller has this irritating tendency of assuming that excitement can be spurred by the heated exchange of a lot of legal psycho-babble. As a device for generating thrills, this is as halfhearted an approach as they come. Even the average Joe at a movie theater will tell you that establishing tension depends on more than just characters saying things or making threats; it depends on a combination of elements falling into place, each of them stressing one another in order to generate interest and create buildup without letting ambiguity become implausible blather. With a casual look back at the films utilizing Grisham's novels as source material, one or more of the aforementioned necessities is either misplaced or detached from the setup. In "The Firm," for example, a strong sense of tension is undermined by countless scenes of foolish storytelling, while in "The Client," we get the interesting buildup without the actual final payoff.

Veronica Guerin / *** (2003)

Defining the spirit of a hero conjures up more than just images of stealth and perseverance, but also those of sacrifice and tragedy. That's because most true heroes, particularly in the movies, are martyrs; their attempts to spur change for the better often come at the cost of their own happiness, even when the price is high enough for them to clearly realize the deadly risks involved. Yet somehow, someway, they shrug off the danger and face the odds head-on, seemingly invulnerable to the threats and almost surprised when their own lives are put in potentially mortal danger. Is it foolishness that guides them? Perhaps. But at the core all they want to do is make a difference, a factor that buries every trace of naivety until it's too late.

Friday, September 26, 2003

Jeepers Creepers 2 / *1/2 (2003)

When it comes to sequels, movie reviewers are ordinarily encouraged to revisit an impending film's universe before even thinking about seeing the follow-up, but that alas is a practice I overlooked when it came to observing "Jeepers Creepers 2." According to a stack of promotional materials, my only source of foreknowledge in the inevitable journey to seeing this product, the film's predecessor sets a scenario that is more or less a platform for countless franchise installments; in other words, it suggests that any and all future additions to a series will either a) depend on prior events for any plot development, or b) simply repeat the same exact setup over and over again without adding anything other than higher body counts. We can usually get away with bypassing older series installments if the latter selection is implored (after all, what's the significance in revisiting a series if it is merely repeating itself?), but on the rare occasions that sequels are advancements of older stories, acquaintance with the original premise is sometimes essential.

Matchstick Men / ***1/2 (2003)

Poor ol' Roy just hasn't got a clue. A man married to his work is bound not to have much of a personal life, but when the person in question is actually a very successful manipulator and con artist, you'd expect him or her to have some kind of free time to spend on developing social skills. So is not the case with this reclusive dude, however; aside from being an incessant neat freak who obsesses over the slightest possibility of germs contaminating his environment, he's short-fused, pigheaded and outwardly pitiful to himself and to all those who cross his path. And yet we admire him anyway, because once you peel away the hypertensive demeanor and most of those erratic impulses of his, you have a sweet, charming and lovable guy living underneath. It's not everyday you find yourself rooting for the con man.

Underworld / ***1/2 (2003)

Len Wiseman's "Underworld" launches with a premise that is easily one of the most inspired concerning vampires and werewolves since the creatures themselves first appeared on the big screen. In the murkiest corners of a shadowed gothic metropolis, the familiar horror film adversaries are driven not by bloodlust, but by their own personal struggle to endure. For a thousand years, the movie's heroine tells us in the opening shot, both the vampires and the werewolves (referred to as "Lycans" through most of the picture) have been in a heated war with each other, one that reached catastrophic proportions for the werewolves at one point when one of their most important leaders was killed by the opposition. Thus, in a state of fragmentation, the Lycans scattered into the city as the vampires assumed control of the highest point in the food chain, and though their control has gone fairly unchallenged since the days when the werewolf society was crippled, fear of a resistance persists and the vampires are encouraged to destroy every last breathing creature they can find.

Friday, August 22, 2003

Gigli / 1/2* (2003)

If life has been difficult for director/writer Martin Brest in the recent years, then there are plenty of reasons to see why. Once considered one of Hollywood's most promising filmmakers, he quickly developed a notoriety for making the most ambitious bad movies of his day, big-budgeted stinkers that featured big-name actors reciting amateurish dialogue from screenplays that rambled on and on without any sense of direction or purpose. His last and most damning endeavor of all, the overlong and pretentious dud "Meet Joe Black," not only exercised that declining general perception of his talent as a moviemaker, but reinvigorated the tradition of the bad movie itself, too, setting a benchmark for all those beyond who could waste millions of dollars and countless frames of celluloid as they were tossing turds onto unsuspecting moviegoers. Many have lived up to that precedent, others have surpassed it—but being the first prominent figure to do such a thing is a feat that shouldn't go ignored, and Brest maintains that reputation even when his peers aim higher and land much lower than he has. He is a modern Ed Wood with a much larger bank account.

Grind / ** (2003)

They say it takes a certain knowledge of a subject to truly empathize a movie based on it, but I'm guessing it will take more than that to show any sort of genuine interest in a movie like "Grind." With this rugged excursion into the world of skateboarders and their constant uphill battle into making it as professionals, one must not simply have basic affection for the sport itself, but patience with the film's other elements as well, like a story that takes nearly forever to actually get off the ground and characters who don't begin to reveal themselves until long after the adventure is underway. Much like the ramp that serves as a platform for these kinds of extreme sports participators, this is the kind of movie that is in an uphill battle with itself before it finally finds the courage to soar. By that point, we're not exactly bored or too exhausted to care, but the thrill factor is decidedly thinned and our interest is too minuscule to warrant an enthusiastic reaction.

Lucia Lucia / **1/2 (2003)

The movie narrator is expected to be nothing if not consistent with the audience's perception of events, but unless that person is the kind that takes material seriously, viewers will often run the risk of falling into traps or blindly following false pretenses. In "The Opposite of Sex," a movie about a girl who begins to understand life by reassessing the twisted way she lives it, Christina Ricci played such a person, a girl whose cynical demeanor made it impossible for us to accept her version of the events at face value, as she spouted on about irony and fabricated scenarios so that certain events played out without clear distinction to the viewer. In that picture, nothing was necessarily as it seemed, and yet every manipulative impulse was relevant to the characterization, as it allowed the person in question to be seen in a light separate from what other characters could see. In endeavors like this, the one who is telling the story can offer a lot more dimension if he or she comes equipped with their own arsenal of insecurities and personality flaws; that way, they can reveal themselves to the audience in a way that they couldn't ordinarily do by simply participating in the plot.

Open Range / *** (2003)

It doesn't take much of an investigation to see why movie westerns died out following John Wayne's demise. Without the charisma and the energy that the Duke pumped into it during his 60-year career, the genre lost its only source of redemption, inevitably exposing it as the cliché-ridden world of limited ideas that it had become in the years since its inception. Of course, no one bothered to argue about those traits in old Hollywood because the concept of being formulaic was still too primitive for anyone to really care. But when Wayne passed on in the late 70s, so did the wall shielding the eyes from the truth. Like the documentary, a western is only as good as the one who carries you through it, and there is no denying that few (if any) could compare to the way in which Wayne kept fans of the films interested and caring, at least towards the end when the concept grew tired.

Monday, July 28, 2003

The League of Extraordinary Gentleman / * (2003)

Only halfway into the summer of 2003, and the most dreadful studio blockbuster of the year finally reaches the multiplexes. "The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen" tramples across the screen like a stampede of destructive elephants, wrecking everything in its ferocious path without necessarily intending to do so in the process. And that's a sad prospect, because when the movie opens, the intriguing premise suggests that there is, indeed, a valuable product hidden beneath the coarse exteriors. But then without hesitation, the movie goes nuts and becomes this giant web of chaos, sometimes even at points when we least expect it to. In this league's "extraordinary" universe, there is no rule book, no presence of logic, and no factor of intelligence whatsoever; it exists merely on its own plane of stupidity, feeding off ineptitude at such an alarming pace that it's a wonder any kind of filmmaker could salvage a product worthy of a wide theatrical release.

Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl / *** (2003)

"Pirates of the Caribbean" is probably the most ambitious B-movie ever made, a rollicking spectacle of color and adventure that strives continuously to be more than what it could ordinarily get away with. In a few ways, that pitch of energy makes the experience so much more enjoyable than anticipated; in others, it simply keeps the film moving on longer than it has to. In fact, by the time the movie passes the ever-dreaded 2-hour mark, it no longer becomes a question as to how the movie will end, but when it will end. Sword fights, treasure hunting and pirate lingo exist here as visual pleasures that don't know when to cease; they simply move on and on without a regard to time or fuel. The fact that the name Jerry Bruckheimer precedes the credits as executive producer is only the first clue to this distracting misfortune.

Sinbad: Legend of the Seven Seas / ** (2003)

The generations that were raised on 2D feature animation have long since dissipated into the age of CGI, leaving behind a medium still so pervaded with promising ideas that it's discouraging to see most of them go almost completely ignored at the box office. Consider Disney's last traditional feature cartoon "Treasure Planet," a dazzling adventure with visual spectacles outside of the studio's norm—produced on a budget estimated to be between 140 and 150 million, the film took in a measly 30 million dollars during its initial theatrical run last fall, making it one of the genre's biggest commercial disasters of the recent past. Meanwhile, the current animated champ, the PIXAR-produced computer cartoon "Finding Nemo," looks about ready to upset "The Lion King" as the most successful of all time in feature animation, a feat that seemed impossible even to the CGI giants like "Shrek" and "Toy Story."

Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines / ***1/2 (2003)

During the opening moments of "Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines," the voice of our hero John Connor informs the audience, somewhat reluctantly, that the "future is not yet written." This, however, is not the voice of the same John Connor who has accepted a past plagued by memories of time-traveling machines both sent to protect and destroy him; this is the mentality of a full-grown man detached from reality, hopping from one location to the next with minimal social contact in hopes that denial will make all the trauma of his rocky life disappear. But try as he might, those dark times still follow him around like glaring physical scars, and the fact that he tries so hard to hide them only prevents him from leading the life he so clearly hopes is not ordained by any specific destiny.

Friday, June 27, 2003

28 Days Later / **** (2003)

"28 Days Later" begins with three animal rights activists breaking in to the Cambridge primate research facility, their purpose as clear as crystal when a series of cages scattered across the room reveal apes being confined for some kind of scientific experimentation. With another strapped to a table at the opposite end while background television sets drop in and out of activity with various local news stories, their game plan is quick and specific, even though the animals themselves begin to exhibit ballistic behavior at the mere sight of outside activity. For them, the behavior is just a sudden reaction from their presence, but for a scientist who accidentally wanders into the lab while they're preparing the release of the creatures, it signifies something much more dangerous. "You can't release them!", he demands fearfully. "They're infected!" With what, exactly? When one intruder asks that question, the man's eyes merely stares back with a harrowed gaze, his shaky voice replying, rather enigmatically: "...Rage..."

Charlie's Angels: Full Throttle / 1/2* (2003)

The three beauties behind the action-pumped guises of Charlie's Angels are victims of the oldest crime against women in film: becoming dimwitted sex objects without ever seeming to care. They flaunt themselves around on screen in a sly yet alluring manner, outwitting jealous rivals and dangerous enemies through physical moves that would make characters from "The Matrix" feel jealous, and then stop briefly to fix their hair and check their makeup before moving on to a different task. This might have been tolerable if the camera actually cared about anything other than cleavage, but alas is does not. Every time one of these girls bends over or flexes a muscle, the lens is up close and personal to capture as much bare skin as it can, sometimes even using the slow motion technique in order to stretch the length of time in which their seductive poses last. Whatever motivates the filmmakers or the audience to endure 106 minutes of this stuff, it is far below the potential of actresses like Lucy Liu, Cameron Diaz and Drew Barrymore, women who have made a lasting impression on celluloid without having to be brainless sex kittens in the process.

Dumb and Dumberer / * (2003)

Ever get the feeling that you will probably dislike a movie only after a couple of minutes of seeing it play out on screen? This is exactly the kind of emotion that manifests during the rather painful introduction of "Dumb and Dumberer: When Harry Met Lloyd," the prequel to the very successful idiot comedy from a few years back. A series of character introductions pass onto the celluloid with a quirky thrust, but instead of chuckling or even smiling at what material is thrown at us, we stare off without so much as cracking a smile. The scenes are not funny. The scenes that follow are not funny. The scenes that follow still are still not funny. The movie is so laughless that only four notes needed to be recorded on my notepad during the entire screening: after the first 20 minutes, I scribbled down "not very funny"; 20 minutes later, "still not very funny"; 20 minutes more later, "not funny at all"; and finally, after witnessing the conclusion, "painfully unfunny in every way." This is the kind of comedy that doesn't even deserve to be associated with its own genre.

Hulk / *** (2003)

Ang Lee's "Hulk" is the most character-driven of the recent comic book screen treatments, an ambitious special effects movie in which every crucial plot movement is dictated more by physical and psychological impulse rather than the flashy imagery or camerawork. That doesn't necessarily mean it is a better picture than its near cousins, but it is probably a more thought-provoking one; unlike the recent "X2," or even the overlooked "Daredevil" from earlier in the year, this is the type of work that not only works as a visual showpiece, but an in-depth personality inspection as well, strictly utilizing the latter element to drive the narrative beyond the standard plot convictions expected of a super-hero film. It probably helps matters, furthermore, that the movie's own "hero" is decidedly more challenged than most other beings of his arena have been. No, he isn't one of those many gifted creatures who devotes his life to fighting crime or making the world a livable place simply because he is able to; he is a cursed individual with endless internal conflict, a person who periodically caves in to the pressure of emotional pain to reveal a side of himself that could as easily harm him as much as it could benefit him against an enemy.

Friday, June 6, 2003

Bruce Almighty / ** (2003)

It takes a distinctive kind of screen talent to come across on celluloid as vividly as Jim Carrey does, but when one is dealing with a movie like "Bruce Almighty," not even the most zealous demeanor is safe from being subjected to mediocrity. Here is a premise that literally screams the actor's widely-known name, its quirky narrative devices and offbeat comic ploys echoing the essential ingredient behind every one of his past hits almost instinctively. Unfortunately, that's where the movie makes its most fatal error, too; by assuming that viewers are still thirsty for "Ace Ventura"-like pranks and bodily fluid humor, among other less-than-inspired things, it unwittingly runs out of steam barely before the first hour is even over. At least such ploys in the past in Carrey films have resulted in some sort of enthusiastic response, be it greatly negative or positive. This time, however, we simply don't care enough to even warrant a tired groan.

Finding Nemo / ***1/2 (2003)

The warm and inviting visuals that catapult us into the world of "Finding Nemo" instantly evoke one of the oldest of childhood pleasures: that of watching curious little water-based creatures swim strategically through decorated aquariums like adventurers seeking buried treasure. The amusing pastime, at least on an surveying level, is as innocent a thing to a kid as playing with friends or having ice cream on a summer day, but for those of us who grew up to accept the time-consuming challenges of fish-keeping, the cycle of life for our little undersea pets is anything but a straightforward journey, plagued by nearly all the universal laws of nature that have been established for virtually every living being on this planet. Just imagine, though, how all those poor little fish must feel amongst our own frustration, not knowing where to turn or what to do in the established parameters of their ever-changing homes. In this new Disney film, a colorful canvas alive even at the farthest edges helps pitch these important realizations to the younger viewer, who accept that little fish can be "cute" but don't quite understand the level of dangerous intricacy that surrounds them behind glass and in the sea. Surviving, it seems, is their real adventure.

The In-Laws / *1/2 (2003)

"The In-Laws" opens with a scene that misleads the very source material it is introducing, by enlisting the Michael Douglas character, Steve Tobias, in a confrontation with spies and double agents wielding rapid fire guns as he tries to pull off some sort of elaborate heist before making a quick and painless getaway. The James Bond-style opening is, we later realize, just an innocent distraction before the core story gets underway, but it nevertheless paves the road with a surface that the whole movie, alas, is only too eager to follow. This isn't a comedy about colorful families and their dysfunction, as it probably should be, but a spy caper wrapped around two middle-aged men, neither of them very interesting, who predictably don't get along until they are thrown into a maddening climax that requires them to work together. This might have been potent stuff if the material were dedicated to the premise, but the narrative is indecisive, and in the process the film forgets to be funny.

My Little Eye / 1/2* (2003)

Being conventional is never a direct goal for anyone who sets out to conceive a notable cinematic product, but "My Little Eye" may very well be the first film I have seen in ages that intentionally exercises all the big horror movie clichés in order to process its plot. What's even scarier, perhaps more than any frame of it that materializes on screen, is that the movie doesn't even know why it is going this route: if it's trying to give twisted new spins to old ideas or is simply too dimwitted to manufacture new ones. Even the film's technique is a ponderous approach, purposely styled after the "Blair Witch" phenomenon to, I guess, add a touch of visual realism to the concept. But there is almost nothing authentic or even captivating about the end result itself; during its tiresome 95-minute screen run, we never feel involved, we're never fascinated, and we're not interested in what happens to anyone or why it happens to them in the first place.

Thursday, May 15, 2003

The Matrix Reloaded / **** (2003)

There is a certain fondness to be felt during trips to the local multiplex lately, especially when passing through those front lobbies where studios tend to tease their upcoming releases like fishermen showing off fancy new lures. In the far corner of this shameless promotional gallery is a poster for "The Matrix Reloaded," one of two sequels arriving in theaters this year to a now-infamous sci-fi masterpiece, with an enigmatic tag-line that reads at the bottom, almost frivolously, "How far down does the rabbit hole go?" Ah, but if the answer was obvious, would that still have warranted anyone from devising follow-ups to this now-legendary sci-fi adventure? Surely not. Here is a world with so much left unanswered, so many things left unexplored, it has never really escaped our consciousness. It is all around us. It has pulled you into its web of complexity almost without even trying. This Matrix hasn't merely recaptured you—it has never left you.

Friday, May 9, 2003

Daddy Day Care / *1/2 (2003)

Ask the average man about raising a child, and chances are he will redirect your inquiries to a woman. If that's the sort of generalization that most of today's male population still happily embrace, then it's unlikely that any of them will find a shred of appeal in "Daddy Day Care," a film in which fathers decide to watch and manage the kids of strangers before realizing how lackluster their parenting skills are with their own youngsters. Indeed, as asked during an important dialogue exchange during the early half of the picture, "are men not capable of taking care of a kid the same way a woman can?" Perhaps so, perhaps not. In either case, the answer is probably too simple to even deserve the focus of an entire movie, especially one containing the likes of Anjelica Houston and Eddie Murphy in front of the camera.

Holes / *** (2003)

He who said you should not judge a piece of work based on its title sure said a mouthful. Andrew Davis' "Holes" is a movie that comes scurrying off the screen with one of the single most childish and unpleasant names in recent memory, outdoing even the horrendous stupidity of such endeavors as "Piglet's Big Movie" and "Bulletproof Monk" without even seeming to try as hard. The knee-jerk reaction to hearing it is to assume the worst of the product itself, and yet as the movie is being absorbed, suddenly we're forgetting all about our initial reservations and actually enjoying ourselves. Disney has not generally been a studio to leave pleasant surprises for audiences in the form of live action book adaptations (think for a moment about that horrendous "Tuck Everlasting' debacle last fall), but here they have broken the mold with what is perhaps one of the most interesting and amusing family adventures of the recent past. Holes may dominate the events of the plot, but the final product is far from being one itself.

X2: X-Men United / **1/2 (2003)

The stories of the X-Men and their intricate adventures in a world with instinctive to fear and hate them have always been a source of constant fascination in the ever-changing comic book market, but even more fascinating has been Hollywood's challenge of filtering that rich 40-year history of the series into a collection of two-hour action films aimed squarely at casual moviegoers. For those of us more familiar with the material than, say, the average theater attendee, the questions often outweigh the anticipation: who, for instance, decides what plots get covered in these endeavors? Who decides what characters to include and how to introduce them? Who or what doesn't quite make the cut? The answers maybe simple, but the brains behind Twentieth Century Fox's inevitably-ongoing franchise aren't immediately thinking about the cravings of hardcore series purists. No, these movie mutants are not a homage to those comic buffs who have waited patiently for years to see these plots and players make the leap to the big screen; they are colorful summer blockbusters designed to appeal to an audience that doesn't expect to know a thing about the source material.

Monday, April 14, 2003

Anger Management / *1/2 (2003)

Trying to make sense of the material in "Anger Management" is almost like trying to understand Adam Sandler's entire career: the longer you attempt it, the more of a headache you wind up with. For nearly three fourths of its overlong running time, the movie holds up a bizarre and baffling pretense in which simple behavior spawns major overreactions and harsh punishments from others, sometimes seeming so severe that it's a wonder no one makes a point of challenging it beyond an amazed stare. And then the movie plays its nasty trick; no, not the kind that sheds new light on previous stuff, but the kind that makes us wonder why we even had to endure it all in the first place. The only thing missing from the climax, in fact, is someone jumping out in front of the hero and saying "Smile, you're on Candid Camera!"

The Core / **1/2 (2003)

You know it from the title. You can see it in the trailers. Even before you've gawked at two finalized seconds of "The Core" on screen, you know it is the most blatantly silly disaster film ever made. The notion is imbedded into our heads before the theater even goes dark. And why wouldn't it be? Any movie teasing the idea that human technology has advanced fast enough to allow men to venture deep into the cores of this complex planet has little plausibility going for it. Of course, credibility isn't exactly essential to disaster movies to begin with, but even then, certain borders have still been drawn and stepping over them can possibly be more damaging than beneficial.

A Man Apart / ** (2003)

One of "A Man Apart"s early scenes features a specifically stressed dialogue exchange in which a commanding officer instructs the men in his anti-narcotics team, one member of which is played by Vin Diesel, to drop their firearms before descending into a deadly drug bust to capture an infamous cartel leader. They follow through on the order because, well, it's the safer scenario. Then we cut to the next scene where we witness both the good guys and the bad guys engaged in major gunplay, thousands of rounds of ammunition piercing everything in sight as a result. Emphasizing this specific event wouldn't ordinarily be necessary at the start of a film review, but in this movie, it underlines not only an exact logic problem with one scene, but with the whole film itself. Like a chain reaction, this kind of implausible subtext repeats itself over and over again throughout this endeavor, depleting us of basic patience and robbing the film of its essential function to make a shred of sense.

Phone Booth / **** (2003)

It's not very safe to be on a phone anymore. Just ask anyone who gets stuck in traffic next to a driver with his ear glued to a highly-distracting cellphone, or the guy who takes a call inside the house when he should be keeping an eye on his kids at the deep end of the swimming pool. Consider the working woman who is receiving obscene phone calls because of the way she dresses, and think of the teenagers who are cleverly manipulated into a death trap by murderous men who ask with a certain rustic charm in their voice, "do you like scary movies?" The phone itself isn't necessarily a culprit to these kinds of conflicts—after all, would Alexander Graham Bell have invented it if he knew it would cause so much dismay?—but as the movies continue to tell us, they can be merciless magnets for deception and betrayal, easily turning an ordinary day into one we'd rather forget ever happened.

Friday, March 21, 2003

Boat Trip / zero stars (2003)

So here it is already, just three short months into the year—the single worst movie of 2003. "Boat Trip" hurls itself onto the screen like an endless diatribe of amateurism, slashing its way through one bad scene after another before it ultimately sinks into the murky depths of nothingness. The movie is an insulting, pathetic and tone-deaf assault on our senses; to watch it unfold from beginning to end is to feel imprisoned by the screening room it is playing in.

Dreamcatcher / *1/2 (2003)

Promotional trailers tend to build great expectations without even revealing the smallest narrative clue, and that is the situation—or more appropriately, the downfall—with Lawrence Kasdan's "Dreamcatcher." In the recent weeks, television screens and theater projectors have been bombarded by swiftly edited teasers that are almost too incoherent to grasp the basic context. They are deliberately ambiguous, converged on rapid camera shots and pulsating thuds in the soundtrack as they shamelessly maneuver every plot angle they can. Normally this approach can suggest shortcomings, but we as moviegoers are too optimistic to live by such ideals, so when people enter the movie theater to finally see the final product, they will be going in not with worry or reservation, but with genuine excitement. Only in the end, however, will they realize exactly why all the advertising spots lack an outline of the premise.

Mommie Dearest / *1/2 (1981)

"Mommie Dearest" is a book by a woman whose motives seem questionable. During the closing moments of the film adaptation, which examines the life of Joan Crawford through the eyes of her adoptive daughter Christina, the narrator shakes her head in disbelief when her mother's last will in testament reveals no inheritance for either her or her younger brother. "Mommie always gets the last word," he explains, to which Christina answers with a certain determination in her voice, "does she?" Having not read the book itself, immediate instinct is write off this closing reaction as a plot device simply meant to tie the picture to its source material. But if it is more than that? What if that moment reflects Christina's entire reasoning behind the initial purpose of the novel? Certainly, under that kind of scenario, it is aptly possible that any truth told about Ms. Crawford and her malicious behavior is anything but the whole truth.

Friday, March 14, 2003

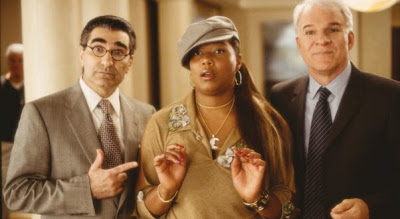

Bringing Down the House / ** (2003)

"Bringing Down The House" is a movie under the inane delusion that old and ignorant white people can be the least bit amusing when they're clumsily trying to act like hip and young black people. I can live with Steve Martin spouting out dialogue like "Yo Mama," but words still escape me after watching the lovely Joan Plowright transformed into an uptight and bitter little socialite, who in one scene unforgivably mocks slavery in front of Queen Latifah and then later finds herself sitting between two black men at the neighborhood bar puffing on a joint. Moments like these defy the essence of comedy not because they lack luster or even ambition, but because they're basically just clichéd plot contraptions designed to simply further along the formula. In a movie as obvious as this, we know exactly what is expected of people at specific intervals, and it's never very funny.

Dark Blue / ***1/2 (2003)

Sergeant Eldon Petty Jr. is a cop at nonstop war with both internal and external forces, not the least of which is his own distorted sense of ideology. Produced in an atmosphere tattered by the hysterics of rebellion and the blood of the innocent, he's at the core of the biting commentary so vividly utilized in Ron Shelton's cop drama "Dark Blue," emerging as a man without personal motive or free will because the system he is trapped in refuses to accept its slaves as thinkers or individuals. We don't automatically assume he was easily snared into this behavior, and yet it's difficult to imagine any other possible scenario or outcome. After all, what kind of person would you be if you had surrendered your dedication over to a world where corruption and politics were the only two integral driving forces?

Tears of the Sun / *1/2 (2003)

"He was trained to follow orders. He became a hero by defying them."

- Tagline from "Tears of the Sun"

It's a shame that A.K. Waters didn't learn anything about humanity before he descended into the bloodstained jungles of Nigeria, otherwise he might have spared the audience from enduring the painful first half hour of "Tears of the Sun." A the leader of a Special-Ops unit sent into the African nation to rescue selected American citizens from an impending "ethnic cleansing," you'd expect him to immediately emerge as someone who has some sense of priority other than merely getting a mission completed. So is not the immediate case, however, and like a confused child, the movie tiptoes around him for a good 30 minutes before it allows him to make any kind of personal epiphany. And even then, things still don't begin to line up the way they should.

- Tagline from "Tears of the Sun"

It's a shame that A.K. Waters didn't learn anything about humanity before he descended into the bloodstained jungles of Nigeria, otherwise he might have spared the audience from enduring the painful first half hour of "Tears of the Sun." A the leader of a Special-Ops unit sent into the African nation to rescue selected American citizens from an impending "ethnic cleansing," you'd expect him to immediately emerge as someone who has some sense of priority other than merely getting a mission completed. So is not the immediate case, however, and like a confused child, the movie tiptoes around him for a good 30 minutes before it allows him to make any kind of personal epiphany. And even then, things still don't begin to line up the way they should.

Willard / * (2003)

The twisted and mangled images that serve as the opening credits to "Willard" are not just exemplary to a movie of this nature, but also some of the most fierce and visually striking ones to have been scrawled across the movie screen in the recent years. Part-Tim Burton and part-Tarsem Singh in their modern yet primitive delivery, they fittingly tease the product's eccentric ideas without throwing away too much information or robbing the audience of its impending anticipation. Normally the movie itself would only emphasize the greatness of its introductory scenes, but alas, so is not the case with this rather bizarre result. There is a great idea in the fabric here somewhere, no doubt, but it gets lost, and it gets lost very fast.

Friday, February 28, 2003

Oscars 2003: Nominee Reactions

February 28, 2003

If there's one thing worse than being unfair, it's being predictable; that, at least, is the popular theory as far as award shows are concerned. And when the results for this year's Oscar nominees were revealed early on Tuesday, February 11, the only logical thing anyone could do was leap to their feet, throw their heads back in disbelief, and wonder with a certain vexation in their voice, "I waited all this time just for THAT?"

If there's one thing worse than being unfair, it's being predictable; that, at least, is the popular theory as far as award shows are concerned. And when the results for this year's Oscar nominees were revealed early on Tuesday, February 11, the only logical thing anyone could do was leap to their feet, throw their heads back in disbelief, and wonder with a certain vexation in their voice, "I waited all this time just for THAT?"

Daredevil / *** (2003)

If the audience indeed knows more about the super-hero essence than most filmmakers do, then it will be interesting to see if anyone can explain the mysterious physical chutzpah behind Daredevil, a crime fighter who leaps great distances between buildings, drops hundreds of feet from the air without the use of specific assets or interference to break his falls, and never seems to injure himself as a result. We can get away with most masked protagonists performing these types of stunts because the evidence is always there to enforce it; Superman's superhuman abilities allow him to fly, for instance, while Batman and Spider-Man suspend gravitational limits because they have nifty gadgets that allow them to. And the mutants of "X-Men" can fly too because, well, they're mutants. With this particular comic book hero, however, no specific explanation or hint of reasoning is applied to the concept, other than the assumption being incredibly acrobatic is achieved simply by someone going blind after an accident with spilled chemicals.

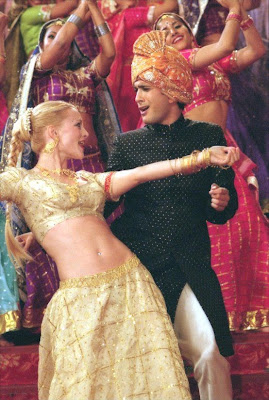

The Guru / 1/2* (2003)

The funniest moment in "The Guru" comes just a hair before the closing credits begin to roll, when a fireman rushes over to a nearby church, interrupts a wedding, and professes his undying love for the groom. The comical timing of this particular moment is so spot-on and alive, it's a wonder that it even exists at all in a film that is almost completely devoid of any sense of laughter. For a good long hour, the movie continuously holds the impulse of delivering its jokes in an uncomfortable and unamusing way, when suddenly a gag like this erupts from out of nowhere. A bit shocking, of course, but it saves this incredibly bad endeavor from falling into that ever-so-dreaded "zero star" club, if only just barely. Don't make too much fuss about it, but know that there is, at least, a shred light at the end of this long and dark tunnel of amateurism. As for the movie itself—it's complete trash, a clunky, idiotic, laughless and amateurish collection of scenes targeted to people who have the intellect of mattress springs. Standard defects of an idiot romance plot, including the notion that any guy can get every woman in a room simply by pretending to be someone else, garnish nearly every frame of celluloid, but the picture only wishes it could maintain characters with any level of low-end intelligence. Every face that passes through the camera lens, in fact, is wasted; the screen personas we have to endure aren't just clueless morons, but dissonant ones as well. At least most idiots in these kinds of plots pop a few brain cells every now and then.

The Jungle Book / **1/2 (1967)

Of all the ideas and arguments that Rudyard Kipling conveyed in his ambitious literature, the one thing that he was never able to answer clearly was why Mowgli the man cub wanted to stay in the jungle. The very idea that a simple boy can flourish on the notion of living life among ferocious lions, tigers and bears (oh, my!), even after being raised by wolves, is not exactly the most plausible explanation for any young adventurer, after all; in fact, countless stories about naive little boys or girls at least give the heroes some basic sense of knowledge or instinct, even if it's slightly misguided. Kipling's motivation behind the Mowgli persona in his "The Jungle Book" doesn't necessarily have that forethought; his protagonist is a basic archetype for absent essentials, a rowdy, foolish and inept tyke who refuses to realize his own limits of strength and wisdom, even when he is staring directly into the eyes of a tiger who is born to destroy him.

The Jungle Book 2 / *1/2 (2003)

Disney's "The Jungle Book 2" is a flea market of cheap ploys and meaningless ideas designed to rob parents of hard-earned money, an inane excursion into such lame and forgettable territory that it barely has the thrust to occupy a video store shelf, much less a theater screen. And yet there it is, sucking life out of the projector room as if anyone observing it could feel remotely engaged by its endless mediocrity. The excuse? The only one, I gather, actually seems to have been a goal of the mouse house for many recent years: to cash in on name value rather than administer any kind of product with a shred of merit. It certainly doesn't help matters that this is a follow-up to a less-than-stellar feature cartoon to begin with.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)