Like a substantial ratio of my readers, I don’t leave 2016 with a sense of relief or accomplishment – I walk away nursing significant mental wounds. Among recent annual passages that carry with them an arsenal of perplexing human experiences, few could be considered as volatile – or indeed as troubling – as what went on over the course of the last twelve months, when social structures were rattled by startling political fallout, world violence reached a new facet of severity, and entertainment industries faced rather troubling dichotomies. It was also the year of the death of celebrity – both literally and figuratively. As famous names from the reveries of the past faded from mortal grasp, others lost their hold on their very reputations, in a time when the lone successor seemed to be corporate entities intent on exploiting the hard-earned dollar of the escapists and the feeble-minded.

Saturday, December 31, 2016

Friday, December 30, 2016

Rogue One: A Star Wars Story / *** (2016)

The first act of “Rogue One: A Star Wars Story” is the frenetic embodiment of the Hollywood machine, a collection of scenes so relentless and overdone that they provide us little time to grasp the scope of their events – unless you are ingrained enough in the mythos of George Lucas’ universe to possess a thorough comprehension, I suppose. Those are the luckiest viewers, in a way, because their sense of exhilaration is likely amplified by their connection to the material, even beyond the mere notion of a movie like this existing at all. But what can be said for the rest of us who don’t own the cliff notes version of the premise, and must observe closely to attempt and piece together the fragments of the conflict? This new stand-alone chapter to the ongoing “Star Wars” saga is an anomaly that will at first seem insufferably distant. There are early moments that involve wondrous sights and notes of nostalgia, but most are sidelined by a central narrative arc that gives little time to characters or their personal experiences. Only later, once an idea has finally lodged in our mind of what everyone’s role is, do things come together well enough to satisfy the more intellectual urges of the audience. The thing about established franchises is that as much as you think you know, so little of it matters when the gears move into new positions.

Thursday, December 29, 2016

In Memoriam, 2016

I am compelled to make a few remarks about the loss of Carrie Fisher and instead am driven to expand the focus, thanks in part to the rather surprising death of Debbie Reynolds, her mother, just a day after she herself succumbed to a heart attack. In a year of so many losses and a tremendous tone of shock, the simultaneous demises of both a mother and daughter just 24 hours shy of one another is unprecedented – an event so unsettling that even those who are removed from the mourning process must regard the occasion with some level of confusion. Peers and admirers on social media have taken to the internet to denounce this troubling year as a source of disgust, perhaps, because it has been clouded by memories we desperately want to forget. But entertainment figures, for better or worse, are symbols of an idealism we treasure in our minds; when they produce good work, it becomes something meaningful. And when they die, we are compelled to react with sorrow not because we knew them personally, but because their work provided us a roadmap towards self-discovery.

Sunday, December 25, 2016

Lo and Behold, Reveries of the Connected World (2016)

A statement comes late in Werner Herzog’s “Lo and Behold, Reveries of the Connected World” that frames the predicament of the times: “The system was designed for people who trust each other.” Those words are spoken by one of the key architects of what we now know as the Internet, a series of connections that began life in the halls of UCLA in the late 60s, back when servers were the size of coffins and the idea of sending immediate messages to great distances was an absurdity out pulp science fiction. But those dreams fueled the engines of a handful of great thinkers in those formative years, leading to an audacious task that culminated on October 19, 1969, when the first word was sent across hundreds of miles of electronic transmission: “Lo” (though it was supposed to be “log”; the system crashed before the final letter came across). The mantra “Lo and Behold” can certainly be used to describe a plethora of technological breakthroughs (and indeed has), but in those days the revolution belonged to only a fragment of people: those who had faith, conviction and loyalty to the movement, decidedly opposite of the perspective of today’s world. What is a mere person living in the here and now supposed to feel when he hears about these details, long after the origins of cyberspace have been blurred and the net is seemingly in control of vitriolic bullies who are capable of inflicting great harm with words and actions?

Tuesday, December 20, 2016

Honest Man: The Life of R. Budd Dwyer (2010)

The first time any young journalist hears the name R. Budd Dwyer it usually occurs during introductory reporting curriculums, when the discussion shifts from writing styles and plunges into the troubled waters of ethics. Once thought to be the leading point of an argument about appropriate newsroom conduct, his very public suicide in front of television cameras has come to rest in the margins of a convoluted history in media decency, especially in the wake of a post-9/11 world of bombings, massacres and civilian beheadings. But it persists, no doubt, because there remains almost no similar conduct for people to compare it to; as such, his is a situation frozen in the shocking embrace of controversy, and a constant source of ambiguous political arguments that would like to erase his strange existence from memory. Shameless voyeurs, however, have preserved his notoriety even more than those fascinated by the puzzling circumstances leading to that tragic day, and easy is the opportunity to search the internet for those final moments, relentlessly plastered all over video feeds. Some may initially wonder if “Honest Man,” a documentary about his troubled political career, would even have been relevant if his last act had not continued to reverberate with perverse allure. Is there anyone left that cares more about the context of that moment than the disquieting inevitability of his lifeless body slumping down in front of a room full of cameras?

Friday, December 16, 2016

The Devil Wears Prada / *** (2006)

In the conventional sense “The Devil Wears Prada” is about a woman who finds herself at the mercy of a demanding boss and does everything possible to earn her approval. In a more conscious perspective, it takes on added meaning – namely as a metaphor for our work-obsessed culture and the growing divides between professional and personal value systems. The heroine at the heart of the matter is the embodiment of that example, and certainly there are moments where her struggles are exploited for the shallow exercises of a standard comedy plot, but why doesn’t it end there? Why does her situation persist so glaringly after the jokes fade and the characterizations erode? Because her life reverbs with the same struggles and contradictions that affect most in the American work force, where it has become a perfunctory routine to abandon personal space and mental safety nets. More serious or satirical contemplations would have burrowed down to the root cause of that irony, but this movie is far less concerned with reasons than it is with the ramifications. And that’s ok, you might say, because the surface of the matter is potent enough to engage our emotional investment, and the characters identifiable enough to sell this pitch with some level of relatability.

Thursday, December 15, 2016

Trespassing Bergman (2013)

In the turbulent waves off the coast of Sweden rests the small island of Fårö, a patch of land that has been the source of constant discussions amongst film buffs and connoisseurs of cinema. On its shores is, we soon discover, the house that Ingmar Bergman called home during the last decades of his life, though few knew where it stood; until his death, its whereabouts remained the closely guarded secret of nearby locals, who feared their most treasured (and secretive) icon would have his privacy undermined by opportunists eager to exploit it. But now the secret has emerged, and film directors far and wide have an awakened interest to wander into the private rooms of his compound, no doubt to gain a sense of his profound essence. Was his vehement privacy as fascinating as his immense body of work, or is there a far more profound undercurrent driving these men and women towards the doorstep of their secretive teacher? When the great Alejandro González Iñárritu wanders into a meeting room and is nearly driven to tears by the power of the moment, it serves to anchor the sentiment of his defining thought: “If cinema were a religion, this would be Mecca, or the Vatican.”

Monday, December 5, 2016

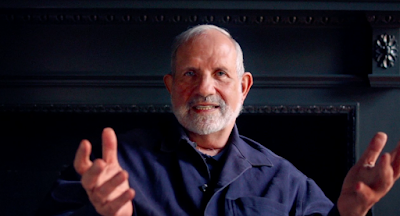

De Palma (2015)

Like most 20th century directors working in the wake of the golden era, Brian De Palma’s sense of craft was not so much a divine creation as it was an enacting of the rich experiments of Alfred Hitchcock. Such wisdom is cursory to any serious record of modern filmmaking, and “De Palma” – the new documentary about his notorious career – begins with a discussion about “Vertigo,” the most direct of his Hollywood allegories. “What he was doing,” De Palma describes, “was creating these romantic images and then killing them off. And that’s what we as directors do all the time.” It is a precious morsel countless others have discussed in unison with their laborious practices, and certainly Hitchcock’s most treasured film is regarded as autobiographical for most, but do his lessons reverberate as consistently as they should? The famed creator of “Dressed to Kill” doesn’t believe so; in a two-hour sit-down that involves crawling through his catalog one picture at a time, the most persistent of points is how Alfred’s shadow has been so dimly cast by those working within his traditions, unless you happen to be him. Perhaps that says more about the subject at hand than those who have freely abandoned the structure of their important ancestors, but far be it from any fascinated observer to interrupt the lines of thinking of one of the more popular creators of the medium.

Sunday, December 4, 2016

Arrival / ***1/2 (2016)

In times when audiences are trained to be enamored by special effects and simplified narrative patterns, “Arrival” is an unusual discovery: a movie that requires us to think beyond the polished surface and contemplate our own place in the universe. While stories revolved around this theme have been exercised abundantly in the science fiction medium over the years, usually they have been to the service of gratifying the momentary senses rather than stimulating the recesses of the human brain. But those paying very close attention to what is occurring within the frames of Denis Villeneuve’s new endeavor will not be walking away with basic assumptions or criticisms – they will be too occupied by the underlying philosophies that have inflicted their thought process, all brought to the surface by perceptive dialogue and a free-form plot structure that considers the very concept of space and time. Minds like Stanley Kubrick and Steven Spielberg knew we were starved for the discovery of deeper meanings in the milieu of dazzling images, but now the movies find themselves leaping audaciously past the domain of earthly assurances to penetrate the membrane of the very cosmos we pass energy through.

Wednesday, November 30, 2016

Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them / **1/2 (2016)

The most elusive of assets in any yarn about whimsical adventure is a writer’s confidence in the material: the assuredness that words and actions have profound ramifications towards a story arc and its characters. Those that lack such an assertion usually become lost in their own inspiration, and rarely offer any sort of significance other than vague interludes of wonder. The new “Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them,” a film within the “Harry Potter” universe that arrives just as the demand for franchise consistency has awoken in the hearts of moviegoers, is of the latter distinction – certainly ambitious in scope and filled with images as enchanting as they are sharp, it rarely seems to know what it has in mind for the ambitious events that are destined to play out. Instead there are only rough connotations for us to rely on; it tells the story of Newt (Eddie Redmayne), a former student of Hogwarts who has arrived in New York carrying a suspicious briefcase filled with magical creatures from the wizarding world to, I suppose, research their bizarre behavior without overreaching influences. Unfortunately, chaos ensues in the presence of an unknowing witness and Newt’s creature are set free in the city, just as the divide between human and magic worlds runs dangerously blurred.

Thursday, November 24, 2016

Doctor Strange / ***1/2 (2016)

There is a wide array of sensations one is apt to experience while watching the new “Doctor Strange,” but the most inexplicable of the arsenal is an unflinching sense of plausibility – the idea that something so seemingly absurd or above the trajectory of audience absorption can feel so thoroughly believable when spied through zealous camera lenses. A basic reading of a plot synopsis certainly contradicts that assumption, and no wonder: the story, about a brilliant doctor who is crippled in an accident, goes on a mystical retreat, discovers astral projection and literally learns how to bend time seems like nothing more than self-indulgent fantasy. But Scott Derrickson, the motivated filmmaker behind Hollywood’s latest excursion into the pages of colorful comic books, takes an approach far more cognizant than most others would, and what emerges on screen far exceeds the cynical expectations of what we routinely offer this genre. Certainly the details have a familiar air to them – the visuals echo “Inception,” the premise recalls elements of “Batman Begins” and the characters are reminiscent of those contained in “The Matrix”, for example – but so infrequently do such things come together in the service of such an engrossing story, much less a mere suggestion of intrigue.

Sunday, November 20, 2016

Moonlight / **** (2016)

The two most important memories in Chiron’s life occur on a beach: one early on when a man acting as a parental figure teaches him how to swim, and one in adolescence when he shares a private encounter with a buddy from school. Both moments are catalysts that allow uncertain eyes to peer beyond the shadows and see a lost part of one’s identity, but observant members of the audience will sense their significance stretching beyond simple narrative agendas. Perhaps that is because their underlying intent is substantiated by the profound depth of writing, which tells the story of a sad introvert whose dueling personal distinctions make him an unwanted target of peer bullying. Perhaps it comes down to the riskiness of the ideas, in themselves a reach for any endeavor piercing the membrane of the mainstream. But it is the fact they exist at all in the walls of the same movie that persists as the undeniable force of wonder. The heartbreaking candor at work in Barry Jenkins’ rich character study amounts to some of the most effective dramatic intensity of the year – no question about that – yet rarely has such a story allowed these details to shape the surface so vividly, especially in the midst of a frontal confrontation with the harrowing prejudices that plague those within their own isolated worlds.

Monday, November 14, 2016

Denial / *** (2016)

Most arguments about the validity of historical events originate from a flaw in the details, and none have thus far been discovered that would alter most of our personal feelings about the atrocities of World War II. A lifetime’s worth of stories and photographs are all that remain of the horror of the Nazi era, for instance, but with them rests a certainty that seems impossible to negate, even from the perspective of those completely removed from the prospect of research or understanding. But in some circles is the pessimism to challenge the very notion of the existence of the holocaust itself – an implication that one’s failure to document an important observation (or to point to a superficial flaw, like the design mechanic of the construction of a camp) must automatically negate the fact that so many people were systematically killed by German fascists. Those sorts are the kind of people who passively nod with the likes of David Duke, once quoted as saying that “we must free the American government from subservient Jewish interests.”

Sunday, November 6, 2016

Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children / *** (2016)

“Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children” is not the sort of excursion that is alien to the behaviors of the eccentric Tim Burton, but unlike a plethora of the director’s recent output it sticks to you with a certain romanticized clarity, as if plucked from some untapped corner of his exhausted imagination. Some credit can be attributed to sharpness of the visuals and even the dexterity of the characterizations, sure, but the most certain of its qualities rests in the writing; based on a popular young adult novel by Ransom Riggs, here is a story tailor-made for the sensibilities of a dreamer, enriched by a consistency in the details that leave their viewers fascinated, shocked and at times enamored. Yet even enthusiasts of the Burton doctrine might find themselves bewildered enough in those realities to stand back in charmed perplexity – as much as they are likely to be thankful the opportunity to be once again swept up in a rewarding adventure, some will be inclined to attach footnotes. A filmmaker this gifted and this pointed in his observations is too precious a gift to be a slave to formula, and yet “Peregrine” represents a departure from that trend rather than the persistence of his individualism.

Tuesday, November 1, 2016

The Girl on the Train / ** (2016)

Every day she finds herself on a train staring intensely out the window, taking an interest in a set of lives that exist among a row of houses overlooking the tracks. They are the faces of people she knows little of, other than what her mind has imagined; one of them is a beautiful blond who wanders into the light full of joy and smiles, and the other is a lustful husband who devours every morsel of her beauty. To her those interactions represent a vicarious consolation of a life she once knew – an existence now etched into the recesses of a past apparently filled with tragedy and pathos. So obsessively does she correlate the two experiences, however, that inevitably they must bleed into one another, and in an opening narration there is a brief suggestion that their worlds are destined to end in fatalistic throes. Is that the pain of the past talking, or specific details she obsesses over? What is to come of a renewed interest from a nearby house in the same neighborhood, which may in fact be the source of her ongoing depression? The movie attempts to clarify the portrait by bouncing between three women as it attempts to frame them in a central story arc full of romance, deceit, mystery and uncertainty, yet it never dawns on any of them that they are participating in material that diminishes their value.

Sunday, October 30, 2016

Trick 'R Treat / *1/2 (2007)

The opening scene of “Trick ‘R Treat” shows a married couple arriving home at the end of a long Halloween celebration in the hopes of settling into less glamorous routines. The husband ventures upstairs and turns on pornography; the wife, eager to remove the decorations littering her front yard, begins the arduous process of dismantling elaborate displays of fake limbs and ghostly figures. A dialogue exchange acts as a shallow warning against the practice; he suggests blowing out the candle on the pumpkin by the gate violates the code of the holiday, which must be followed by fatal consequences. Shortly before she is murdered and disfigured by a figure hiding beneath bed sheets on the lawn, there is a moment where she stops to proclaim, without regret, that she “hates Halloween.” After a few short minutes into the bad movie she is trapped in, we can understand why; to be lost in the meandering chaos of a night like this with little to define the terror itself is a fate worse than any scares that might exist in the shadows. For the audience, the true horror is that anyone involved thinks they are pitching these curve balls for some great purpose.

Thursday, October 27, 2016

A Serbian Film / no star rating (2011)

There exists a hard, bitter audience for the likes of “A Serbian Film,” one of the most graphic depictions of human suffering I have ever seen committed to the screen. I am not among them. Perhaps that is because I was trained in the more tempered observations of film directors who found horror in the ability to make you jump without expectation, or shrink into your seat while the notes of the screenplay played your emotions through equal measures of silence and dread. Shocking brutality in itself was never enough – it was only the final outlet of the terror, a reason we were so terrified by the idea of evil villains capturing those who were running and screaming in the opposite direction. But for those who will look at Srdjan Spasojevic’s nihilistic plea against the pornography trade and find it engaging outside of the nightmarish cruelty, I salute them: not only do they have the stomachs to stare back at the frames with deadpan focus, they also have the distinction of being the byproduct of irreversible damage to the senses. For that, those individuals earn both my astonished bewilderment and my sincerest condolences.

Tuesday, October 25, 2016

Evil Dead II / ***1/2 (1987)

To think of Sam Raimi’s “Evil Dead II” as an elaborate exercise in gratuity is to undercut the reason it has so persistently endured in the hearts and minds of its audience, but to see it as some kind of perceptive satire would inspire connotations equally unreasonable. Both classifications suggest the thumbprint of a filmmaker who is either interested in deep irony or complete carelessness, neither of which can be substantiated; while the material certainly carries the aura of both, it is the underlying persistence of joy that dictates the direction of the narrative, a sense that it all must occur in a world so screwball that rationale has been displaced from forlorn considerations. While Raimi was certainly smart enough to fashion his endeavors in the mold of intellectual stimulation, that was never his primary interest; to him a movie camera was a tool to engage in pure celebration of his chosen genre, without all the seriousness or limitations that frequently come with it. And if blood was to splatter elaborately in a few incidental moments, what was the harm in that? Those early philosophies persist because they embody the sentiment that this can, realistically, be all in good fun.

Saturday, October 22, 2016

Unfriended / **1/2 (2014)

So rarely has a single genre of movies been as eager to adapt to the shifting dimensions of pop culture as that of horror. With each pass of time comes an eagerness to push the proverbial line of standard – some visual, others thematic – and inevitably the scope of the moviegoer is challenged to see beyond its routine. Oftentimes that requires the abandon of patience or personal judgment, especially when it comes to a concept that may be harrowing to confront. Those that are more interested in pressing on intellectual buttons are much more fun and refreshing to deal with: they understand the possibilities of novel techniques, at least if they are used to creative means. Think of both angles of that prospect as you move cautiously through the material of Leo Gabriadze’s “Unfriended,” a strange film about a vengeful spirit who comes back to haunt – and murder – a group of cyber-bullies who once claimed to be her friends. If one is to mention that the entire endeavor occurs on the computer screen of a teenage girl who flips between social media sites for 83 minutes, would you be annoyed by the concept, or intrigued by the method?

Wednesday, October 19, 2016

Funny Games / ***1/2 (1997)

The docile family that wanders out of civilization and into a wilderness where they are fated to be stalked and tortured is one of the more prevalent recurring themes of horror films in the modern age, but so few of them make the effort to pierce the membrane in order to revel in the warped ideologies of the villains. Michael Haneke’s “Funny Games,” a harrowing film, is of that latter sensibility. Audiences inclined to assume the most sensational possibilities are apt to descend into the director’s odyssey fully expecting the most perverse of geek shows, but what they will emerge with is far more rattling: the acknowledgment that seemingly ordinary people from a wealthy class system are capable of causing indescribable harm on others. We don’t just speak of physical harm in the conventional sense here, either; aside from bodily threats that generally lead somewhere unexpected and startling, the movie possesses intimidation, verbal cruelty, pranks, jokes and mind games that have all the characteristics of a sociopath’s behavior – they involve rules made only to satisfy the culprits, because that is in the nature of their game.

Sunday, October 16, 2016

"The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari" Revisited

“A reminder, and an example, of how today's filmmakers have forgotten about the overwhelming influence seductive imagery can have on an involving story.” – taken from the original Cinemaphile review of “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari”

Movie horror began not in the minds of Hitchcock or Castle but in the menacing gazes of early German cinema. Robert Wiene’s “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari,” usually accepted as the first prominent excursion of this distinction, was filmed and released in 1919 against the trajectory of its time, when those elusive few who actually saw films ought to have been far more enamored by the unsullied awe of moving images. What could have driven a single mind behind the camera to abandon the trajectory of his peers and dive headlong into a world so cynical and haunting, especially after many of his early films – now thought lost – contradicted that impulse? Having just been subjugated by more dominant European powers after the First World War, it was the country in which artists freely abandoned the beckoning of idealism and plunged head-first into the dark corners of the human psyche, effectively creating the tormented soul of German Expressionism. And while conventional wisdom suggests that such a compulsion inspired an uprising of dangerous political minds, it can also be credited with writing the language of the most celebrated of all modern film genres, a categorization of pictures made famous by the prospect of instigating fear the hearts of the audience.

Saturday, October 15, 2016

Opera / ***1/2 (1987)

At some point all serious spectators of horror films are destined to explore the trenches of Dario Argento’s catalog. As Italy’s most celebrated impresario of all things artistically macabre, he is a director who does not merely dabble within the traditions of a scary movie: he wraps them in the sort of decisive surrealism that often sits at the edge of our minds, struggling to overtake a thought as it is consumed by visions of blood. To those with morbid curiosity, a filmography that includes the likes of “Suspiria” and “Inferno” doesn’t amount to solitary experiences or even brief sensations. Like mind puzzles, they mean more when allowed to simmer over time instead of being forced through knee-jerk rationale. That can be troubling when one is confronted by the urge to plunge into the membrane of his complicated thinking, and more often than not that leaves more casual viewers with a dizzying conundrum: where in the world should they be expected to start with their education without hitting the wall of alienation? “Opera,” certainly one of the more accessible endeavors in his famous line, remains an ideal launch point for even the most pessimistic of cinematic wanderers.

Wednesday, October 12, 2016

Clown / 1/2* (2016)

One of the tragic realities of horror movies is rooted in the cause of sound moral judgment: a story in which very young children are destined to be slaughtered is rarely deserving of redemption. Varying degrees of that estimation have been seen on the big screen over the years, ranging from minor offenses (“Pet Semetary”) to more garish excursions (“Dinocroc”), but only those that move to the metronome of a compelling perspective can bring those sorts of risks back from the brink of despair. Jon Watts’ “Clown,” recently released after lying dormant in a studio vault for over two years, does something even more unforgivable: it goes well beyond sound psychology and hammers its point right to the spinal column of senseless and graphic cruelty. Thoroughly strange and shocking, the movie tells the story of a man who puts on an old clown costume and discovers, quite unfortunately, that it once belonged to a horrific demon known for devouring children, ultimately cursing him to the fate of possession. Meanwhile the movie exploits the nature of this idea by shamelessly dangling young victims in front of his ravenous face – the first of which is a 4-year old boy, who is so fascinated by the clown before him that he mistakenly attempts to make friends by barging through the front door while running buzz saws are set up the living room. Any further contemplation of this particular scene isn’t just grotesque, but vehemently depressing.

Monday, October 10, 2016

Exorcist II: The Heretic / * (1977)

In reflecting on the experience of moviegoers present for original screenings of “The Exorcist,” one usually forgets the root cause of their trauma: specifically, the fact that so much fear and violence was being orchestrated in the body of an innocent little girl in a tangible reality. Horror films up to the point of the early 70s typically played as open season for the lurid fantasies of filmmakers obsessed with the supernatural and the monstrous, but William Friedkin’s legendary opus represented the unhinged collision of those sentiments, a world in which the demonic energies could manifest in a place as plausible as any number of human stories of the era. As disturbingly convincing as the material played, however, perhaps that represented too great a challenge for the more perceptive directors of the time; against the trend that it would inevitably inspire, a great many years of crude (and usually unsuccessful) experiments followed in its massive shadow, often to the point of box office saturation. Among those failed lessons was one obligatory experiment: a direct sequel, helmed by the great John Boorman, which would document the ongoing struggles of young Regan as she attempted to make it through adolescence while keeping the memories of her possession in some sort of context.

Sunday, October 9, 2016

Madman / *1/2 (1981)

The unpleasant, dreary and humorless “Madman” is frequently cited among a handful of early 80s slashers as a genre standard, but it operates on one level that seems lost among its most loyal admirers: as a workshop for Darwinian selection. It was the great naturalist who first suggested the human race was the byproduct of centuries of inherent culling – that over time, a species was destined to conform to the environment it lived in while the inferior genetics would simply be forced to die out. One can argue a horror movie buried in the framework of the dead teenager standard always plays right into this theory, but rarely has it been so obvious, or indeed as unfortunate, as what filmmakers freely put on display here. The characters that populate the foreground of Joe Giannone’s film are suspiciously stupid, even by the measuring stick of his own premise. They barely function as humans, seeming lost in a haze of thoughts that are mechanical and uninformed. Their faces are frozen in confusion. They engage one another like they have no sense of individualism. Their dialogue is forced beyond comprehension, as if assembled by frequent trips down the greeting cards aisle of the Hallmark store. And that of course means they will be ill-prepared when they are required to react during a confrontation with a local legend, a deceased farmer who has returned to form to do away, I guess, with anyone that wanders into the woods he used to live in. Is he a maniac at all, or merely a soldier for evolution?

Saturday, October 8, 2016

Red Eye / *** (2005)

Wes Craven’s “Red Eye” begins with an abundance of strategic visual cues that recall the framework of some of the more sensational Hitchcock endeavors: shots of a stolen wallet, a crate of ice aboard a fisherman’s boat, urgent feet peddling through an airport terminal and news broadcasts about vague threats to homeland security. As isolated devices they seem far too fragmented to be congruent, but those well-versed in the language of movie thrillers know they must add up to something – in this case, a plot that must match urgency with underlying political intrigue. But what horrors are we inclined to contemplate, really, when the most threatening exchange occurs in a hotel lobby between an inexperienced clerk and two disgruntled guests? How are we to assume such menace is around the corner when the two leads, a pair of people who seem to meet incidentally at the terminal, share drinks in the bar and exchange stories that seem more like precursors to romantic interest? The genius of Craven’s long-standing affinity for such premises is that he knew exactly how to throw his audience off the scent of the danger, even though his most loyal viewers knew it must be inevitable. How many astute people consciously thought of ensuing violence, mind you, after Drew Barrymore answered a call from a wrong phone number at the beginning of “Scream?”

Friday, October 7, 2016

Cabin Fever / *** (2002)

Most directors of horror films are notoriously suspicious of human behavior. Eli Roth chuckles unsympathetically at their stupidity. That is not unfounded wisdom on any of those in the audience, who must approach a handful of his endeavors from a perspective that must accept the characters as casualties long before they are brought to elaborate slaughter. To see them is also to sense the impassive perspective of young adults in the 21st century, most of whom usually find themselves thrust into dire situations that would normally require years of therapy to recover from (assuming they were to stay alive long enough to book an appointment). Ironically, their director’s goals are much more singular than the contemplation of a reaction in a face: they are more an opportunity for his images to capture the ambitious dexterity of makeup and visual effects artists, many of them credited with some of the most brutal undertakings ever seen on a big screen. And yet one can’t help sense the delightful grinning going on behind the scenes, or the suspicion that crew members look at it all as a devious way to play the audience. There is pleasure in the violence, not any sense of serious deliberation. The approach might be admirable in a Sam Raimi sort of way if it also didn’t feel so utterly nihilistic.

Thursday, October 6, 2016

Candyman / ** (1992)

The opening shot of “Candyman” drips with the devious enthusiasm of a great ghost story. During a rather intricate voice-over that suggests ominous meaning for doubters of an urban legend, the sky behind the cityscape of Chicago is seen filling with swarms of bees – a jarring shadow cast over civilized procedure. They symbolize something foreboding: specifically the coming of an entity that once fell victim to them, a young black man at the end of the 19th century whose love affair with a white girl resulted in his merciless death at the hands of violent racists. Those are details that come to light, however, in an investigation nowhere near as compelling as the establishing visuals portray it; told in a style of filmmaking that doubles down as an investigative mystery, what we eventually find ourselves joining in on is an excursion through the lurid nightmares of the low end of the class system, a parable about how belief in the impossible allows it to become an applicable facet of fear and suffering in the modern world. And yet the movie never really has an understanding on what the real evil should be: the villainous visage standing in the shadows, or the social elements that have given him power over the meek and superstitious.

Wednesday, October 5, 2016

Hello Mary Lou: Prom Night II / * (1987)

Mary Lou isn’t some innocent teenage girl caught in the throngs of high school lust and deception: she’s a vixen preordained to be one of those homicidal sorts frequently seen in mainstream horror movies. Or at least that is what the early trajectory suggests in “Hello Mary Lou: Prom Night II,” until a disgruntled boyfriend tosses a lit stink bomb down the rafters and sets her on fire, forever cursing her to an afterlife without a prom queen’s crown. But as is the virtue of any living force destined to undo the happiness of others, goals so devious are only delayed instead of thwarted. And though it takes nearly 30 years of death to recharge her vengeful spirit, inevitably she will return to the sight of her demise and exact justice on others, whether they were participants in the tragedy or not. Audiences come to expect that sort of excursion ad nauseam in these sorts of pictures, but for a sequel that follows the footsteps of a rather ordinary teenage formula, what would have been the harm in changing it up a little? The scene of her death is so frustratingly passive that it creates rather persistent paradoxes: no one standing at the site of her demise seems eager to show the slightest interest in rescue, much less mere shock. Perhaps it would give too much credit to a teenage mind, but if I was killed in a fire and all of my classmates just stood by and watched me become a cinder, you can bet that every last one of them would be high priority on a revisit list the moment my ghost form returned to reality.

Tuesday, October 4, 2016

Prom Night / **1/2 (1980)

I am often amazed at the foolish tricks of absurdity that filmmakers play on their audiences, some of them so obvious that even lesser minds can see through their clichéd reasoning. Think for a moment about this predicament and then dial your mind back to “Prom Night,” one of the early slashers of the 1980s. Here is a movie about a group of kids who wander into an abandoned building, play a rather vindictive game of hide-and-go-seek and then spook the youngest girl into a situation that causes her accidental death. Surprised and dismayed about their situation, the remaining four swear an oath to never speak of their involvement in her fall from an upstairs window, and venture back into their ordinary lives in total silence. The camera briefly spies a shadow standing over the girl’s body to suggest a living eyewitness, and then abruptly advances six years to revisit the participants as they are preparing for their high school prom. Each of them receives an ominous phone call: a voice on the other end offers low growls of doom, and a hand is seen crossing their names off on a checklist. And somehow the audience is expected to believe that all four kids – some of them likable – could actually walk through life for this long without ever confessing their sins, or that their one witness has the patience to wait to a single moment so many years later to exact revenge on them.

Monday, October 3, 2016

The Entity / *** (1982)

The horror always arrives in rather dramatic waves. It is never predestined or planned, although isolation appears to be the catalyst for its shameless persistence. “The Entity” by Sidney J. Furie, one of a plethora of forgotten horror films from the early 80s, deals with this scenario on a narrative bedrock that defies mere convention: it tells the story of a woman – ordinary, single and straddled with three young children – who arrives home one evening and finds herself assaulted by an invisible presence in her bedroom. And it is no simple attack she undergoes, either: the nature of it is sexual, and the intensity of the incursion is such that she emerges from it shaken to the core, as shocked as she is violated. Others regard the incident with displaced uncertainty – how can anything happen if no one is in the room? – but here is a woman relatively sane by the measures of her peers, forcing added considerations. Maybe someone was in the room all along that simply waited in the shadows. Maybe the culprit rushed out of sight before witnesses could spot him. Maybe those strange incidents of doors slamming suggest a stalker is hard at work. Or maybe, just maybe, there is something transpiring in her world that defies mere convention, ultimately setting her up for the obligatory guffaws of friends and professionals who assume she is either making it up or acting out from some buried subconscious reasoning.

Sunday, October 2, 2016

Don't Breathe / *** (2016)

Theft of one’s property is a usually inspired by some external dilemma undermining the lives of the culprits. Seldom is the conviction spurred by mere greed or foolishness – it often comes from a place of desperation, an inkling to believe there is no way to escape a situation unless another’s money or assets can paint clearer paths through the confusion. Consider, for instance, what it means for young Rocky (Jane Levy) to belong to a trio of professional burglars in “Don’t Breathe” – though her team contains a token tough shot and a shy third wheel with a persistent crush on his female peer, all of her motives lead back to a necessity to escape a troubled family life filled with drugs, abusive stepfathers and prostitution. A ransacking of a stranger’s house is not so much an illegal act as it is an extreme measure that must lead to somewhere other than the cold mean streets of the Midwest, and though brief moments of self-awareness paint those deeds in ambiguity, there is no skepticism strong enough to keep her from that destiny. Surely a middle-income family in the suburbs can do without a few worldly possessions, after all, if it means an unlucky girl in the slums might use them to buy her way out of her own pathos.

Saturday, October 1, 2016

Halloween / *** (2007)

Masks are an integral device for the characters in Rob Zombie’s films, a tool that allows their dark agendas to manifest in the comfort of an elaborate masquerade. They seem to be, to them, a protection ward of sorts: to possess one implies that a victim may never be able to connect with the face of the person harming them, an essential function of holding power in a moment of violent aggression. A more revealing display would undermine the point of the pain they inflict. This is not elusive wisdom to any filmmaker that has ever overseen a vehicle involving murderous maniacs who wear such disguises, mind you, but almost always they were simply a ruse to keep audiences from discovering the identity (or at least the face, usually disfigured) of the culprit. But as we gradually move our way through the career of one of the more notable horror film impresarios of the 21st century, deeper reasons behind the implication are now at the forefront of discussion, and the line separating a dependable gimmick from its underlying psychology is gradually fading into the reveries of the past. Now it is hard to watch any film about such villains without instantly thinking of how thoroughly the façade unleashes a beast rather than hides it.

Wednesday, September 21, 2016

The Tree of Life / *** (2011)

Five years ago during a brief moment of inspiration, I sat down at a computer keyboard and pounded out the following words about Terrence Malick’s “The Tree of Life”: as ambitious as it is pretentious, the movie is as much a statement about the arrogance of its director as it is about one’s place in this world, which seems to be all about behaving childishly as a response to strict parenting rather than, you know, anything as profound as the images that surround it. That essay was never finished – among many others in the quietest writing period of my life – which may have been a blessing in some oblique manner. If hindsight is the tool that changes the way we look at things, then it became a valuable asset during a recent revisit of said opus, many moons after I had made a point never to see it again. Had I been wrong in my observations? Or just naïve? Perhaps the definition of my reality had given me cause to question what the director’s obligations were to his own thesis. For me, the broad context of the universe meant more than the idea of a mere kid moving in between attitude problems and parental persecution. But now I see that our little space is as relevant as we make it, and to deny the small things that make us who we are is to negate the point of asking the broader questions.

Saturday, September 17, 2016

Blair Witch / *** (2016)

And so once again I find myself confronted by the unnerving horrors of the Black Hill Forest, the site of a fable that haunts visitors who wander in for a glimpse of the evil hidden between trees. That legend is of course the notorious Blair Witch, a cursed demonic entity that rose to infamy in the whispers of superstitious townsfolk over two centuries and then gained added footing when three young filmmakers disappeared in search of her existence. It’s been over 20 years since those famous events transpired in the frames of a documentarian’s handheld cameras, but little has dissuaded the curiosity of outsiders – including the brother of one of those missing three, who comes of age and decides, perhaps justly, that there is still validity in wondering about the strange events. What happened to his sister all of those years ago? How come her footage was found, but not a trace of her or her two peers? Is she really dead, or does she remain in the woods as an eternal slave to the demonic energies of the witch? You’d think that nearly two decades worth of time would calm the turbulence of those suspicions, but I guess some malevolent spirits never lose their potency when they know cameras might be rolling.

Sunday, September 11, 2016

Kubo and the Two Strings / ***1/2 (2016)

One of the lost pleasures of the movies is going into a theater and gaining the sense that you have been absorbed in the far reaches of a new imagination. Just 16 years into a century of technical breakthroughs and creative dexterity, so few endeavors ever deal with concepts as novel as they are thorough. But “Kubo and the Two Strings,” a new stop-motion animated film from Laika Entertainment, is the antithesis of that belief, a film of nourishing visual insights and visionary storytelling that inspires as thoroughly as it dazzles. And that’s a surprise worth noting when one becomes aware of how taxing the endeavor must have been on its visual artists, who logged countless hours on building elaborate sets and crafting intricate details for a story set in medieval Japan. What inspired them to take the route they did, especially when the premise they were working with felt tailor-made for the styles of Hayo Miyazaki? Helmed by Travis Knight (who was among the skilled animators of “The Box Trolls” and “Coralline”), what pulsates on screen is nothing short of a remarkable artistic achievement, willfully empowered by clever facets in the edges and characters that have the adventurous spirit of some of the classic Disney heroes.

Tuesday, August 30, 2016

Watchmen / ***1/2 (2009)

A single character in “Watchmen” sits above the procedure of a superhero plot, and when he speaks the dialogue reflects a self-awareness that treads deeper waters than what is expected of these sorts of cinematic excursions. Known by his colleagues as Dr. Manhattan, he is the byproduct of an experiment that inadvertently liberated his spirit from the constraints of flesh and bone, and throughout the movie he is seen hovering through space like an ethereal body builder: sculpted, naked, trapped in a glow, never seeming to be more than an apparition in a fantasy version of reality. Perhaps it is his destiny to rise to the status of deities, or transcend the common knowledge of the race he was born from. But there is a wisdom in his observations that seems derived from more than the mere philosophies of Arthur C. Clarke or Stephen Hawking. When he speaks of walking across the surface of the sun or regarding the death of the human race as nothing to the context of a vast universe of possibilities, some part of us shrivels down to our bare defenses, sensing the painful truth of the statement. So elusive is the opportunity to extract such morsels from the fabric of a populist vehicle that they hit hard and swift, ultimately changing the trajectory of our embrace when most might have considered this little more than an ambitious and colorful – if pessimistic – story about masked crusaders attempting to function in a rather bleak human society.

Saturday, August 20, 2016

Florence Foster Jenkins / *** (2016)

The blessing of talent is a wonder undermined by self-doubt, while those created from a strong work ethic tend to discover the tenacity not often afforded to their peers. “Florence Foster Jenkins” is a movie about a woman who loves musical theater so dearly that she rises to notoriety because of her loyalty to the industry, far beyond the realization that she is also can be a rather bad singer. Friends and loved ones have shielded her from that reality out of an unconditional loyalty that stretches past the mere acceptance of great vocal range; everyone allowed in the room knows what they are hearing is tone-deaf meandering, and yet her impassioned confidence on stage silences critical ears and earns unanimous praise. But how does no one (at least up to a point) take a moment to be honest with the kind and gentle soul standing in front of the piano? Couldn’t she only benefit from the wisdom of a good ear instead of being crushed by it? Not all souls can easily escape the fragile nature of their history, and the context of Ms. Jenkin’s blissful ignorance is best summed up in a pair of scenes involving the reaction of a feisty female audience member, who in an early moment laughs hysterically at the performance and then in a later one silences countless others doing the same – “At least she up there singing her heart out!”

Monday, August 15, 2016

Ghostbusters / *** (2016)

Dialogue was one of the key strengths of Ivan Reitman’s immortal “Ghostbusters,” and when contrasted against special effects that were destined to become dated paradigms of the past it resisted the contextual erosion of most mainstream comedies. To hear the characters discuss their problems now is to sense two certainties: 1) the thorough skill of its writer, Harold Ramis, who was perceptive of human behavior beyond the momentary jabs of a punchline; and 2) the realization that the characters were responding to the material exactly as they needed to, regardless of how funny or whimsical their approach may not always appear. That’s because they were smart and had the foresight to explain themselves in the logical circles they routinely found themselves trapped in, where most would ordinarily be reduced to shrieks of terror or displaced from coherence. No one – least of all the Ghostbusters themselves – knew exactly how to regard a world where they were being consciously haunted by a series of bizarre specters, but to lose your sense of humor in the thick of all things weird might have been more damaging to one’s focus. No satisfactory resolution would have occurred with this sort of premise if those at the helm weren’t driving through it with a keen sense of awareness.

Sunday, July 31, 2016

Embrace of the Serpent / **** (2015)

A shaman stands fixed at the edge of a river embankment, his posture denoting tireless confidence. The forest behind him rests as a blur of deep vegetation and ominous noise – a towering portrait of natural order. Closed within that image is the soul of a man at war with the ideology of others; as the last known of a tribe thought slaughtered by missionaries, his skin is hardened by encounters with foreign tradesmen that seem interested only in exploiting the treasures of the Earth. Then a canoe carrying two passengers drifts in nearby, containing a pair of friends from different worlds (in his eyes, a civilization built on destruction). One is a former being of the forest who has abandoned the embrace of nature in favor of more sensational influences; the other, born in a world far beyond the trees, has wandered into it seeking adventure and discovery, no doubt with some level of misplaced elitism. But he has fallen ill amidst the search for a legendary item, and this lone warrior of the jungles – known as Karamakate – may possess the key to both its whereabouts and his own recovery from an ominous fever. But does the native have any sympathy to offer in this man’s hour of desperation, much less the basic desire to help?

Friday, July 22, 2016

Into the Abyss (2011)

There are two decisive moments towards the beginning of Werner Herzog’s “Into the Abyss” that left me in the inertia of sobering contemplation. The first involves an interview with a prison warden who oversees the comfort of death row inmates during their final minutes; as they are strapped to the table and prepared for lethal injections, his is the face that they will see last, looking down on them with only the offer of empathy in their transition to another plane. Some are grateful for the opportunity of a kind gesture in those moments, and in a confessional monologue he suggests a sense of complicity in their executions; these are human lives regardless of their misdeeds, and doing a job that contradicts those beliefs reduces the value of his soul. Herzog seems to echo these sentiments in the following scene when he comes face-to-face with Michael Perry, a death row inmate in Texas who is just eight days away from his own fatal punishment. “I don’t’ have to respect you or even like you,” he warns his interview subject. “But I don’t believe in capital punishment. I don’t believe you should be killed.”

Sunday, July 17, 2016

The Conjuring 2 / ***1/2 (2016)

When the mode of creating a horror film must involve some level of imitation, a director sometimes takes comfort in calling on the suggestion with shrewd wisdom. “The Conjuring 2” begins with a prologue in which the famous Warrens, Ed and Lorraine, are asked to descend upon a haunted dwelling to investigate the source of fright, previously held responsible for causing a disintegrated family to rush off in desperation during the middle of the night. Though it is never directly stated (it doesn’t need to be), dialogue and camera shots indicate that this site is the famous house in “The Amityville Horror,” and the fallout related to the exact same family that was featured in said film. Why did James Wan, the impassioned director of this ambitious series, go the route of creating such a connection? Perhaps it has just as much to do with setting a tone as it does emphasizing his own admiration. The original “Amityville” picture is frequently elevated as a benchmark in the rebirth of modern haunted house stories, but its most influential detail amounts to the realization that mere ghosts or malevolent spirits are nothing if there isn’t an instrument in the human world pushing their schemes. Like that film, here is a series that assumes a weakened soul is easily seduced by the evil in alternate plains of existence, no matter how strong an offense to it may become.

Friday, July 15, 2016

Jaws / **** (1975)

The key image in Steven Spielberg’s “Jaws” is not the first time we see the shark toss its head above water but one in which a little boy named Michael is seen settling into shock, just having witnessed a nearby swimmer swallowed by the mammoth predator. That moment, by all facets of an effective thriller, is the bridge that joins the terror unfolding to the relatability of it: suddenly the movie is no longer just about a horrifying danger lurking beneath the dark waters, it has become a working laboratory of personal fears projected into situations that could happen to us. A less farsighted movie would have ignored the inclusion of such a moment, or shamelessly tacked it into the crevice of a minor subplot. But even as a novice in the scene of Hollywood’s evolving machine Spielberg had the stimulus of a well-trained emotional conductor, and the plight of his young star – the son of the movie’s heroic center – was a shrewd maneuver that reverbed powerfully in the tense hearts of the audience. The clarity of an intention had seldom been so strong in the thick of so much ambiguous fright, and here is a man who made the moment seem as effortless as the delivery of a mere musical cue or establishing shot.

Tuesday, July 12, 2016

The Shallows / *** (2016)

“The Shallows” taps into that persistent fear of being in the ocean waters just as a ravenous shark swims nearby, and in doing so creates a space where predator and prey (in this case, a lone woman) engage in a bout of scuffs that is among one of the more taut excursions of recent thrillers. The early scenes work in disruption to that suspicion, mind you; colorful and optimistic, they seem edited together as if highlighting a travelogue of Caribbean memories. The heroine, an adventurous woman named Nancy (Blake Lively), engages the locals with enthusiastic formalities, although there are moments interlaced with pathos – she has come to this hidden beach isolated from family, who are still grieving the loss of her mother to terminal cancer. Why would she make suck a trek at such a pivotal time? It was a treasured vacation spot of her deceased parent, and surfing the turbulent blue waves is her device for grieving. And from the vantage point of the beach an important image emerges: a collection of rocks resting off shore that resembles, to Nancy’s eye, a pregnant woman about to give birth. “I don’t see it,” one of the natives chimes in upon her observation. Of course he feels that way; this is more a conduit to her deepest feelings, many of which will empower her sense of survival as the movie turns more menacing corners.

Monday, July 11, 2016

The Secret Life of Pets / ** (2016)

A dog finds happiness by merely being in the company of his owner. When that person walks out of the front door, it becomes a lonesome game of waiting until he or she comes back through. “The Secret Life of Pets,” a new cartoon about that mysterious slog between the departure and return of an owner, suggests there’s much more for canines to do in the meantime, not the least of which is get swept up into a city adventure where they are chased and hunted after they wander too far away from the comforts of their routine. Others – perhaps more busy with trivial matters – are inclined to join them out of loyalty. Sometimes that also includes encountering other animals during their venture, including those that have been discarded by owners; they thrive in the sewers of New York as a faction of four-legged gangsters, eager to recruit others in their scheme to rid the world of selfish and cruel pet owners. Much of this sounds rather exciting and whimsical when you paint a portrait in a movie review, but replace the dogs and cats with inanimate childhood objects and what you basically have is “Toy Story.”

Saturday, July 9, 2016

The Purge: Election Year / **1/2 (2016)

On the eve of my viewing of “The Purge: Election Year,” news headlines were flooded by reports of another police officer gunning down a black man during a traffic stop, reportedly because he was concealing a weapon. Cameras caught footage of the killing and a wave of protest swept over social circles, and with good reason: it was yet another in a growing list of offenses in which legal authorities had applied questionable judgment against a civilian of color (the second in the same week, even), and another in which the victim had been injured fatally. I bring this issue to mind not in any way to make light of it in a movie review, but essentially to highlight the relevance of present culture paradigms at the cinema. In a volatile genre like horror, where the degree of considerations usually amount to the depth of axe wounds or the consistency of a murderous rampage, it can be a rare thing for a modern scare-fest to build its foundation on current political ideologies. Eli Roth used it implicitly in “Hostel” at a time when anti-American sentiment was widespread in foreign countries, and James DeMonaco has echoed that call in a trilogy of films about government-supported holidays devoted to massacre. This third entry, certainly the most direct at connecting to the trend of the times, is the tipping point of a thesis that feels all too familiar in the world we live in – because we are living it with each new tragedy against the oppressed.

Monday, July 4, 2016

Independence Day: Resurgence / ** (2016)

Roland Emmerich was once a name synonymous with the loud and ambitious blockbuster trend of the late 90s, but in today’s movie climate his is a reputation diminished by a generation of technical wizards that have fully upstaged him. That prospect (not a minor consensus) weighs heavily as we descend head-first into the fatalistic “Independence Day: Resurgence,” a rather strange phenomenon of an endeavor: arriving exactly 20 years after its predecessor was a box office heavyweight, the wonder of a collective audience is interlaced with befuddlement, as if out of sync with the notion that this story was ever worthy of a follow-up. Emmerich has certainly made a career out of gargantuan catastrophes causing generational slaughter (his two most recent end-of-the-world vehicles, “The Day After Tomorrow” and “2012,” took that theme to the edge of catastrophe), but when it came to an Earth that faced off against an alien race that sought planetary destruction, where else could the concept go when the villain faced a clear defeat? Better yet, in a movie realm where the remaining population seemed to consist of just a few wisecracking cynics and emotionally scarred invalids, who would even want to go back?

Tuesday, June 28, 2016

Black Christmas / *** (1974)

Well before the homicidal tendencies of horror movie villains fell on ominous men wearing masks at Halloween or during summer camps at the lake, they were tucked away in the attic of a sorority house. Any aficionado of the slasher subgenre knows exactly what that phrase implies, but those less inclined to study the history have probably never even heard of Roy Moore’s notorious “Black Christmas.” Those are unfortunate sorts, many of whom have no doubt had their tastes molded by the trivial antics of lesser showmen in the crowded onslaught of scary movies. The irony of that proclamation is that the fanbase, usually quick to source benchmark origins for many of the ideas they hold dear, has been nowhere near as vocal in their respect of Moore’s film as many of the other key genre pictures from the past. Does that have to do with the continued obscurity of the endeavor, or the questionable reputation that slashers endure when held up against their more celebrated cousins? Whichever way you slice it, the resurgence of interest that came so long after its theatrical debut has been a muted affair, causing only ripples amongst those seeking knowledge of their favored field while others create more resounding echoes.

Sunday, June 26, 2016

The Reflecting Skin / ***1/2 (1990)

“The Reflecting Skin” begins with a scene of startling cruelty, in which three young boys mutilate a bullfrog on the road while a woman from town wanders nearby. Their goal: to use a slingshot on the amphibian and soak her dress in blood as she comes close to investigate. What exactly sets off this alarming “prank” is uncertain, but the events that follow offer startling clues that cast their behavior in a broader, more ominous light. Later, two of the boys taunt the third of the group, whose mother is dead; they make light of his misfortune until he bursts into tears. The mother of the primary observer is overheard in an obsessive compulsive rant that regards her own child as a disposable slob. Death (usually without explanation) begins to overtake their small community, and the arrival of a car carrying suspicious men – one who inappropriately caresses the side of one of the boy's faces – is viewed with stark foreshadowing by… well, no one other than the one child watching it happen. Slowly but surely the movie advances these cold realities into the most striking of tragedies, showing us the extremes of human misfortune (or mental illness, if you want to go that route) from eyes that may or may not be reliable in painting an accurate portrait of the truth. The movie speaks fervently of the “nightmare of childhood,” and perhaps a few long and painful minutes in the company of these characters are all one needs in reminding oneself of the luck we carry in living much simpler and joyous lives.

Thursday, June 23, 2016

Finding Dory / *** (2016)

Share in a conversation with a handful of loyal Pixar enthusiasts and you’ll discover very few commonalities between them. Over the course of twenty-odd years, the studio that mastered computer animation has given them a lifetime’s worth of diverse trophies to covet: yarns involving talking toys, busy bugs, cooking rats, machines that sense loneliness and even a few humans seeking adventure in the midst of personal grief, among others. Like the Disney name that oversees their output, they have become dependable facilitators of the most gentle of memories. But almost no consideration is complete without dealing with “Finding Nemo,” easily the most consistently celebrated film of their diverse lineup. On paper a mere story about the search for a clownfish stolen from the depths of the ocean is hardly that dynamic, but in execution it was a movie rich in skill and meaning; those who made it seemed as if they were weaving magic rather than just making yet another mainstream cartoon. Years marched by before its success translated to the most obligatory of marketing decisions – the promise of a sequel – but the thirst of the audience has scarcely diminished after the pass of thirteen years. Something about a reef full of delightful straight-shooters and gentle personalities instills a need in admirers for more, and the new “Finding Dory” is poised (at least at the box office) to quench that thirst.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)