Gaspar Noé’s “Irreversible” breathes the misery of its characters with the relentlessness of a voyeuristic conviction, invariably setting the audience up for a rather complex moral test: can you defend any film, artistic or not, that extends no restraint in the violence imposed on the living? Fifteen years after it pierced the membrane of our comforts, we remain distant from the possibility of consensus. Not one to shy away from the more volatile experiments of the modern cinema, I first shared in that journey with a handful of film enthusiasts who, too, could not initially process what they had seen. But in those early days of the movie’s notoriety I was also rattled by another noteworthy detail: a strange, throbbing murmur of a synth that loops over the critical second scene, during which a man’s skull is destroyed with a fire extinguisher. Is he the depraved individual responsible for the rape of another earlier that night? Is his victim now in a coma because of his deplorable actions? Do the responses of her friend and lover become necessary as vigilante impulses? Somehow my attempt to reason with the material was blurred further by this single chord of noise underlining the violence; it has a grizzly, chilling effect on the moment that haunts me even now, long after the senses have reconciled the horror and my mind searches for a thesis.

Showing posts with label 2002. Show all posts

Showing posts with label 2002. Show all posts

Thursday, October 26, 2017

Friday, October 7, 2016

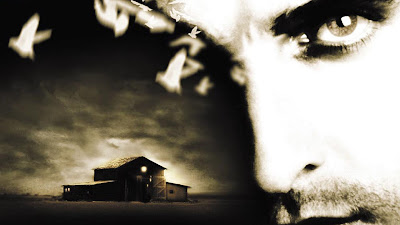

Cabin Fever / *** (2002)

Most directors of horror films are notoriously suspicious of human behavior. Eli Roth chuckles unsympathetically at their stupidity. That is not unfounded wisdom on any of those in the audience, who must approach a handful of his endeavors from a perspective that must accept the characters as casualties long before they are brought to elaborate slaughter. To see them is also to sense the impassive perspective of young adults in the 21st century, most of whom usually find themselves thrust into dire situations that would normally require years of therapy to recover from (assuming they were to stay alive long enough to book an appointment). Ironically, their director’s goals are much more singular than the contemplation of a reaction in a face: they are more an opportunity for his images to capture the ambitious dexterity of makeup and visual effects artists, many of them credited with some of the most brutal undertakings ever seen on a big screen. And yet one can’t help sense the delightful grinning going on behind the scenes, or the suspicion that crew members look at it all as a devious way to play the audience. There is pleasure in the violence, not any sense of serious deliberation. The approach might be admirable in a Sam Raimi sort of way if it also didn’t feel so utterly nihilistic.

Sunday, January 25, 2015

Blind Spot: Hitler's Secretary (2002)

In the winter of 1942, a young impressionable face came into the inner sphere of Adolf Hitler with simple aspirations of steady employment. Her name was Traudl Junge, and at age 22 all her worldly concerns came down to basic security, especially as Germany came under the rule of a regime that sought to, from an inside perspective, enhance the national workforce. A co-worker at the Chancellery had heard that the Fuhrer was seeking a private secretary and suggested that she apply for the position, and after excelling at a typing test she was whisked away into the wilderness along with a small cluster of other female applicants, where Hitler was privately obsessing over military orders in one of his many bunkers. She had never seen the dictator outside of political rallies or propaganda news reels, but at the center of her line of sight she discovered a courteous and mannered personality – far from the fiery oratorical genius that the public saw so regularly. In many ways, that was just as dangerous as it was disarming; Junge was the oldest child in a family without a male parental figure, and to her his almost fatherly sense of delicacy with the applicants was a refreshing quality, an aspect that seemed to fill a quiet void in her to be coddled like an affectionate child. It never dawned on her through the course of her employment that her boss led a life of dubious distinction, nor did she come to realize the depth of the atrocities he committed until long after the flames of war had dissipated.

Thursday, June 20, 2013

Auto Focus / *** (2002)

"A day without sex is a day wasted.” There’s a mantra that might have been the backbone to a college comedy, but here it becomes the ill-fated destiny shared between two unlikely friends in “Auto Focus,” a movie about the disintegration of actor Bob Crane and his conflicted friendship with a man who, for better or worse, probably was a conduit for many of the actor’s unhealthy off-screen obsessions. They exist not in Paul Schrader’s semi-biopic like life-long comrades but more as if mere acquaintances strung along through the same seedy life experiences for over a decade. They gaze at one another often and participate in what they feel is deep conversation. But they really never know one another, and are slaves to a lifestyle that requires only physical engagement, and only long enough to achieve climax.

Thursday, March 11, 2010

Downfall - **** (2002)

Friday, January 31, 2003

Chicago / ** (2002)

Showgirls kill their cheating lovers and claim to have never remembered it happening. Innocent and naive showbiz hopefuls shoot people who fail to deliver on the promise of a spotlight. Cellblock wardens supply inmates with all sorts of privileges and furnishings at a very steep price. Hotshot lawyers promise acquittal of any crime at an even steeper price. And crazy women convicts compete for press attention like rival celebrities drunk on media buzz, fearful of up-and-coming murderesses who could potentially outdo their own elaborate streaks of crime. Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to Chicago—the city that never shuts up.

Gangs of New York / ***1/2 (2002)

Martin Scorsese's "Gangs of New York" is a movie alive with greatness at several cylinders, a vibrant and challenging period drama that utilizes history, politics, intrigue and violence on the seams of a thoughtful narrative about the dark side of humanity. We've been taken to places like these often by Scorsese—stories that deal with characters who emerge from the shadows to take on the world around them—but seldom have they been structured with such painstaking precision or such compelling range. As you watch it unfold, you find yourself understanding exactly why the man behind the camera remains such a significant influence in modern cinema. This isn't just a movie you watch, after all, but one you experience.

Friday, January 17, 2003

The Best and Worst Films of 2002

The task of ranking the ten best movies of any year, most will gladly tell you, represents the most difficult challenge in the career of a movie journalist. As faithful messengers of the cinema, we spend 12 months slogging our way through countless major theatrical releases, struggling to uphold a degree of professionalism even during periods of bleak outlook, only to have it all thrown back into our face in the final weeks of the year before we have to start the process all over again.The effort is sheer madness on many levels and utterly tiresome on others, sometimes seeming rather pointless in the grand scheme of things. But then again, how else could us writers bring closure to the past before moving on into another pool of releases?

Friday, January 10, 2003

Adaptation. / ***1/2 (2002)

"Adaptation" is a film about the making of "Adaptation." Confused? Of course you are. But fear not, as this is exactly the kind of response that the movie expects you to have, if only for the first few minutes that it is on screen. It's about Charlie Kaufman, the writer of this movie and "Being John Malkovich," as he struggles to adapt a novel called "The Wild Orchid" into a screenplay (which is where this movie, the opening credits indicate, is adapted from). Failing miserably in his initial goal, he decides to shift the focus of his opus onto his own writing dilemma, putting himself into the story of "Adaptation" so that the literal result is the audience experiencing him during the writing of his own script. Get it?

Bowling for Columbine / ***1/2 (2002)

Ever since a group of teenagers descended the halls of a high school in Colorado on April 20, 1999, the subject of violence has been a painful and sometimes sluggish debate among the inhabitants of modern society. A legacy that initially founded the United States of America to begin with, violence has always been imbedded in the public's psyche, persisting even in times when the fear of it was much greater than the actual threat itself. But to what extent does that trait manifest into a living beast and consume its host? Does the media provide an easy outlet for it to take charge? And whose to say that any specific person or event is to cause for it unfolding? Columbine forced us to consider these difficult questions extensively, although we still aren't any closer to appropriate answers.

Far From Heaven / *** (2002)

It's amazing the lengths some have gone to in their praise of one of the year's most glossy disappointments. Todd Haynes' "Far From Heaven" is a biting and gorgeous social commentary saddled somewhere between dramatic brilliance and narrative miscalculation, struggling to keep a balance even when things start to spill drastically over the restriction. It is a very uneven effort that left me feeling incomplete on several levels, as if crucial points of justice weren't furnished completely or were simply abandoned just when things started to build up. Haynes assumes that the familiar plot conventions can be excused since they unfold in the 1950s, and in many regards he is brave for attempting the clash. But not everything takes off the way it should because the formula refuses to be entirely merged to the era. The script doesn't even treat the material like it belongs in this specific period; it's more like a series of afterthoughts that have merely been punched up for a very different kind of time warp.

Secretary / *1/2 (2002)

The experience of watching "Secretary" is perhaps more amusing than anything actually contained in the movie itself. What begins as an innocent exhibit of blank but intrigued stares quickly and effortlessly becomes a sea of twisted faces, confused eyes and disjointed smiles, exemplified by a crowd of film observers who no doubt feel like they've walked into some kind of sexual twilight zone without actually being told so. Just a quick glance at any person during the halfway point of the picture is enough to endure the on-screen torture, although just barely. And by the time its all over, the only thing that remains even remotely interesting in our minds is the fact that people can make their faces look so mutated.

Friday, December 27, 2002

Antwone Fisher / *** (2002)

The year has indeed been kind to actors trying their hand at film directing. Consider first Bill Paxton’s undertaking earlier this year with "Frailty," and then think of the latest of these efforts, Denzel Washington's "Antwone Fisher." Both labors of love for men who have seemed to possess a curiosity beyond the motion of the foreground, they have proven to be quick learners with each passing scene. Paxton’s first outing may be the best film of the year, but Washington’s, nonetheless effective, doesn’t quite make that mark. Here is a film that shows promise more than a power of payoff.

Evelyn / *** (2002)

What a sweet, gentle and feisty movie "Evelyn" is. And what an admirable little person its title heroine turns out to be, a redheaded Irish girl who isn't afraid to speak her mind and voice her concerns even if it means certain punishment from her overly-strict superiors. At the opening of the movie, which is based on true-life events in the early 1950s, the vivacious Evelyn Doyle (Sophie Vavasseur) and her two brothers are sent off into Irish orphanages following the abandonment of their flaky mother, their father, Desmond Doyle (Pierce Brosnan), seeing no need for the government to resort to such actions because of his own availability to raise them. Lifestyle and capability aside, however, he simply can't avoid the harsh reality of Irish law: that children are forbidden to live with just their fathers unless consent is given from the mother as well, a requirement that is challenged by the fact that dear old mom has seemingly disappeared from radar.

Max / **** (2002)

The moviegoer has come to expect almost anything from the filmmaker in these recent times, but it is doubtful one could have ever anticipated a movie that tackles the maniacal persona of Adolf Hitler on such an objective and fearless level. In Meyno Meyjes's "Max," which is less about the Max Rothman character than it is about the future German dictator, the impression is given that Hitler was not always the demonic figure we consider him to have been, but at one time simply an eccentric human being who was pushed beyond the borders of sanity and never able to find his way back. Historically, the movie probably follows accurately with what has always been said about him prior to World War II, but will any of that matter to the viewer? To discuss him in any context other than being evil is still quite risky; this is, after all, the most despicable living creation that existed during the 20th century.

My Big Fat Greek Wedding / **** (2002)

"My Big Fat Greek Wedding" is what you refer to as one of the great "grinning comedies" of our time, in which every scene and every character, no matter how silly or odd, leaves the viewer smiling from ear-to-ear in constant and utter delight. No doubt you've heard about the film by now, anyway; drawing audiences into the theaters week after week with few major attendance declines, the vehicle survives at the box office even most high profile releases fall by the wayside. It has even been said that movie might be a Best Picture contender for next year's Academy Awards. And if it is, what a great pleasure that would be! How often, after all, can you recall a PG-rated romance comedy that had enough exuberant charm and spirit to actually deserve a crack at the top prize?

The Pianist / **** (2002)

If Roman Polanski were not the same man who directed "Chinatown" and "Rosemary's Baby," he might never have been equipped enough to tell a story as difficult and poignant as that of "The Pianist." It's easy to pretend that a narrative of this emotional caliber simply requires a filmmaker with a distinctive knowledge of cinema, but the demand goes far beyond that; compassion and association are prerequisites as well. Not surprisingly, Polanski's greatest films explore parallel subjects—victimization, claustrophobia, and an underlying dogged hope that keeps the human spirit elevated to survival—and having mastered the themes before most modern directors even knew how to use a camera, he sort of becomes fated into the position, as if every significant product in his career has merely been a prelude to him forging this one. The fact that the story itself correlates with most of what went on in his own early life doesn't hurt matters, either.

Wednesday, December 18, 2002

The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers / **** (2002)

The opportunity to see history being made on the movie screen comes but once or twice a generation, and right here, right now, one of those rare events is happening with Peter Jackson's adaptation of the "Lord of the Rings" trilogy. Last winter saw the audience on its first rich excursion into Tolkien's Middle-Earth with "The Fellowship of the Ring," and now comes "The Two Towers," the second film in the series, which picks up exactly where its predecessor left off, diving headfirst into the material as if not a moment has gone by since we were last stranded in the realm of wizards, mortals, elves, dwarfs and hobbits. Much has happened since the adventure was halted 12 months ago—the first endeavor received 13 Academy Award nominations, grossed over half a billion dollars, and was even recently released as an extended cut on DVD—and yet the initial experience remains fresh in the mind, enduring even when other ambitious projects in that time frame have been completely forgotten (the latest "Star Wars," anyone?).

Brotherhood of the Wolf / **** (2002)

The French must know a lot more about cinema than we have ever given them credit for, particularly judging by the most recent products from their soils that have found an audience here across the Atlantic. The new millennium opened to the arrival of the rich and comedic "The Taste of Others," while the delightfully-vivid character study "Amelie" from last year provoked the curious eye almost as much as it exhilarated the viewer's spirit. The secret to the success of these two particular endeavors, and perhaps as it has always been with moviemaking in the country, is about stretching the cultural barriers beyond their own, embracing both French fundamentals as well as those of other civilizations to package an effort both rich and diverse in its techniques and legacies. It can even be argued that French movies aren't entirely French anymore, but Asian, American, Italian, British, and Indian as well.

Monday, December 2, 2002

The Santa Clause 2 / *** (2002)

At the beginning of "The Santa Clause 2," a plane with tracking systems begins picking up signs of disturbance towards the north pole, the lyrics of "Santa Claus is Coming to Town" riding the waves that the aircraft's crew are closely monitoring. Meanwhile, deep beneath the thick sheets of ice, Santa himself and all his little helpers rush against the clock to silence the source of this little rumpus, hopefully before any outside influences get too close to the source and discover their well-hidden village. It wouldn't be a terrible thing, we gather, if all the little workshops and townhouses for elves and little toy factory workers were discovered, but we can imagine the frustration of good ol' St. Nick—it's so hard, after all, to keep an effective assembly line going when you've got unwanted visitors threatening to disrupt your intricate pattern all the time.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)