And yet for nearly no exclusive reason, here is a movie that today rarely gets mentioned as a source of importance in film heritage. Nor does its director, Victor Sjöström’s, get showered in the level of praise that other important silent film directors, like Fritz Lang and F.W. Murnau, would witness in their time. The reluctance, perhaps, exists more in context with the grave subject matter in an era of artistic optimism, when audiences accepted moving pictures as a gateway into possibility as opposed to conduits of our deepest and darkest fears. The Germans, on the other hand, had already embraced the formative nature of dark and twisted themes with “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” in 1919, and awaited the eventual arrival of other important works in their era of Germanic Expressionism, such as “Nosferatu” and “The Golem.” For Sweden, “The Phantom Carriage” represented a stark contrast to the material they were already embracing in the medium, and a shadow of uncertainty would loom over the film in its earliest years as audiences struggled with the notion of embracing something so clearly in a new frame of psychological reflection.

It is perhaps solely through Bergman’s presence as a master in international cinema that the movie finds its deserved credit as the first undertaking of its kind: a horror movie with thorough human implications as opposed to just a succession of fearsome images. Not that there is any lack of supply in reference to visuals, however; shot by the prominent Swedish cinematographer J. Julius on the grounds of the legendary “Filmstaden” (the famous movie studio built in the town of Råsunda), the film creates an alarming depth through camera angles and far-reaching set design that was above the benchmark of the silent era (sans D.W. Griffith, whose “Birth of a Nation” and “Intolerance” far exceeded even that prospect). The spaces created are amplified even more so by an impeccable sense of lighting, which seems to originate from minor sources, like a single candle, but somehow illuminate many surfaces while emphasizing conspicuous shadows. This effect must have been overwhelming in an era where moving targets were single points of light on a canvas devoured by static backgrounds.

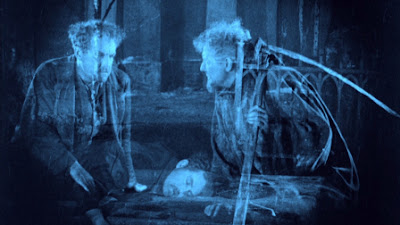

The images that are well known among film societies and movie buffs clearly earn their reputation. The carriage itself, a device of great importance that carries dead souls from reality to an uncertain afterlife, is crude and jarring in the way it sticks out against the foggy light of nighttime. The horse that carries it is seen in blurs, perhaps to hide the notion that its deathly ribcage is actually just lines of paint on a steed. In more localized scenes, it and the carriage pass through space with an effect of translucency that must have been difficult to achieve even for a clever director. Double and triple exposures are clearly at work to accomplish this impression, but the degree to which the result succeeds is disquieting. In some scenes, when figures from the ghostly apparatus are required to walk through scenes containing moving pieces or characters, they are staged exactly in the way necessary to perpetuate the illusion of dimension, and we are left with a sense of eerie wonder. Meanwhile, interior shots are tinted in warm hues while exteriors are done in deep blues, creating the measured feeling of climate that the movie seems to use as a method of emotional tone.

The story is equally potent. The movie opens on a new year’s eve, and a dying sister from the Salvation Army named Edit (Astrid Holm) summons the presence of a man she has looked after named David (Sjöström), whose life has been a series of unlawful run-ins and destructive tendencies. He is a drunk lacking clear direction and desire, and his loving family quickly loses patience; his wife (Hilda Borgström) has already uprooted herself and their two children once, and threatens to do so again if his vicious cycle runs the risk of endangering their safety. Such routines are plagued notably by the presence of mindless tag-alongs, all of whom interact with the man in a joyous manner but are warned by others, quite succinctly, of the negative nature Mr. Holm will inflict upon his peers should they stick around long enough for the full reveal.

Simultaneous to these notions, an acquaintance of David’s named Georges (Tore Svennberg) eludes to an elaborate fate that exists between two worlds known as “Death’s Carriage,” and foretells of a grisly fate: the first person to die at the stroke of midnight on New Year’s Eve will be cursed to being the carriage’s grim coachman for an entire year, collecting all the dead along the way. A haunting example is displayed early on, when the carriage’s driver arrives at the steps of a mansion and walks through doors and walls into a parlor containing a suicide victim, who has taken his life with a pistol. David perceives this story as little more than a fairy tale, however, and continues to engage in scuffles with local ruffians. And on the night of Edit being on her deathbed, he ignores her summoning and is brought to fisticuffs with two lowly drunks who attack him brutally, and all of it commences quite near the stroke of midnight going into the next year.

If the first half of the film is a coarse display of the grim implications set forth by the presence of a deathly chariot, then the second act is more a chronicle of David’s life set in flashbacks. The material is nearly assaulting in what it uncovers through such narrative prodding, sparing us all the elaborate polish that would become the padding in the glitzy trajectory set forth by the mainstream Hollywood of the 20s and 30s. This is especially obvious in the way Sjöström shoots key characters, such as Mrs. Holm, whose aged presence is matched by a noticeable slouch in posture, and a face filled with buried notions of fear and regret. Others, like Edit, are conveyed more warmly to emphasize the optimistic nature of their presence, and when the movie requires souls of two opposing emotions to interact, their dichotomous nature creates an uneasy tone that is felt by the audience with scarcely a word or outburst.

There are certain primitive approaches in other bits that undermine the eventual goal, perhaps – a prison scene in which the David character is forced to interact with his younger brother is quite preposterous in the way it delivers overly idealistic dialogue, and a crucial twist in the final act, while spotlighting the movie’s goal of its main character seeking redemption, nonetheless feels jarring against the presence of Death’s chariot, which is too powerful to exist as a mere plot device in any movie, much less this one. But these diminutive failures are not synonymous with a perspective of miscalculation or laziness – rather, they exist as indicators of a director’s persistent struggle to comprehend and master the intricate nature of film language in a time when film was still too primitive to reveal its true scope. Just as stories must adapt to their mediums, so did the early film directors have to assimilate to the sense of conveying their endeavors without a net to catch them in obligatory blunders.

Like most of the gifted moviemakers, Victor Sjöström was possessed not just by ideas but also an insatiable drive in the creation of motion pictures, and his neurosis with detail made him somewhat of a control freak to his peers, many of whom dismissed his drive as an act of lunacy in a time when the cinema required architects more than cameramen. Not merely content to push actors or cinematographers to his expectation, furthermore, he also was the star in several of his own films, including this one. We can imagine Bergman being as equally moved by the emotional presence of his screen persona here as he was by the striking style and delivery of the picture, otherwise he might not have been so motivated to star his mentor in two of his own movies: “To Joy” (1950) and “Wild Strawberries” (1958). The mannered display of his later performances is incomparable to the unrestrained thrust of his early work, no doubt because of the overzealous theatrical quality required of actors who must work in the absence of sound and dialogue. But in each instance, what these performances illustrate is an undeniable passion for the craft both in front of and behind the camera, clearly in the hands of someone who was weathered by the medium’s evolving traditions over the course of several decades. “The Phantom Carriage” is not so much a whole film as it is a filmed collection of ideas, but the manner and enthusiasm to which they are realized is arresting, and hypnotic.

Written by DAVID KEYES

"Lessons in Criterion" is a weekly series of essays devoted to exploring the films released within the Criterion Collection on Blu Ray and DVD. Noted for their notoriety or importance in their effect on the evolution of cinema, these films are not rated on the 4-star scale in order to preserve the intent of the work, which exist to promote discussion and inspire thought on their relevance in the medium. More information on this and other titles can be found at Criterion.com.

"The Phantom Carriage" is the third article in this series.

"The Phantom Carriage" is the third article in this series.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment