“Demon House” is a well-made film study about little of consequence, fashioned from a scorching creative eagerness that seems held back unnecessarily by a fear of visual or thematic excess. Given the familiar groundwork of the premise, that’s hardly a surprise; when it comes to any number of stories about evil forces haunting the living – however true or fictional they claim to be – a great risk persists in exploiting their suffering for the benefit of shocking an audience. But anyone going into Zak Bagans’ endeavor may yearn for the possibility of a happy medium: something between a balance of jolts intercut with perceptive discussions about what may be causing the quiet chaos in these lives. For a good while things gradually move towards that direction, as Bagans, an apparently skilled investigator, involves former eyewitnesses in a descent into the mysteries of a Midwest house filled with supernatural energies. But by the end we are no closer to understanding – or caring about – the source of these evils or the suffering they inflict on others. If a conventional horror film shows people slowly unravelling by the strange events going on in their homes, here is one that settles on raising an eyebrow or two before droppings its subjects in the maw of successive boredom.

Showing posts with label DOCUMENTARY. Show all posts

Showing posts with label DOCUMENTARY. Show all posts

Saturday, March 24, 2018

Tuesday, February 28, 2017

Unearthed and Untold: The Path to Pet Sematary (2016)

Prior to a chance viewing of the new documentary “Unearthed and Untold: The Path to Pet Sematary,” it had escaped my notice that any sort of significant fanbase existed for Mary Lambert’s 1989 adaptation of the famous Stephen King novel, about a burial ground that curses its victims to evil undeath. Even as a teenager, easily amused by the audacious antics of the most leaden horror films, here was a movie that had no sort of power or prominence; it seemed to lumber around on screen much like many of its awakened monsters, half-dead and lacking a conclusive goal beyond bleak undertones and ordinary bloodshed. But that experience of a viewing, I freely admit, had come during an onset of more exploitative genre values, when I was less interested in the straightforward pitches. Was I simply missing something that others were freely savoring? The implication of a revisit stirred deeply as I observed the case being mounted of its great power over a plethora of devoted followers, many of whom turn out to pitch their product in ways that ought to make enthusiastic Hollywood promoters envious. Here is a living document about people who treasure this lost little film so deeply that they never once reference the poor reception that came after, which is suggestive of one of two prospects: either the early audiences were too out of touch to comprehend its value, or those who adore King’s menacing yarn are doing so out of a devotion that makes them oblivious to cinema’s conventional measurements.

Sunday, December 25, 2016

Lo and Behold, Reveries of the Connected World (2016)

A statement comes late in Werner Herzog’s “Lo and Behold, Reveries of the Connected World” that frames the predicament of the times: “The system was designed for people who trust each other.” Those words are spoken by one of the key architects of what we now know as the Internet, a series of connections that began life in the halls of UCLA in the late 60s, back when servers were the size of coffins and the idea of sending immediate messages to great distances was an absurdity out pulp science fiction. But those dreams fueled the engines of a handful of great thinkers in those formative years, leading to an audacious task that culminated on October 19, 1969, when the first word was sent across hundreds of miles of electronic transmission: “Lo” (though it was supposed to be “log”; the system crashed before the final letter came across). The mantra “Lo and Behold” can certainly be used to describe a plethora of technological breakthroughs (and indeed has), but in those days the revolution belonged to only a fragment of people: those who had faith, conviction and loyalty to the movement, decidedly opposite of the perspective of today’s world. What is a mere person living in the here and now supposed to feel when he hears about these details, long after the origins of cyberspace have been blurred and the net is seemingly in control of vitriolic bullies who are capable of inflicting great harm with words and actions?

Tuesday, December 20, 2016

Honest Man: The Life of R. Budd Dwyer (2010)

The first time any young journalist hears the name R. Budd Dwyer it usually occurs during introductory reporting curriculums, when the discussion shifts from writing styles and plunges into the troubled waters of ethics. Once thought to be the leading point of an argument about appropriate newsroom conduct, his very public suicide in front of television cameras has come to rest in the margins of a convoluted history in media decency, especially in the wake of a post-9/11 world of bombings, massacres and civilian beheadings. But it persists, no doubt, because there remains almost no similar conduct for people to compare it to; as such, his is a situation frozen in the shocking embrace of controversy, and a constant source of ambiguous political arguments that would like to erase his strange existence from memory. Shameless voyeurs, however, have preserved his notoriety even more than those fascinated by the puzzling circumstances leading to that tragic day, and easy is the opportunity to search the internet for those final moments, relentlessly plastered all over video feeds. Some may initially wonder if “Honest Man,” a documentary about his troubled political career, would even have been relevant if his last act had not continued to reverberate with perverse allure. Is there anyone left that cares more about the context of that moment than the disquieting inevitability of his lifeless body slumping down in front of a room full of cameras?

Thursday, December 15, 2016

Trespassing Bergman (2013)

In the turbulent waves off the coast of Sweden rests the small island of Fårö, a patch of land that has been the source of constant discussions amongst film buffs and connoisseurs of cinema. On its shores is, we soon discover, the house that Ingmar Bergman called home during the last decades of his life, though few knew where it stood; until his death, its whereabouts remained the closely guarded secret of nearby locals, who feared their most treasured (and secretive) icon would have his privacy undermined by opportunists eager to exploit it. But now the secret has emerged, and film directors far and wide have an awakened interest to wander into the private rooms of his compound, no doubt to gain a sense of his profound essence. Was his vehement privacy as fascinating as his immense body of work, or is there a far more profound undercurrent driving these men and women towards the doorstep of their secretive teacher? When the great Alejandro González Iñárritu wanders into a meeting room and is nearly driven to tears by the power of the moment, it serves to anchor the sentiment of his defining thought: “If cinema were a religion, this would be Mecca, or the Vatican.”

Monday, December 5, 2016

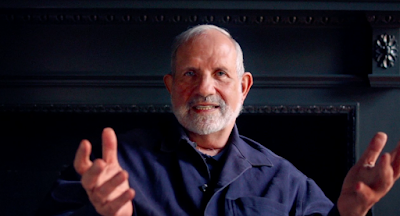

De Palma (2015)

Like most 20th century directors working in the wake of the golden era, Brian De Palma’s sense of craft was not so much a divine creation as it was an enacting of the rich experiments of Alfred Hitchcock. Such wisdom is cursory to any serious record of modern filmmaking, and “De Palma” – the new documentary about his notorious career – begins with a discussion about “Vertigo,” the most direct of his Hollywood allegories. “What he was doing,” De Palma describes, “was creating these romantic images and then killing them off. And that’s what we as directors do all the time.” It is a precious morsel countless others have discussed in unison with their laborious practices, and certainly Hitchcock’s most treasured film is regarded as autobiographical for most, but do his lessons reverberate as consistently as they should? The famed creator of “Dressed to Kill” doesn’t believe so; in a two-hour sit-down that involves crawling through his catalog one picture at a time, the most persistent of points is how Alfred’s shadow has been so dimly cast by those working within his traditions, unless you happen to be him. Perhaps that says more about the subject at hand than those who have freely abandoned the structure of their important ancestors, but far be it from any fascinated observer to interrupt the lines of thinking of one of the more popular creators of the medium.

Friday, July 22, 2016

Into the Abyss (2011)

There are two decisive moments towards the beginning of Werner Herzog’s “Into the Abyss” that left me in the inertia of sobering contemplation. The first involves an interview with a prison warden who oversees the comfort of death row inmates during their final minutes; as they are strapped to the table and prepared for lethal injections, his is the face that they will see last, looking down on them with only the offer of empathy in their transition to another plane. Some are grateful for the opportunity of a kind gesture in those moments, and in a confessional monologue he suggests a sense of complicity in their executions; these are human lives regardless of their misdeeds, and doing a job that contradicts those beliefs reduces the value of his soul. Herzog seems to echo these sentiments in the following scene when he comes face-to-face with Michael Perry, a death row inmate in Texas who is just eight days away from his own fatal punishment. “I don’t’ have to respect you or even like you,” he warns his interview subject. “But I don’t believe in capital punishment. I don’t believe you should be killed.”

Saturday, March 12, 2016

Triumph of the Will (1934)

Among the hundreds of endeavors of the 20th century that helped define the intricate language of cinema, two in particular were made from the fuel of dangerous personal ideologies. The first was D.W. Griffith’s “The Birth of a Nation,” and the second was Leni Riefenstahl’s “Triumph of the Will.” Both movies represented a time when historical doctrines could (and often did) disrupt the social progress of their audiences, and yet through them a few of the most revolutionary technical achievements were realized – some that would even go on to set the tone for nearly all filmmakers that were to follow. But to watch them now and regard their aesthetic triumphs is to struggle with the context in which they are used, sometimes to an end that creates alarming moral uncertainty. Can we suspend that which we are at odds with for the sake of admiring the indelible techniques that were born from their ambitious frames, or must we, indeed, consider art as an impossible measure when it is done in the provision of evil deeds?

Monday, February 8, 2016

The Wild Parrots of Telegraph Hill (2003)

The rhetoric of commoners would have you believe that animals only occupy the personalities we attach to them, but more perceptive minds know better: they can sense the gears of attitude lurking underneath a trajectory of common instincts and silent routines. Part of what attracts us to such creatures – be they pets or otherwise – is that they know how to hold their own in a world of conventional disinterest, often catching our notice by acting in such a way that is indicative of some kind of internal spark. Sometimes that comes in the form of relentless affections, other times strength or defiance. The constant is that there is a necessity in them to be noticed, especially if it relates to their very survival or comfort. How perceptive they must be to have so thoroughly sharpened their associations with human beings over the centuries, especially as it has been instrumental to their endurance in a world that continues to offer new dangers at every given moment.

Sunday, January 25, 2015

Blind Spot: Hitler's Secretary (2002)

In the winter of 1942, a young impressionable face came into the inner sphere of Adolf Hitler with simple aspirations of steady employment. Her name was Traudl Junge, and at age 22 all her worldly concerns came down to basic security, especially as Germany came under the rule of a regime that sought to, from an inside perspective, enhance the national workforce. A co-worker at the Chancellery had heard that the Fuhrer was seeking a private secretary and suggested that she apply for the position, and after excelling at a typing test she was whisked away into the wilderness along with a small cluster of other female applicants, where Hitler was privately obsessing over military orders in one of his many bunkers. She had never seen the dictator outside of political rallies or propaganda news reels, but at the center of her line of sight she discovered a courteous and mannered personality – far from the fiery oratorical genius that the public saw so regularly. In many ways, that was just as dangerous as it was disarming; Junge was the oldest child in a family without a male parental figure, and to her his almost fatherly sense of delicacy with the applicants was a refreshing quality, an aspect that seemed to fill a quiet void in her to be coddled like an affectionate child. It never dawned on her through the course of her employment that her boss led a life of dubious distinction, nor did she come to realize the depth of the atrocities he committed until long after the flames of war had dissipated.

Thursday, July 17, 2014

Hitler's Children (2011)

Five names, five lives forever cast in the shadows of evil. Their faces are hard-worn from existences that seem almost otherworldly, their expressions indicative of countless years of brooding and self-loathing. Who are they? What significance do they hold? Has their experience lead them to outright detachment? They are some of the last descendants of the Nazi empire, and coursing through their veins is the blood of a legacy that will forever haunt them, torture them, and subject them to certain social exile. That they have spent their entire lives atoning for the sins of their ancestors is critical in the study of their troubled lives, but why should they have to go through all of that now, so long after the dust has settled? Are the horrors of our parents and grandparents so potentially horrific that they could, quite possibly, reverberate into the histories of those who come long after?

Monday, July 7, 2014

Life Itself (2014)

The unsung hero of Steve James’s “Life Itself” is a rare force even by the standards of effective fiction. It is not Roger Ebert, the brilliant movie critic of the Chicago Sun-Times, but rather his wife Chaz, a woman whose capacity for love left behind resounding echoes in the life of a man who might have faded into darkness without her. To see her present for the final stages of his life is to witness the endearing patience of an angel; while her emotional struggles remain mostly private, her commitment to his care is steadfast, and the camera is even present in a moment when they both have a striking but calm disagreement over whether he should be walking up stairs after being discharged from a hospital stay. “You need to trust us,” she advises, even when his clenched fists indicate stubborn protest. How did she manage to tread so calmly through the lengthy wilderness of a frail and dying mate without resorting to outright emotional exhaustion? The answer is not as important as the reality, which goes to the heart of meaning in Ebert’s third act of life: when illness leaves one crippled beyond repair, it takes someone strong-willed to provide unending support and compassion, just as it does to fight the disease with all one’s might.

Wednesday, December 11, 2013

Grizzly Man (2005)

The greatest mystery of man often lies in the choices he makes, and Timothy Treadwell created perhaps some of the most ambitious riddles one could imagine. For thirteen consecutive summers, the shy and offbeat nomad left the human world behind and went to live in the company of the wildest of animals: large and dangerous grizzly bears in the Alaskan peninsula, many of which had spent their existence so far outside of human contact that he seemed to occupy space in their unrestrained existence as a lone alien. Social awkwardness made him an outcast, while the seeming peace and tranquility of the wilderness inspired buried passions. But what was the purpose of his consistent desire to distance himself from human interaction? What did he see in the grizzlies that gave him purpose? What do hours upon hours of video documentation show us, other than the dogged dreams of one who fell victim to a false idealism about ferocious predators that exist only to feed and survive?

Friday, September 20, 2013

Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory / (2011)

*(star rating not relevant)*

So here is where their nightmare comes to an end. After 18 years of falsified imprisonment, legal battles, unrelenting suspicion and a documentary filmmaker’s camera as their only link to the outside world, the West Memphis Three arrive at the center of “Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory” having learned the harshest lesson about our flawed legal system, and their reward is their own freedom. But at what cost? Two decades of their lives have been lived in isolation for ludicrous reasons, a devastated community spent all their emotional energy on the wrong targets, and the deaths of three eight year olds have gone without justice because an incompetent police force was too careless in their pursuit of facts. And even after the turmoil, none of those involved in the false convictions ever shows the slightest hint of spine; they resolve to their pompous rhetoric that those convicted were done so in a clean case, and the state’s eventual decision to free them based on reduced sentences instead of full exoneration is a spit in the face. Seldom has a film inspired so much dislike in viewers towards the very system designed to protect them.

So here is where their nightmare comes to an end. After 18 years of falsified imprisonment, legal battles, unrelenting suspicion and a documentary filmmaker’s camera as their only link to the outside world, the West Memphis Three arrive at the center of “Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory” having learned the harshest lesson about our flawed legal system, and their reward is their own freedom. But at what cost? Two decades of their lives have been lived in isolation for ludicrous reasons, a devastated community spent all their emotional energy on the wrong targets, and the deaths of three eight year olds have gone without justice because an incompetent police force was too careless in their pursuit of facts. And even after the turmoil, none of those involved in the false convictions ever shows the slightest hint of spine; they resolve to their pompous rhetoric that those convicted were done so in a clean case, and the state’s eventual decision to free them based on reduced sentences instead of full exoneration is a spit in the face. Seldom has a film inspired so much dislike in viewers towards the very system designed to protect them.

Thursday, September 19, 2013

Paradise Lost 2: Revelations / (2000)

*(star rating not relevant)*

The unanswered questions at the end of “Paradise Lost” were the kind that could inspire not only a need for a follow-up documentary, but indeed an entire political movement. In “Paradise Lost 2,” three teenage boys who were tried and convicted in 1994 of a grizzly series of child murders in Arkansas are nearly five years into their prison sentences, and occupy camera frames like mere shells brow-beaten by a due process that failed them. The perplexity of their convictions was instrumental in the creation of a non-profit support organization that is centralized in the second documentary, in which supporters of the “West Memphis Three” take on operative roles in an appeal process that would overturn the conviction of Damien Echols before a proposed death sentence is carried out. Anyone who saw the predecessor with an open mind can easily see why: in a legal climate that was beginning to use DNA and forensics as keys to unlocking the secrets of heinous crimes, how was it even possible that three relatively calm teenagers could be found guilty of murders that they could not be linked to scientifically?

The unanswered questions at the end of “Paradise Lost” were the kind that could inspire not only a need for a follow-up documentary, but indeed an entire political movement. In “Paradise Lost 2,” three teenage boys who were tried and convicted in 1994 of a grizzly series of child murders in Arkansas are nearly five years into their prison sentences, and occupy camera frames like mere shells brow-beaten by a due process that failed them. The perplexity of their convictions was instrumental in the creation of a non-profit support organization that is centralized in the second documentary, in which supporters of the “West Memphis Three” take on operative roles in an appeal process that would overturn the conviction of Damien Echols before a proposed death sentence is carried out. Anyone who saw the predecessor with an open mind can easily see why: in a legal climate that was beginning to use DNA and forensics as keys to unlocking the secrets of heinous crimes, how was it even possible that three relatively calm teenagers could be found guilty of murders that they could not be linked to scientifically?

Tuesday, September 17, 2013

Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills / (1996)

*(Star Rating Not Relevant)*

On a quiet evening in May of 1993, three young boys in a small town in Arkansas were wandering the neighborhoods after school when an assailant abducted, bound and brutally murdered them, and then left their mutilated remains in a ditch in a remote forested area off a nearby interstate. The ensuing events in West Memphis over the following year were of disquieting reality, as details of the crimes were exposed in graphic detail, a community was whipped into a frenzy of fear and anger, and three teenagers were prosecuted for the slayings based on evidence that was perhaps less than circumstantial. That all of this played out in an atmosphere that was rank in overwhelming religious undertones no doubt complicated the matters, but one central question would endure long after the nightmare had ceased: could three relatively docile teenage boys really commit something so heinous, or were they the victims of a hysteria that demanded some kind of finality to a crime too shocking to comprehend?

On a quiet evening in May of 1993, three young boys in a small town in Arkansas were wandering the neighborhoods after school when an assailant abducted, bound and brutally murdered them, and then left their mutilated remains in a ditch in a remote forested area off a nearby interstate. The ensuing events in West Memphis over the following year were of disquieting reality, as details of the crimes were exposed in graphic detail, a community was whipped into a frenzy of fear and anger, and three teenagers were prosecuted for the slayings based on evidence that was perhaps less than circumstantial. That all of this played out in an atmosphere that was rank in overwhelming religious undertones no doubt complicated the matters, but one central question would endure long after the nightmare had ceased: could three relatively docile teenage boys really commit something so heinous, or were they the victims of a hysteria that demanded some kind of finality to a crime too shocking to comprehend?

Wednesday, November 5, 2003

Johnstown Flood / **1/2 (2003)

Until a DVD copy of the recently-released "Johnstown Flood" found its way onto my doorstep in early August, I never even knew of such a Pennsylvania-based disaster, much less expected to see a documentary based on one. And yet there it was, an hour-long historical look at an event that might have seemed fabricated had no one been specifically told otherwise. If there is indeed a much greater purpose to the documentary world than just elaborating on major issues for those seeking thorough perspective, then here is a product that tests out some of that wisdom—in the end, no matter how much you think you know about your own culture, chances are there's always something that has been overlooked.

Friday, January 10, 2003

Bowling for Columbine / ***1/2 (2002)

Ever since a group of teenagers descended the halls of a high school in Colorado on April 20, 1999, the subject of violence has been a painful and sometimes sluggish debate among the inhabitants of modern society. A legacy that initially founded the United States of America to begin with, violence has always been imbedded in the public's psyche, persisting even in times when the fear of it was much greater than the actual threat itself. But to what extent does that trait manifest into a living beast and consume its host? Does the media provide an easy outlet for it to take charge? And whose to say that any specific person or event is to cause for it unfolding? Columbine forced us to consider these difficult questions extensively, although we still aren't any closer to appropriate answers.

Monday, December 24, 2001

The Endurance / **** (2001)

"There is nothing that can crush a man as to see his dreams crumble to the dust."

- Dialogue from "The Endurance"

A reference is made early on in "The Endurance" in which the narrator (Liam Neeson) refers to the voyage depicted in the film as the "last great journey in the heroic age of discovery." Immediately the mind is flooded with memories of high school history classes, when the majority of us were taught about the perilous but exciting journeys of explorers like Hudson and de Leon, who sought after, and eventually found, pieces of land that few human eyes had seen before. Much less extensive, however, is our knowledge in regard to the 1914 expedition of famed explorer Ernest Shackleton, who, only months before setting sail on his ill-fated adventure, placed an ad in the local British newspaper asking for volunteers to undertake the dangerous, potentially life-threatening task of crossing the entire Antarctic continent on foot—something that had yet to be done. How could most of us miss this piece of history? It's not as if the story is lacking in detail; in fact, "The Endurance," a fascinating new documentary, provides the viewers with enough specifics to almost make them scratch their heads in amazement.

- Dialogue from "The Endurance"

A reference is made early on in "The Endurance" in which the narrator (Liam Neeson) refers to the voyage depicted in the film as the "last great journey in the heroic age of discovery." Immediately the mind is flooded with memories of high school history classes, when the majority of us were taught about the perilous but exciting journeys of explorers like Hudson and de Leon, who sought after, and eventually found, pieces of land that few human eyes had seen before. Much less extensive, however, is our knowledge in regard to the 1914 expedition of famed explorer Ernest Shackleton, who, only months before setting sail on his ill-fated adventure, placed an ad in the local British newspaper asking for volunteers to undertake the dangerous, potentially life-threatening task of crossing the entire Antarctic continent on foot—something that had yet to be done. How could most of us miss this piece of history? It's not as if the story is lacking in detail; in fact, "The Endurance," a fascinating new documentary, provides the viewers with enough specifics to almost make them scratch their heads in amazement.

Friday, December 8, 2000

The Art of Amalia / *** (2000)

Behind every great voice in music is a marvelous force possessing it, and "The Art Of Amália," a documentary from Bruno de Almeida, acquaints us with a pair that will never be forgotten… unless you are from the United States. Readers from other countries will have undoubtedly already heard her name by now; elsewhere, Amália Rodriguez, whose astonishing and successful career lasted for 60 years, is already seen as a legend among peers.

She was a Portuguese singer born into a low-class neighborhood of Lisbon in 1920, and at age four was already being asked to sing for the neighbors. In 1939 she began a career as a nightclub singer, captivating audiences with a seductive voice that melted even the coldest hearts, and into the 1940s a recording and movie career were already beginning to take shape. On home turf, her records and movies broke several records, while abroad, listeners slowly started catching on to the depth of her alluring persona.

She was a Portuguese singer born into a low-class neighborhood of Lisbon in 1920, and at age four was already being asked to sing for the neighbors. In 1939 she began a career as a nightclub singer, captivating audiences with a seductive voice that melted even the coldest hearts, and into the 1940s a recording and movie career were already beginning to take shape. On home turf, her records and movies broke several records, while abroad, listeners slowly started catching on to the depth of her alluring persona.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)