A movie like this is almost unbearable without a coherent running dialogue. “The Miranda Murders” belongs primarily to that ever-so-volatile subgenre of found footage horror films, but must be prefaced with an even graver emphasis: all the footage functions as a reenactment of an actual killing spree that took place in California during the mid-80s. For those well-versed in serial killer psychology, the names will be familiar: Leonard Lake and Charles Ng were like blood brothers destined for infamy, linked by the nihilistic world view that innocent young women were meant to be abducted and then molded into submissive sex slaves for their own perverse pleasures, often in front of a camcorder. When they acted out or misbehaved, the punishment would be severe – sometimes violent, sometimes intimidating, always ending in their untimely demises. Now comes this strange concoction of a film that attempts to fill a great void: namely, what exactly transpired in those turbulent months between 1983 and 85 when they lured victims to their compound, filmed them in fearful protest and then disposed of their remains throughout the property? Though some of the actual footage of their exploits survives, the gaps were apparently intriguing enough to inspire Matthew Rosvally to interpret the unknown on old-fashioned analogue tape. The result is one of the most poorly realized ideas of recent memory.

Showing posts with label BIOGRAPHY. Show all posts

Showing posts with label BIOGRAPHY. Show all posts

Tuesday, April 21, 2020

Wednesday, July 31, 2019

Tenderness of the Wolves / **1/2 (1973)

You can deduce a lot about a madman by the way he is perceived by others. The conventional anecdotes are the staple of many retellings of their crimes. They were loners. They didn’t talk to anyone. Some thought of them as socially awkward. They never stood out, always seeming to disappear among the faces in crowds. And then there are the sorts whose sins come as a total surprise to onlookers who otherwise thought highly of the culprits. “No one expected a sweet man like him to murder those boys,” a resident in Houston, Texas once said of Dean Corll. “I considered him a friend, and I’m stunned by this all,” another spoke of John Wayne Gacy, shortly after his house was ransacked and 29 bodies were pulled from the crawlspace beneath. The more lurid and disturbing maniacs cast a long shadow of doubt amongst their peers, who would never assume something so heinous behind a set of charismatic eyes. That also means their crime sprees tend to be long and drawn out, no doubt since they provide few (if any) warnings signs. Yet as I watched “Tenderness of the Wolves,” a dramatic reenactment of the many crimes of Fritz Haarmann, I was struck by the almost cheerful ambivalence of his friends, lovers and onlookers as he routinely got away with the vicious killings of teenage runaways. Consider a scene, for example, when the notorious “Werewolf of Hannover” drops a slab of meat on the counter of a lady’s establishment, and she expresses glee at his arrival. He apparently doubles as a butcher, in addition to being a police informant. Others, however, find the texture of his delivery odd and off-putting (no one questions where it comes from, of course). But the restraint of curiosity belongs to a single pitch: what purpose is there to suspect a man so charismatic of engaging in anything so heinous? This is a movie that theorizes people are more content to look the other way on what is obvious than to deal with it directly.

Tuesday, February 19, 2019

Bohemian Rhapsody / *** (2018)

“Bohemian Rhapsody” is a biopic that is more resonant in theory than in practice, a study of Freddie Mercury that seems like it was filmed after its director and writer researched their subject over one brief afternoon on Wikipedia. What a shame it comes to this – that after years of false starts and changing casting decisions and ambitious goals, a film about one of the most profound entertainers of his time is barely motivated to offer the basic outline of his journey, much less a few precious insights. For a good while, it appears to be going somewhere: a series of early scenes feature the avid and gifted Mercury (played here with precision by Rami Malek) charm his way into a job as a college band’s lead singer, push them towards big gigs, master a distinct sense of showmanship on stage and even negotiate the band’s future in a record deal with significant creative control. Yet as the scenes pass and the camera peers into recording sessions to catch a glimpse of their intricate creative process, we begin to sense a distinct absence of a group dynamic. Their dramatic interest is curiously muted. Does that not, in itself, contradict the very nature of the Mercury persona, who moved as if guided by magic on stage while guarding over deep and meaningful relationships, including those with his bandmates, behind the scenes?

Thursday, October 11, 2018

BlacKkKlansman / **** (2018)

Ron Stallworth never perceived himself as having a “white voice,” but something about its candid inflection transcended the stereotype of black men speaking in the “jive” style of the early 70s. Spike Lee emphasizes this with unassuming assurance in the early scenes of “BlacKkKlansman,” showing us a man who is anchored by no particular sense of manner or distinction; he is simply an everyman seeking a place in the world, without much regard to whether he might be crippled or undermined by his ethnic background. Others are consciously aware of his presence, primarily, by the conditioning of their upbringing, but that’s of little surprise; he may be one of the only African Americans in a backwards Colorado town to ever walk into a police headquarters seeking a career in law enforcement. Some will come to regard him favorably after his capabilities are made known, while others will use their ignorance to blind them to his accomplishments. And though the film will tell the story of a man whose skill allowed him to successfully infiltrate the top ranks of the Ku Klux Klan, this is primarily about how injustice rebounds like an unpredictable pendulum, especially when it is controlled by men living in arrogance of their own privilege.

Wednesday, September 19, 2018

Unbroken: Path to Redemption / zero stars (2018)

“Unbroken: Path to Redemption” is a film that begins and ends with one fatal mistake: forgetting to tell its actors that they are accomplices in a cheap, patronizing melodrama. All the dramatic cues are there, and many of the faces convey an eagerness that is admirable, but every simpering scene of false sincerity moves to the rhythm of some shallow after-school special, where most of the conflict is resolved by broad strokes and nonsensical flash-forwards. For this, yet another aberration in a growing list of exercises by director Harold Cronk – and one that shamelessly follows a far better retelling of this story from only four years prior – the offense is greater: he takes a potentially meaningful discussion point about the traumatic aftermath of war veterans and reduces it to an arrogant demand for Christian unity. That some of it plays as convincing to these on-screen players indicates he has assembled a plausible ensemble to sell his message; that he doesn’t bother to supply them with a shred of intellectual context makes the film not only bad, but irresponsible and corrupt.

Monday, April 30, 2018

Last Days / ***1/2 (2005)

Three movies in Gus Van Sant’s filmography make up what is commonly referred to as his “death trilogy,” and like similar multi-picture endeavors by Ingmar Bergman and Lars von Trier they are linked less by story or characters and more by deep thematic echoes. But to describe the material in them as being just about “death” would be to simplify the nature at which they originate; while death itself awaits many of the important players, it is the journey towards it that stirs uncomfortably in the mind of their curious author. Consider the long and arduous walk towards nothing in “Gerry,” or the almost haunting silence preceding the chaos of the final hour of “Elephant.” Van Sant’s theory is not that some are meant to die young or tragically, but that they often do so because of a decay in stability brought on by lifelong alienations – many of them either self-imposed or clandestine. In these worlds, taking one final breath well before the mortal clock has wound down may just be a release from a routine that has already killed their goal to persevere.

Thursday, April 5, 2018

My Friend Dahmer / ***1/2 (2017)

I was a prepubescent teenage boy when the media first sounded the alarm against Jeffrey Dahmer, the mysterious serial killer from Milwaukee that stalked his community with almost silent precision. Ingrained by news headlines and evening bulletins as the Midwest cannibal, here was a shy, young and handsome man keeping horrendous secrets: over the course of his life he had murdered 17 young men – most of them gay – and then decimated their remains like an overzealous butcher. Many of those victims were never found, while others were discovered in mere pieces: a carved-out torso, several skulls and various other parts decorated the interiors of his apartment, where they served the purpose of feeding or arousing him. The concept of mass murder had hardly been a new commodity to contemplate in the public eye, but rarely had one’s methods so deeply penetrated the membrane of the mainstream, or done so with such austere consequences. Just as local towns in the Midwest heralded the aftermath with newfound caution, so was the gay community confronted by the great demon of negative stereotypes; it was as if Dahmer risked becoming a symbol against the lifestyle, a microcosm for disparaging perceptions running deeply through the moral majority.

Tuesday, February 6, 2018

Darkest Hour / ** (2017)

My first encounter with the versatile Gary Oldman originates from the age of 12, during a home viewing of “Bram Stoker’s Dracula,” where I first gazed at the eyes of a man with an unmistakable magnetism. His was the first figure to emerge on the screen, and somehow it had a disarming quality; a handsome and approachable face, full of plausible romantic longings, felt decidedly against the type we expected of a conventional villain. After he disappeared following the prologue, my mind raced with some sense of wonder – who was he? Could we come to see him as a negative force, as the story would ultimately require? And how could any woman, however fearful of his curse, find the strength to overcome his desirable advances, however dangerous? Only much later was it pointed out to me that the old man standing in his place during the film’s first act was the same Oldman, caked in heavy makeup to appear as a 300-year-old count in the shadows of Transylvanian architecture (different actors were cast all the time to play older versions of others, I figured). It was a testament to his ability that he was able to create a great enough illusion to fool even me, and over the years I have consciously followed him with the enthusiasm of a fanatic, curious as to what may come next in his life of relentless skin-shedding.

Wednesday, January 17, 2018

I, Tonya / ***1/2 (2017)

Tonya Harding wants people to know something they have refused to see – it’s never been her fault. No, not when she first took to the ice and treated her competitors with the same brash cruelty that her mother passed down to her on a constant basis. Not when she threw a vulgar tantrum in front of judges because they scored her low in one of her earliest skating competitions – essentially because she didn’t dress “appropriately.” And certainly not when her former friend and colleague Nancy Kerrigan was assaulted while training just a couple of months prior to the ’94 Winter Olympics, in an incident now famously known for the involvement of those closest to her circle. In whatever capacity you choose to accept the details – certain or otherwise – it’s never been a fair game to the poor misunderstood Ms. Harding. This despite her impeccable skill, her drive, her refusal to give up in the face of constant verbal and emotional abuse, and her history-making moves on ice that first captured her in the fickle public eye. No four words are uttered more frequently in “I, Tonya” than the dismissal of personal responsibility. But are they always mistaken, or is there some truth to the denial? Does she know any better? When the same phrase is repeated by nearly every important witness to her perplexing public history, it serves to emphasize the nature at which she was created. Here is a woman who was once loved, then vehemently hated, and now forever exists in that distant cesspit of pop culture pariahs where few hope to understand the reasons why people behave the way they do.

Monday, December 11, 2017

The Disaster Artist / ***1/2 (2017)

The first scene implicates the arc of the story: the underdogs versus the professionals. One of the former is seen in an environment he is clearly a novice in, acting out dramatic scenes in a classroom where stiff delivery suggests blatant disinterest. Greg (Dave Franco) says he wants to become a big movie star but is too caught up in the doubt of his material, and others look on with curious boredom as he mutters dialogue with robotic accuracy. Then emerges from the shadows of the back row a mysterious figure named Tommy (James Franco), who shows others that it is possible to be just as bad on the opposite end of enthusiasm – he reenacts a key emotional moment from “A Streetcar Named Desire” that is so painfully shrill that others cannot wait for the ordeal to end. Yet Greg, sensing his fearless nature, gravitates towards him with curious allure. He admires the audacity, the ability to be so caught up in a performance that everything else – including the judging gaze of the audience – is superfluous. Does it matter that he is untalented, tone-deaf or oblivious? Not in the least. Behind those eyes is a focus that most aspiring thespians would be envious of, regardless of what any of it might amount to.

Saturday, July 22, 2017

Christine / ***1/2 (2016)

The key observer in “Christine” is not the title character but her perceptive colleague, a woman named Jean whose distance would never be great enough to remain neutral from impending emotional traumas. She wanders passively in and out of newsroom conferences, sometimes engaged, sometimes quietly, but almost always with some facet of concern; among her peers is a female news anchor whose ambition is undermined by a crippling sense of self-doubt, and few others see the warning signs. Jean has known this instinctively since the early scenes, though there are few words exchanged that call attention to those realities. So paralyzing is her subject’s insecurity, in fact, that when there is an attempt to offer support, her kindness goes entirely unnoticed. But whether these details really did occur in the brief life of Christine Chubbuck is not so important as the conviction that puts them there. This is a movie about the prison that is depression, as experienced in lives removed from an awareness that might have changed an unspeakable outcome. And at the end of it all stands a kind young woman whose greatest crime was offering a gentle gesture when no others would, forever cursing her to the shadows of an eyewitness’ pain.

Friday, January 27, 2017

Funny Lady / **1/2 (1975)

The central relationship in Herbert Ross’ “Funny Lady” involves characters whose baggage has made them inconsolable mules: a gifted songwriter with no concept of stage management, and an experienced performer hardened by the weathering of failed marriages and declining artistic standards. They meet in an early scene that is destined to generate fireworks, but not the sort that necessarily constitutes positive distinctions. They argue, express mutual respect, discuss professional partnership, and even explode into aggressive verbal tangents, sometimes in that order. There are claims of dislike that infuse their interactions, yet they continue to find reasons to be around one another. Does the aggravation inspire them? Or are they feeding off the blatant honesty of the moment, perhaps because it is a luxury rarely afforded to them? They say that damaged souls with a quick tongue have a loyalty to those who spit back the same venom; because they understand the context of the words, a respect persists beyond the outlandish tirades. Theirs is a connection so strangely alluring that it gives the film an edge rarely seen – not even in “Funny Girl,” its popular predecessor, where the only significant relationship the female lead had was the one she shared with the audience.

Saturday, January 21, 2017

Funny Girl / *** (1968)

On the cusp of what seems to be turning into the silent death for movie personality, great stars of the past century have entered a stasis in the memory as images of a lost idealism. One of those in particular – the face of Barbra Streisand – embodies the spirit of the most important of filmmaking eras, when conventional beauty was redefined by those whose gifts were as monumental as their artistic endeavors. A divisive figure who rose from the cinders of old Hollywood glamour, found her presence during the age of feminists and endured beyond the inert populism that would attempt to silence her great aspirations, few entertainers of the past hundred years match the depth of her contributions. To consider those achievements now is to be swept up into the awe she has created in the hearts of her most loyal admirers, many of whom have come to regard her legend as pervasive even among her most accomplished peers. On a chance occasion this last August she and I finally came face-to-face during one of her rare concert tours, which culminated in an even more resonant realization: midway through her 70s there is a sense that no other living performer is as motivated to spread richness among members of the audience, even when they might not be as cognizant of the realization.

Tuesday, December 20, 2016

Honest Man: The Life of R. Budd Dwyer (2010)

The first time any young journalist hears the name R. Budd Dwyer it usually occurs during introductory reporting curriculums, when the discussion shifts from writing styles and plunges into the troubled waters of ethics. Once thought to be the leading point of an argument about appropriate newsroom conduct, his very public suicide in front of television cameras has come to rest in the margins of a convoluted history in media decency, especially in the wake of a post-9/11 world of bombings, massacres and civilian beheadings. But it persists, no doubt, because there remains almost no similar conduct for people to compare it to; as such, his is a situation frozen in the shocking embrace of controversy, and a constant source of ambiguous political arguments that would like to erase his strange existence from memory. Shameless voyeurs, however, have preserved his notoriety even more than those fascinated by the puzzling circumstances leading to that tragic day, and easy is the opportunity to search the internet for those final moments, relentlessly plastered all over video feeds. Some may initially wonder if “Honest Man,” a documentary about his troubled political career, would even have been relevant if his last act had not continued to reverberate with perverse allure. Is there anyone left that cares more about the context of that moment than the disquieting inevitability of his lifeless body slumping down in front of a room full of cameras?

Monday, December 5, 2016

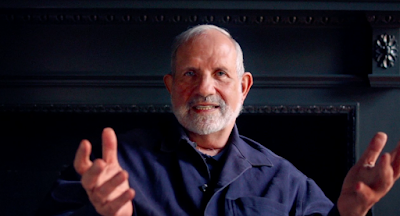

De Palma (2015)

Like most 20th century directors working in the wake of the golden era, Brian De Palma’s sense of craft was not so much a divine creation as it was an enacting of the rich experiments of Alfred Hitchcock. Such wisdom is cursory to any serious record of modern filmmaking, and “De Palma” – the new documentary about his notorious career – begins with a discussion about “Vertigo,” the most direct of his Hollywood allegories. “What he was doing,” De Palma describes, “was creating these romantic images and then killing them off. And that’s what we as directors do all the time.” It is a precious morsel countless others have discussed in unison with their laborious practices, and certainly Hitchcock’s most treasured film is regarded as autobiographical for most, but do his lessons reverberate as consistently as they should? The famed creator of “Dressed to Kill” doesn’t believe so; in a two-hour sit-down that involves crawling through his catalog one picture at a time, the most persistent of points is how Alfred’s shadow has been so dimly cast by those working within his traditions, unless you happen to be him. Perhaps that says more about the subject at hand than those who have freely abandoned the structure of their important ancestors, but far be it from any fascinated observer to interrupt the lines of thinking of one of the more popular creators of the medium.

Saturday, August 20, 2016

Florence Foster Jenkins / *** (2016)

The blessing of talent is a wonder undermined by self-doubt, while those created from a strong work ethic tend to discover the tenacity not often afforded to their peers. “Florence Foster Jenkins” is a movie about a woman who loves musical theater so dearly that she rises to notoriety because of her loyalty to the industry, far beyond the realization that she is also can be a rather bad singer. Friends and loved ones have shielded her from that reality out of an unconditional loyalty that stretches past the mere acceptance of great vocal range; everyone allowed in the room knows what they are hearing is tone-deaf meandering, and yet her impassioned confidence on stage silences critical ears and earns unanimous praise. But how does no one (at least up to a point) take a moment to be honest with the kind and gentle soul standing in front of the piano? Couldn’t she only benefit from the wisdom of a good ear instead of being crushed by it? Not all souls can easily escape the fragile nature of their history, and the context of Ms. Jenkin’s blissful ignorance is best summed up in a pair of scenes involving the reaction of a feisty female audience member, who in an early moment laughs hysterically at the performance and then in a later one silences countless others doing the same – “At least she up there singing her heart out!”

Friday, September 18, 2015

The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser / ***1/2 (1974)

Minds do not always harvest congenial reactions when they are exposed to foreign realities, especially when they are so grossly detached from them for lengthy tenures. That is one of many significant functions of “The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser,” Werner Herzog’s stirring fable about a young German who mysteriously wandered into Nuremberg square on a warm day in 1828, and right into the clutches of a culture that would leave him in the throes of permanent alienation. His origins are of inexplicable depth, and yet help to emphasize the challenge of exploring such strange surroundings. For the first two decades of his life he was chained to the wall of a dungeon in an undisclosed area, and was never permitted to learn or experience anything beyond the comfort of a bed made of hay. He could barely walk, speak nothing coherent and had no knowledge of simple human interaction. Where did he come from? How did he escape? As perplexing as his arrival – and subsequent integration – came to be, perhaps they were just minor exercises compared to the nature of his ambiguous upbringing, which seemed to cast its own dubious shadow on his brief time in civilization before it ended just as mysteriously as it began.

Friday, July 3, 2015

54: The Director's Cut / *** (2015)

A modest act of vision can instigate hard-fought wars within the film industry, and such battles are seldom resolved in the favor of directors. One of the more legendary discussion points in that scenario is Mark Christopher, whose “54” – a long-forgotten relic from the summer of 1998 – arrived on screen in a flurry of hype, and then left with scarcely a notice beyond faded party-goers. It had been pushed by the Miramax promotion machine as the definitive expose on the controversial legend of Studio 54, but what wound up showing in theaters was actually a watered down rendition of Christopher’s original picture, which had been butchered significantly and then refilled with a variety of reshot footage (reportedly, up to 30 minutes of alternate scenes). The reason? According to the film’s distraught creator, the studio wanted less drug use and homoeroticism than what they were given, and demanded more visual excess (not to mention a much more conclusive ending). Only years later did the tribulations of it all come to our full awareness, further perplexing the matter: if the released product was such a financial and critical failure, what was the harm in releasing the original version in some other format after the fact?

Monday, April 27, 2015

Foxcatcher / ***1/2 (2014)

A single question in the early moments of “Foxcatcher” serves to frame the impending experience of characters: “what do you hope to achieve?” For three men brought together by love of a competitive sport, their initiatives are stirred from emotional currents. Mark (Channing Tatum) is an Olympic gold medalist whose prestige from one of the “lesser” competitive events has not done much to curb his sense of isolation. His older brother, the more family-oriented David (Mark Ruffalo), keeps watchful eyes on his loner of a sibling all while observing his success with some sense of humility. In between them stands John du Pont (Steve Carell), heir to the du Pont fortune, whose love and dedication to the sport of wrestling has made him somewhat of a radical enthusiast – to what end, one wonders with cautious curiosity. Is it simply the love of it all (or the rigorous training that comes with it) that makes him such an avid champion of competitive training? And how much of that comes from an upbringing that reduced him to a background distraction on part of a mother who adored her riding horses more than doting on her own son? Each of these individuals is out to prove something to someone – to others, themselves, or to family members – and in almost all of those examples their obsessions only mask an insecurity that has the capacity to bring them to dangerous epilogues.

Monday, July 28, 2014

12 Years a Slave / **** (2013)

Steve McQueen’s stark, powerful “12 Years a Slave” leaps far beyond the notion of basic film composition and penetrates to the core of the human condition, at a time when the acts of a people left a stain on our civilization from which there could be no return. To see it – and indeed, to experience it – is to be part of one of the most haunting encounters we will ever have with a movie screen. Based on a prevailing memoir of one man’s perseverance during the years of American slavery, the film is the embodiment of historical resonance, and McQueen doesn’t so much direct a picture as he allows his mind to be a vessel for unflinching candor while a camera bears witness. Here is an endeavor so brutal, so honest and stirring, that it inspires a collective pause akin to what “Schindler’s List” did for the subject of the Holocaust.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)