And yet De Palma’s greatest mystery may in fact be the most obvious: a consistent student of the Hitchcock doctrine, his films were generally met with mixed receptions or tempered box office success. Did those notions contribute to his decision to abandon the studio system late in his career when it ought to have benefitted from his wisdom? The answer is what viewers will move towards during a journey that has him consider his endeavors in the hindsight of now, long after his career had its place in the creative tide. For some the conclusion, will be crudely juxtaposed against the affectionate illusions they still have of the medium; this was not a man whose aesthetic matched the ideals of those above him, and often they lead to the painful dismantling of reputations. For others, there will be something undeniably charming about a man who believed so strongly in his art, even when the merits of the end results were rarely in synch with any consensus. I myself remain conflicted in my lavish praise of De Palma’s strange tenure through the motion picture medium, but if all important creators strive to make films that mean something to an audience, few can deny his place in the annals of history.

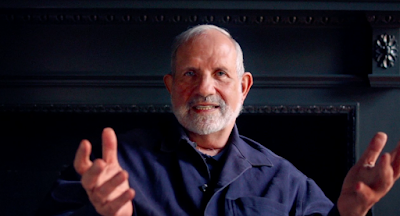

Even fewer, perhaps, will discuss the strange temperament that takes over on screen. Ever the controller of professional destinies and technical aesthetics, Brian comes off as a motor-mouth with questionable confidence during the time he shares with his interviewer, often using his hands to guide a thought process of answers while his eyes wander to the corners of the room. A lack of eye contact is regarded as one of the classic signs of social awkwardness, they say, but his raises more questions than answers – this, after all, was a man who shared camaraderie with the definitive filmmakers of the studio system during his early years, frequently passing around screenplays and advice with Spielberg, Scorsese, Coppola and Lucas. Is this a shell of the former De Palma we are sharing space with, or have his experiences undermined the approach he takes with those fascinated by him? The pattern adds gravitas to an arsenal of amusing anecdotes and fascinating back-stories, many of which are well-known in a movie circuit that has consistently analyzed and dissected his work.

The most fascinating of his films remains “Blow Out,” a grim thriller released in 1981 that was made in a flurry of controversy and arrived dead at the box office, but has since gone on to achieve the same sort of notoriety as Michael Powell’s “Peeping Tom” – as a landmark in the mechanical study of murderous tendencies. Though De Palma’s considerations consist mostly of the way things were during the first run, there is a revelatory quality in the way he paints the struggle with the studio, who began to look at his work as a nightmare for the censors after experiencing key successes early on. That underlying suggestion informed, perhaps, many of the experiences he would have in the films that followed, including “Scarface,” certainly his most well-known, and “Body Double,” frequently cited as his most misogynistic. But his was a stubborn and persistent craft that believed the material reflected the unending value system of the Hitchcock method – that details were made so not because they were exercises in personal prejudice, but because they put audiences in situations where they could freely contemplate where the boundaries belonged.

Usually the method was practiced in the clasp of significant production values – some of them gimmicky (the split screen device) and others resonating (the long-tracking shot). Almost always his prose relied on adapting techniques established by well-known sources, although it is not a detail he freely admits when he should (no mention, for instance, that almost all the key moments from “Dressed to Kill” were directly inspired by Dario Argento’s “The Bird with the Crystal Plumage,” including the famous murder using a straight razor inside an elevator). Is there shame that influences the omission of those details? I believe it has more to do with memory than strategy. Filmmakers of the modern era have never been innovators as much as they are re-inventors, and as one spends time in the company of such pictures they understand how ideas can cascade almost unconsciously. There is a great call-out he makes during a discussion about “The Untouchables,” in which he thanks “The Battleship Potemkin” for inventing his most profound moment: a shot of a baby carriage rolling down a flight of stairs during an ambitious shootout. Any person behind a movie camera that can take such a device and spin it into new gold not only earns the right to borrow, he has perfected the nature of cinematic homage.

This candid, insightful reflection is helmed by a pair of impassioned filmmakers: Noah Baumbach (who made the wonderful “The Squid and the Whale”) and Jake Paltrow (whose credits include mostly television endeavors). What fascinates them so much about their subject, I suspect, comes down to an underlying obsession with unanswered mysteries. Few knew exactly why De Palma left behind the trenches of the Hollywood machine, but one could wager educated guesses; if someone is only good as their last work, then the mishaps of “Snake Eyes” and “Mission to Mars” would have been enough to sour any prospect of endurance (although both of those movies were masterful compared to “The Black Dahlia,” easily his worst). But that’s only a fragment of a story created by an industry that has short attention spans and loves Cinderella stories. No, De Palma stayed away, primarily, because he was tired of higher influences attempting to box him in. Like Barry Levinson, he was never a man who cared much for the trends or trajectories of the moviemaking climate. Like John Carpenter, he was fiercely intuitive and saw beyond the scope of a mere budget or rating. And yes, like Hitchcock, he was enamored by the underbelly of the human condition to extents that put him at odds with censors.

The difference, perhaps, is that Alfred was far more persuasive and influential in moving outside those who would compromise his work, whereas De Palma frequently – by his own admission, no less – approached it too directly, which rarely bolds well in battles of power. Did it take a toll on his output? No more than it might have taken one on any number of directors who move so prolifically through their ambitious careers. Those that see an upsurge in later life are the exception rather than the trend. “De Palma” doesn’t attempt to justify or explain away the limitations that afflicted him over the course of four decades, nor does it have any significant opinion on how his filmography stands up against that of his more well-known peers. The goal of this encounter is to simply let its subject have a voice without filtering it through sugar-coated platitudes or passive acknowledgments. There is brutal honesty in these discussions – some of it familiar, other parts new, and all of it consistently gripping. And by the end, regardless of how one feels about any number of his pictures, there is no question that he was a man who made movies exactly the way he intended.

Written by DAVID KEYES

Documentary

(US); 2015; Not Rated; Running Time: 110 Minutes

Cast:

Brian De Palma: Himself

Produced by Noah Baumbach, Eli Bush, Mamie-Claire Cornelius, Eliel Ford, Jake Paltrow and Scott Rudin; Directed by Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow

No comments:

Post a Comment